The NDP’s critic for Indigenous issues says it’s time to redesign Canada’s century-old coat of arms, which has emblems honouring the country’s English, French, Irish and Scottish heritage, to include symbols representing First Nations, Inuit and Métis.

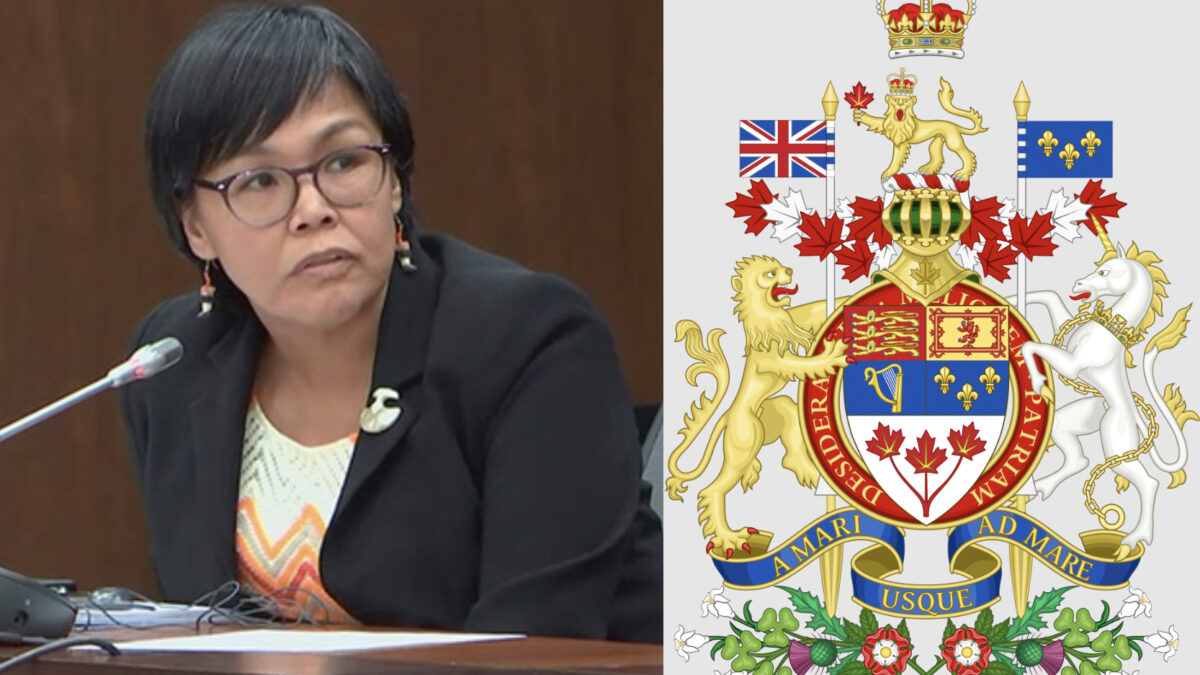

And Nunavut MP Lori Idlout says the country should also rewrite the motto that appears on the coat of arms, expanding “From Sea to Sea”to encompass the Arctic Ocean, as well.

The coat of arms turned 100 on Nov. 21. The main symbols on the emblem represent the groups considered the “founding” European people when the Dominion of Canada was established in 1867.

Idlout and others say there is a glaring lack of representation on Canada’s heraldic symbol of those who were on the land since antiquity.

“I think it is important that there is First Nations, Métis and Inuit representation in it,” Idlout told Capital Current. “I think it’s about time.”

Idlout said if the coat of arms were to be changed, it must be done in consultation and collaboration with Indigenous peoples.

Idlout also supports adopting a new official motto — which appears in Latin on a scroll beneath the central shield of the coat of arms — to better reflect the true geographic scope of Canada. The current motto – A mari usque ad mare in Latin – should be reworded to reference the Arctic Ocean for northern representation, Idlout said.

“Canada is a huge country and with my riding representing the largest part of Canada. I think our oceans must be recognized, as well,” she said.

In 1921, King George V proclaimed the coat of arms to replace a previous crest made up of provincial coats of arms.

The coat of arms features three royal lions representing England, a royal lion and unicorn for Scotland, a harp for Ireland and fleurs-de-lis for France, according to the Government of Canada website. Floral emblems of the four countries carpet the bottom of the coat, which is one of nine official symbols of Canada, including Maple Leaf flag, the beaver and the national anthem.

“I grew up in a colonial education system so I was taught to see it as a symbol of Canada and how important it is to respect it,” Idlout said of the coat of arms. “I’ve always thought it was an important symbol of who we are and what we stand for.”

Idlout said as she grew up and recognized the effects of colonialism in her education, she began to rethink how she feels about these symbols as a proud Inuk.

She added that adding Indigenous representation to the coat of arms would not only constitute an act of reconciliation, it would also acknowledge Indigenous ancestors’ place on the land long before European settlers came and lent the symbols of their homelands to Canada’s heraldic shield.

Toronto resident and history buff Philip Stern remembers seeing the coat of arms on mailboxes and schools in Montreal throughout his childhood. He said the emblem reminds him of Expo 67 — the world’s fair held in Montreal in 1967 — when he was eight years old, a time when a renewed vision of the Canadian identity was taking shape.

“I think we had subsequently become much more comfortable in our Canadianness and in our distinction from the Americans,” said Stern. “Of course this emblem certainly highlights that in a highly colonial — an extremely colonial — inspired emblem.”

“I think it is important that there is First Nations, Métis and Inuit representation (on the coat of arms). I think it’s about time.”

LORI IDLOUT, Nunavut MP and NDP critic for Indigenous issues

In 2017, Stern authored an article in the Ottawa Citizen paying tribute to the coat of arms but arguing that it should be updated to reflect Canada’s Indigenous Peoples while retaining its artistic quality.

The column, Stern recalled, was prompted after he’d spotted a black garment bag bearing the Canadian coat of arms while travelling through Chicago’s airport.

“It certainly gave me a jolt of patriotism and a jolt of connection because I had a fondness of this symbol for quite a time,” Stern said. “It’s just one of the most beautiful symbols to my eye that is currently in use.”

While he highlighted the lack of Indigenous representation in the coat of arms in 2017, Stern said the omission is “very glaring now” — near the end of 2021, after Canada’s first National Day of Truth and Reconciliation on Sept. 30.

“I recognize just how out of step it is with truth and reconciliation,” said Stern.

Nearly two years after that column was published, former Winnipeg Centre MP Robert-Falcon Ouellette — an Indigenous member of the Liberal caucus during Prime Minister Justin Trudeaus first term in government — presented a petition to the House of Commons with more than 550 signatures. It called on his own government to revise the coat of arms so Indigenous Peoples are recognized as co-founders of Canada.

Ouellette, who was defeated in the 2019 election, still supports the idea, saying the coat of arms should represent all Canadians and distinguish Canada as its own nation.

“I think for Canada to be our own country, it obviously has to have our own symbols, which are well represented within that coat of arms,” Ouellette said. “I think that should involve discussions with Indigenous people, newcomers, people from all walks of life about what those symbols are exactly – what unites us as Canadians.”

Ouellette, who is from Red Pheasant Cree Nation in Saskatchewan, added: “What would speak to everyone, that if someone sees the coat of arms, they go, ‘That is us; that talks to me.’ ”

The government’s reply to the petition in 2019 was that the coat of arms features elements of Canadian identity and heritage as they were perceived in the early 20th century. They also said the sprig of three maple leaves on display at the bottom of the shield represents the peoples of Canada – the English and French settlers, as well as Indigenous people.

“Revising the coat of arms of Canada to include representation of the Indigenous peoples as co-founders of Canada would require meaningful engagement with Indigenous peoples, through an extensive process overseen by the Canadian Heraldic Authority, with the continued support of the government,” said the formal reply to the petition.

Heraldic authority combines tradition with modernity

The Canadian Heraldic Authority said it is ready to act on any requests from the current government to review the coat of arms, said Bruce Patterson, deputy chief herald of the body that oversees the design and certification of every official coat of arms in Canada.

Patterson said heraldic symbolism is focused on both tradition and progress in their art. This has led to the enduring presence of the centuries-old practice.

“Heraldry does always have this — not quite intention, but a balance between what is traditional and what is familiar because we have inherited this tradition that has existed for hundreds of years,” Patterson said. “One of the reasons it’s existed so long is that it is adaptable.”

Part of the heraldic authority’s purpose is to combine a vast library of historical symbology with modern, creative ideas. Patterson adds originality is always a priority.

“We want something that will be meaningful but also unique, and express something special about that person or organization,” he said.

Cultural landscape

Patterson also noted the evolving nature of Canada’s cultural landscape, and how this interacts with progressive change within the field of heraldry.

“In different countries, different traditions emerge,” he said. “So it’s not something that necessarily changes instantly, but we look at ways that within the framework of the heraldic system, we can say something new. Part of that is responding to changes in Canadian society; part of that is bringing in this traditional system which works very well, and bringing symbols and elements from other cultures.”

Ouellette said there is no reason to delay changing the coat of arms any longer.

“Let’s do it now, because if we really believe in reconciliation, (these symbols) are the things we start changing along with the little things within the whole system,” said Ouellette.

“With housing, with education, within economic development, within political representation; all those things can be done at the same time, little bit by little bit, with people working on it,” said Ouellette. “Then one day you wake up and – oh! We’ve achieved reconciliation. But if we don’t take those steps, we’ll never achieve true reconciliation.”