When Canada’s capital was in lockdown, the doors to the city’s national and local galleries and museums were closed, but much was still happening inside. Capital Current’s Preslea Normand interviewed numerous officials from some of Ottawa-Gatineau’s leading cultural institutions about how they faced pandemic challenges and adapted their curatorial work and public outreach to life in COVID times.

The First Days of Lockdown

When the first lockdown began, Laurena Finéus and Sarah-Mecca Abdourahman were graduating university as emerging artists and preparing for their graduate exhibition and critique sessions respectively. A chance to show their work to people already in the art world and have feedback from their peers — a process that would help them find their footing as they went off into the world and see where their work as artists was headed — was lost.

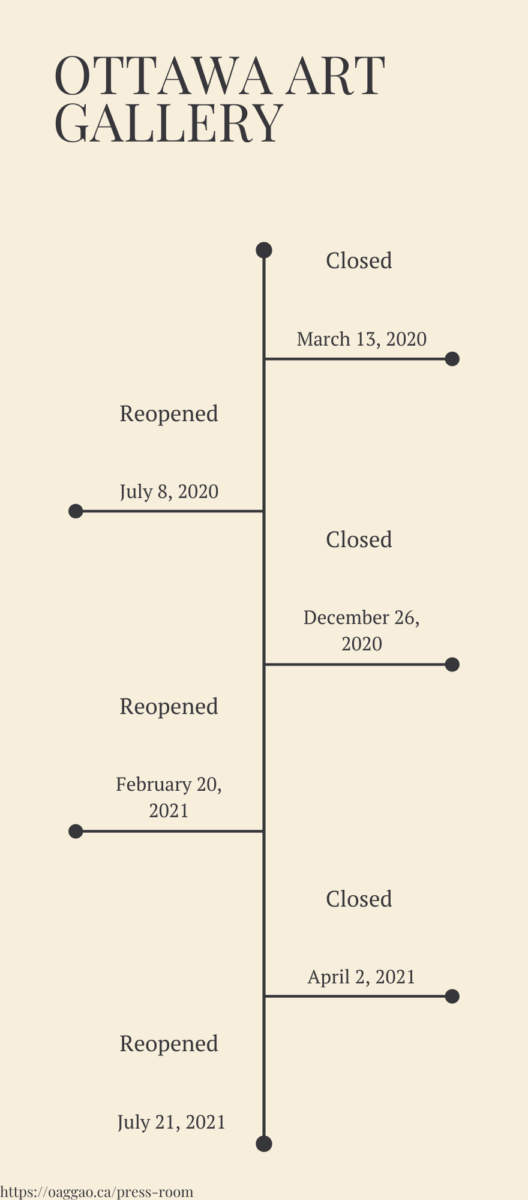

That led Finéus to seek a sense of community and connection, which she found in Abdourahman. The two had been following each other’s work on social media and then made the decision to share a studio. When the call was issued for a Black female artist to work on a mural for the Ottawa Art Gallery under the mentorship of the acclaimed Toronto artist Curtia Wright, Finéus applied, and encouraged Abdourahman to do so, as well.

The gallery said that their work complemented each other’s so well, they couldn’t decide between the two of them and asked would they consider working together? So, the wonderful coincidence led Finéus and Abdourahman to work on the mural as a duo.

The initial plan was to have the artists working in the space with Wright present while the gallery was open to the public so passersby could see the mural in progress through the window to a large, white-walled room filling up with colour.

Instead, because of the pandemic, the artists worked alone in the space, with Wright calling in lessons and advice as the project progressed.

Commercial gallery and shop co-ordinator Siobhan Locke noted the drastic change from the crowds at an opening at the OAG days before the lockdown, to the immediate shut down and the quiet that followed. She called it meditative and tranquil to be in the space when the doors were closed.

“I think it did feel like a nice balance to the sort of chaos that was going on and kind of a calmer place to be — and just to be reminded of the value of art in people’s lives,” she said.

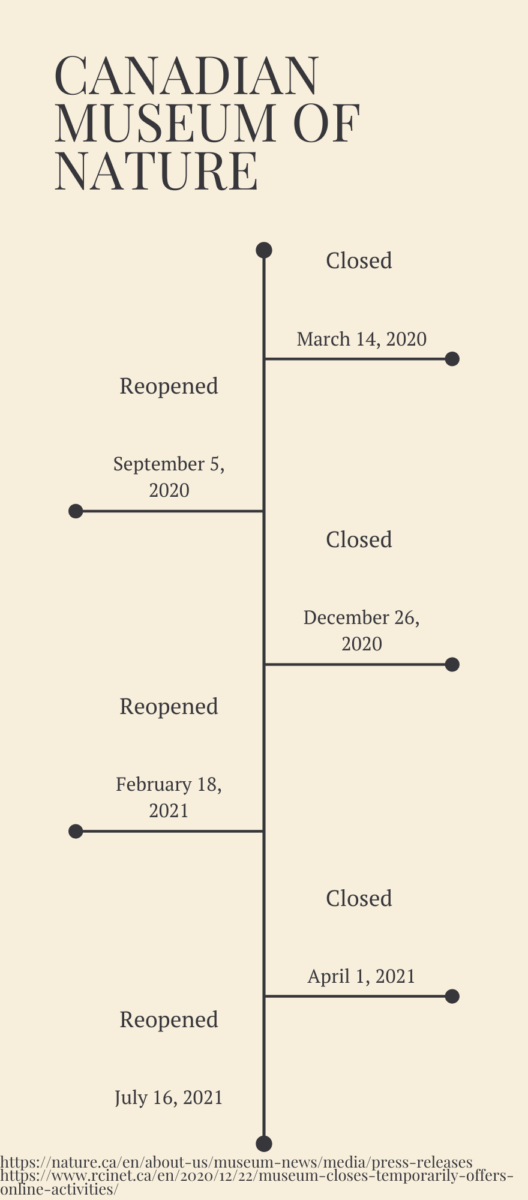

Gerald James, head of visit planning at the Canadian Museum of Nature, recalled Friday the 13th — two days after the World Health Organization officially declared the pandemic in March 2020 — as the day he first heard of the lockdown. After an impromptu meeting with the president of the museum, his team started refunding the many tickets that had been sold, especially with one of the museum’s signature Nature Nocturne events and March Break coming up.

“I think we got just about everything done within three days, which was actually pretty phenomenal,” he recalled.

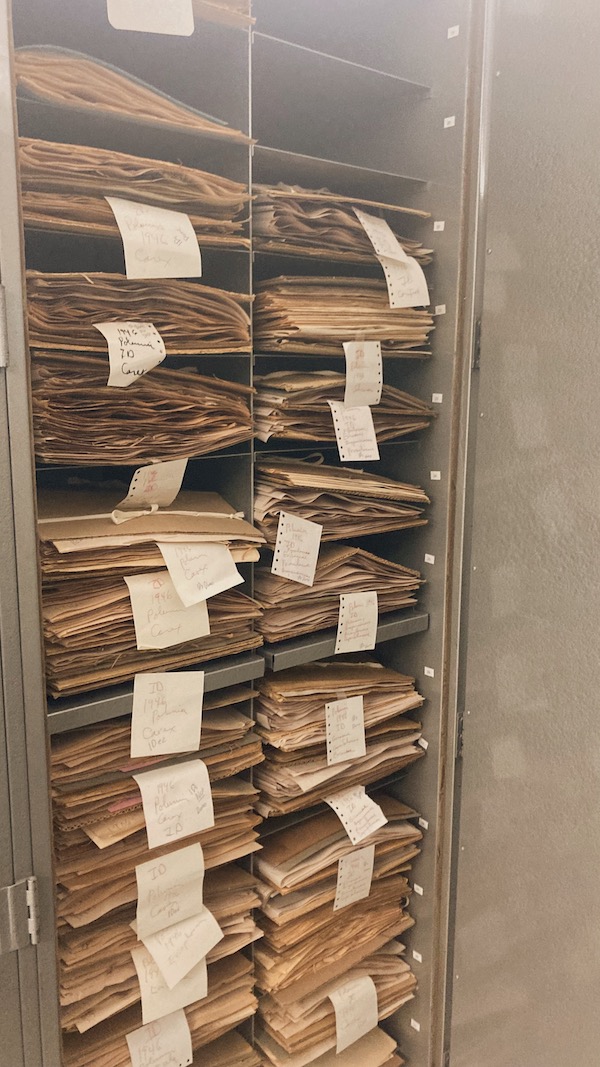

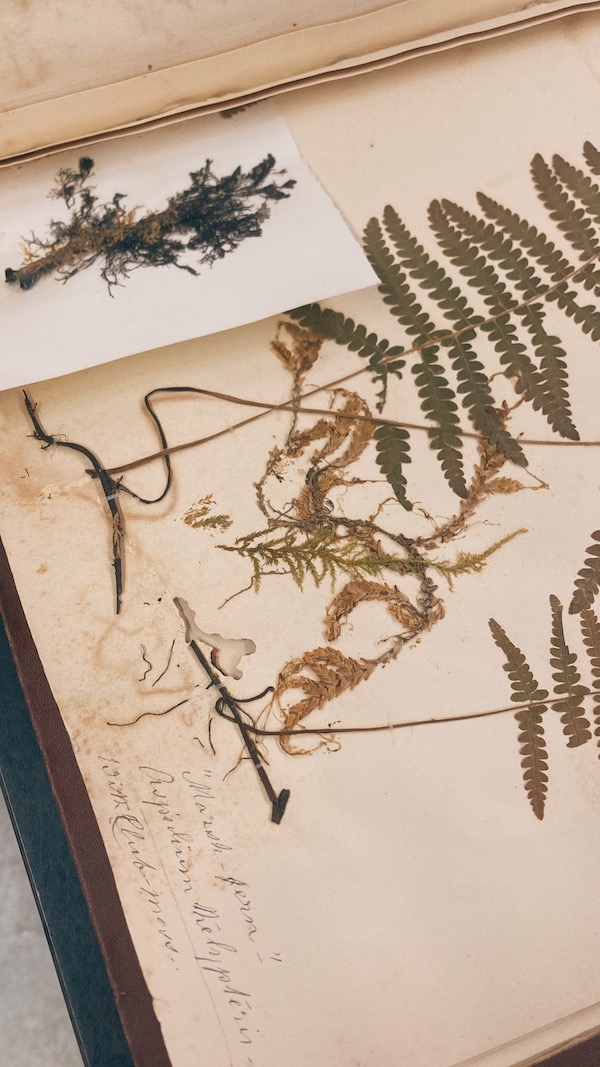

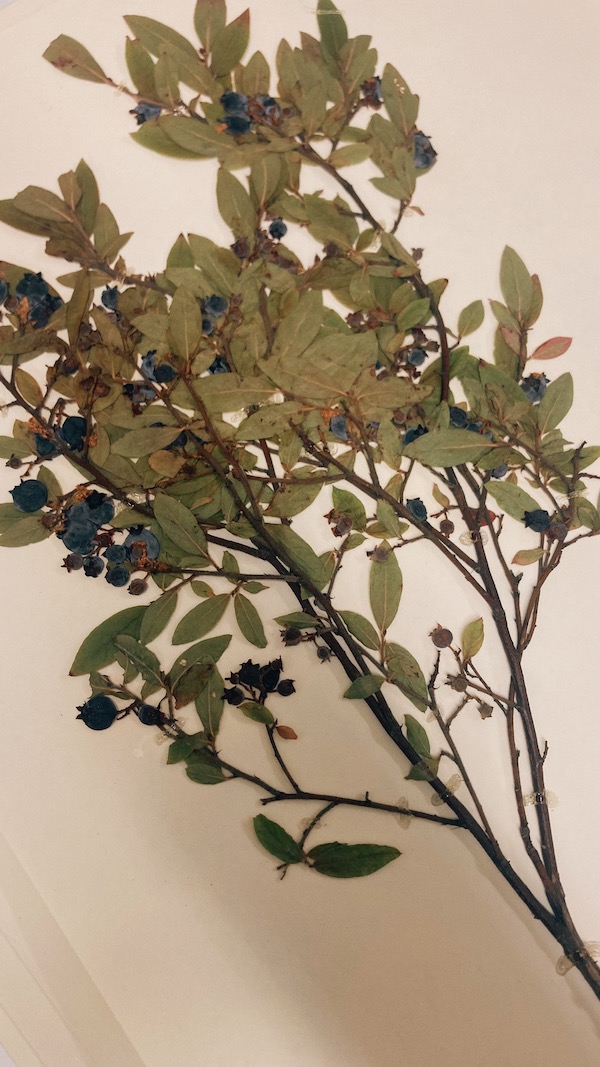

Jennifer Doubt, curator of botany at the Museum of Nature, spends most of her time at the National Herbarium of Canada, the country’s 139-year-old archive of more than a million historical plant specimens. It is located in Gatineau, at the museum’s research and collections facility. She said she can recall the first lockdown very clearly.

After planning for more than a year to expand the museum’s herbarium — a rare opportunity — a truck was on its way with 100 empty cabinets for the ever-growing collection.

“It’s pretty vivid,” said Doubt. “The truck was arriving the first morning that we were all supposed to stay home, so there were lots of logistical questions. … Everybody was trying to wear gloves and distance and it was a crazy situation to be in.”

Doubt and three other colleagues unloaded the shipment, cleared off the packaging materials and inspected the cabinets by flashlight, dusting them out to ensure there wouldn’t be any pests or dirt entering the delicate system of the herbarium.

[Photo courtesy CMH]

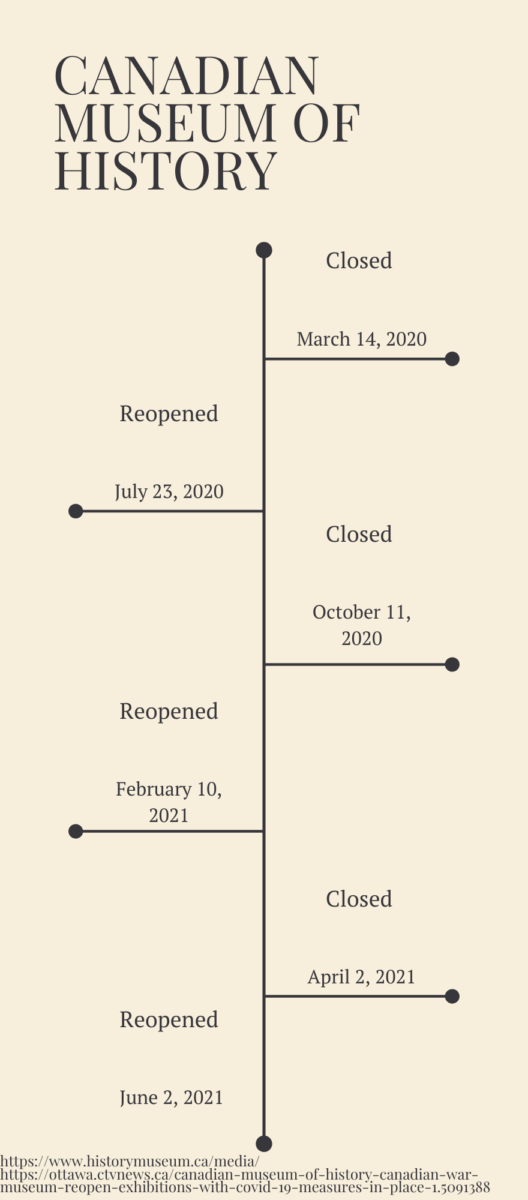

Over at the Canadian Museum of History in Gatineau, director general Chantal Amyot was on a business trip for a travelling exhibition in Washington, D.C. and was informed that she could not come back to work in Canada for 14 days, as she would have to quarantine. She told her team she would be back in two weeks, and she ended up not seeing them for months.

“You leave one day, everything is absolutely normal — and I never came back to anything normal,” Amyot said wistfully.

From Ghost Town to Gallery and Glass Tower

On days when they would head into the Ottawa Art Gallery to work on their mural, Finéus would come from the east end and Abdourahman from the west on empty trains and buses to get to the centre of the city. The Byward Market “almost felt like a ghost town,” according to Finéus.

“I think doing the mural felt like kind of bringing the streets back into the space itself,” she said.

With the only other people on site security personnel and collections technicians, the artists were mostly alone in their work space.

Abdourahman described it as “that feeling when you’re in a mall and it’s closed down — and you’re a kid, and you just want to be there alone. So it was kind of nice in that sense.”

She added: “It turned into our little home.”

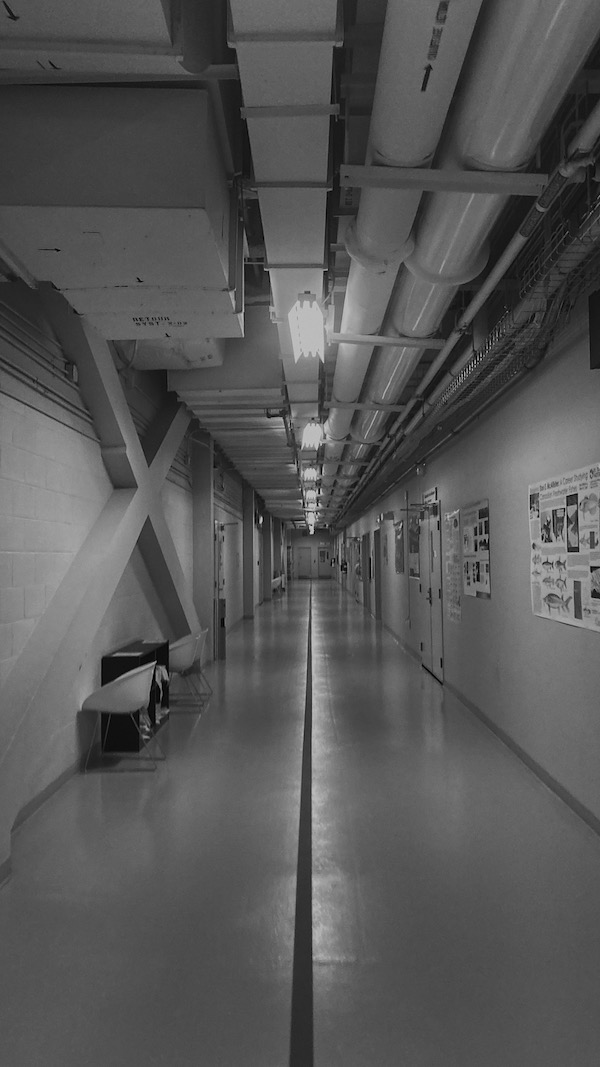

James remembered the first time he went into the Museum of Nature alone. “Now we have to go through shipping and receiving, which was a completely new experience for me, as well. I didn’t even know where it was.”

That entrance is a massive garage door on the side of the McLeod Street museum in Centretown, which leads to the building’s lower levels. The light from outside streams into a dimly lit docking station, where up above in the rafters hang rows of hockey flags that belong to the man who spends his days working there.

Stuart Baatnes, head of animal care at the Museum of Nature, is used to being in the museum when it’s quiet, as he starts his days at 6:30 a.m., well before the place opens.

Still, he said, there was an element of strangeness to the emptiness “looking out the glass tower, looking down at Metcalfe Street during the day and not seeing anybody or any cars.”

“That was kind of the unique thing … for such a big city,” he said, “I was able to shave 15 minutes off my commute time because there were no cars on the road.”

The Museum of Nature’s Doubt had the experience of working and living in two different provinces. This meant driving across the Ottawa River each morning and having to provide a badge to police officers at the COVID-19 checkpoint. “So going to work when that was up was also kind of surreal. Many of us live on one side of the river and work on the other, and in Ottawa, I don’t know, I feel like I didn’t really recognize it as much of a border until the pandemic.”

Behind the Closed Doors

Despite the emptiness, much was happening behind the doors of the museums and galleries while the city was in lockdown.

As the young artists worked on the OAG mural, Finéus described the process of watching the work come to life as if it were an actual creature moving and expanding of its own volition and leaving them swimming in it.

“As we were making and growing the piece, it was kind of absorbing us within it, and that was a very new experience, I think, to the both of us. Because we never really did work that was this large,” she said.

The process taught Finéus, who is immunocompromised, that boundaries are important when it comes to making art, especially with something as demanding as a massive, three-walled mural.

“We really had a lot of ambition as to how we wanted to have our vision come to life … and we were there, like, every day of the week. Security at some point was, like, ‘Are you guys OK?’” recalled Finéus with a laugh.

The experience taught her that health in artistic endeavours is so significant, noting that the nature of an artist’s mindset is perhaps to set that to the side at times. “We’re always in that mentality of scarcity as to — we have to work because there’s no one else to tell us to work.”

A year after the height of the anti-racism protests of 2020, Abdourahman said she was considering how to incorporate Black Lives Matter in tandem with Filtered — the theme of the exhibition that would include the mural and surrounding artworks.

She explained how Black Lives Matter affects their lives daily, how the filtered realities of news media depict their trauma, and how having a year to process the summer of 2020, after the murder of George Floyd — when everything was at its most intense — allowed the two artists to heal before setting out to create.

“Suddenly people were like, ‘Oh my God, Black people exist and they make art, too!’”

— Laurena Finéus, co-creator of the mural Carved Reflections at the Ottawa Art Gallery, on the summer of 2020

With so much coverage heavily focused on death and mourning, the Hatian-Canadian Finéus and Somali-Indian Abdourahman sought to showcase the countless aspects of Black life that do include mourning, but also power and joyful moments such as a day on the beach, with the intention of not inflicting more trauma on their Black audience.

“There’s many different stages of grief as being a Black Canadian or American and witnessing all of this you go through the feeling … the trauma and the guilt … that you should do something about it. But then, after, we were really seeing that sometimes you can only take care of your own mental health, so that’s where the power really comes in the rest,” Abdourahman explained.

“Often in the media, the representation is traumatic or pain, but you don’t really often see Black people just resting — that are not fighting, just staying still. So I think that’s what we were trying to showcase,” she said.

At the Museum of Nature, Baatnes and his team were consolidating all the animals, moving them into the lab to optimize working conditions in ways that would allow for minimal contact between whoever was in that day to look after the creatures, security guards and anyone else coming into the building.

With the closures, the abrupt end to exhibits and the disruption to the flow of deliveries, the butterflies and the arctic cod eventually died. “We still maintained and fed them, and looked after them until the very end,” said Baatnes.

Alternative methods of securing food and other necessities were arranged to allow work to continue. And for Baatnes, after the initial changes, his routine was relatively the same as before the pandemic. “Although it was altered, it was still consistent,” he said. “So come and work the same amount of hours, except there was nobody here to talk to.”

Except, perhaps, the animals?

Baatnes laughed. “That’s it! And I think they got tired of me talking to them. so . . . ”

Specialists at the Museum of History kept busy with the transcription of archival documents, but Amyot was full of emotion — even in retrospect — at the state of the building without its cherished visitors.

“This needs to be shared. And it felt — it hurt. It hurt that we couldn’t.”

— Chantal Amyot, director general of the Canadian Museum of History, reflecting on exhibitions during the lockdown

In recalling the situation, she sounded on the edge of tears. “The museum is a place that is alive, full of people, and going in there in that complete silence — and just us in the museum — was very strange. It is meant to be a place for sharing.

“In one sense, you walk alone in such a magnificent building,” she continued, “and you’re still struck by the beauty of it. And you feel extremely privileged to be there, but at the same time everybody was so sad because it has to be alive. … As I walked there and I heard the echoes of my steps in corridor — in the big halls, because our spaces are so huge — I kept thinking how to get people back in here, people need to get back in here.

“I’ve always felt that and I’m sorry to keep repeating it: This needs to be shared. And it felt — it hurt. It hurt that we couldn’t.”

Doubt illustrated what it was like to be in the herbarium, a place that is already disproportionately large in terms of size of the building and the number of people working there. The 75 or so people at the facility can disappear quite easily, she said, and even on a busy day it can seem empty until you go from room to room.

“It looked pretty normal when you first went into the hallway, but as you moved around to do whatever it was that you needed to do, then it sort of became more spooky, like ‘No, where is everybody?’ … Every place you went was just empty and quiet.”

The Shift from Material to Virtual

When the museum doors were closed, a conceptual shift from thinking about material objects to virtual ones was key to having the doors open in a different way — not only to local residents or people passing through the city, but to people all across and even outside of the country.

While the transition to online museum- and gallery-going has many positives, there are certain things that cannot be captured virtually, and which can only be authentically felt within the museums and galleries themselves.

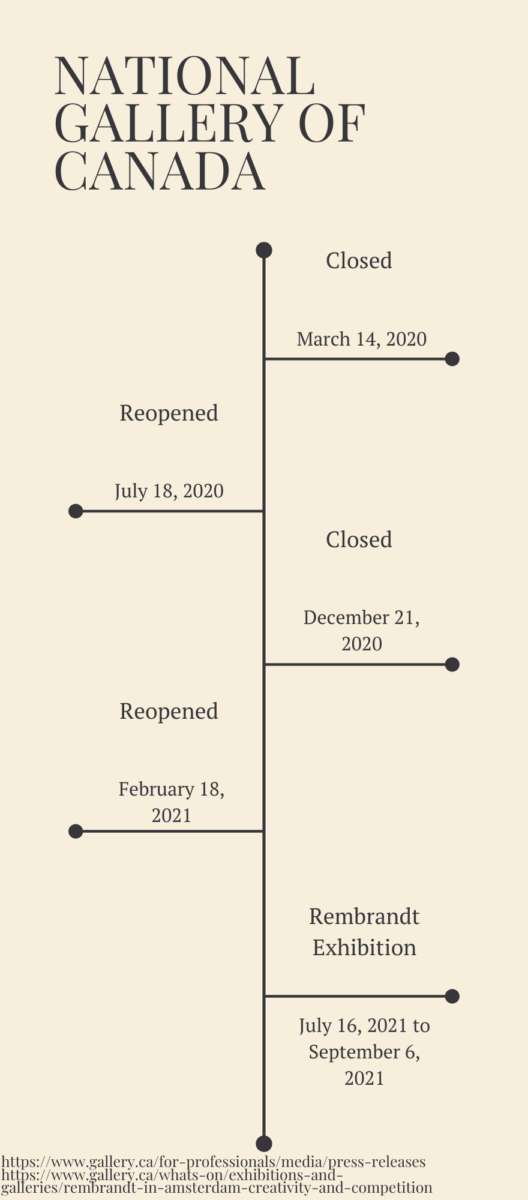

Gary Goodacre, chief of visitor experience and public programs at the National Gallery of Canada, spoke about what is lost in the virtual replications.

“You’re seeing the real witnesses of the past right there in front of you.”

— Chantal Amyot, director general of the Canadian Museum of History, on seeing artifacts in the museum

The scale, the ability to move around something, the context, the intricacy, even the ability to imagine where something has come from, who made it, what it has lived through to get to where it is now. The social dimension, the connections that can be had in witnessing art, understanding the thought process of curators in the midst of all the artworks, the conversations that arise in the three-dimensional space. The thumbnails identical in depth and proportion don’t cut it.

“The materiality of it,” he said, “is really important.”

Goodacre likened the experience of seeing art to taking a trip — “a combination of travel and visiting with friends that you haven’t seen in a while, so you kind of see things that are new to you that you never would have seen.”

He recalled seeing the long-awaited Rembrandt exhibition delayed because of the pandemic. “Here it is in Ottawa, and I’m standing like five feet in front of it,” he said.

“It’s about connecting people with ideas that maybe are new to them,” he said, “or maybe connecting them to things that they know but in a way that creates the opportunity for them to see things in a new way.”

Locke, from the Ottawa Art Gallery, echoed Goodacre’s words on the shift to virtual, emphasizing the unique nature of certain pieces — such as installation artworks — which require one to “experience it in a more bodily way,” she said.

However, according to Locke, the lockdown led to more connections between the gallery and the local arts community, and there was an outpouring of support for the artists from Ottawa-area residents looking to support local institutions.

You’ve heard of curb-side pickup for food, but what about for paintings and sculptures? Locke said with the help of technicians, they were able to facilitate sales using curb-side transactions.

As well, the sales began to expand nationally and even internationally, as exhibits were shared online.

At the Museum of Nature, James said the shift online allowed for a much more efficient ticketing system to develop, doing away with lines circling the building in the past.

Baatnes participated in the production of online content, as well, filming behind-the -scenes footage explaining his role in animal care. Still, he noted that the multi-sensory experience of being at the museum remains unmatched.

Amyot had a similar point of view: “There’s something that you get physically when you see, when you go in front of certain artifacts and that can’t be replicated.

“You’re seeing the real witnesses of the past right there in front of you,” she added, while also pointing out that there is value in being able to go deeper into subjects when you are sitting at the computer.

As for the herbarium, it is a treasure trove of plants from all over the world, some going back as far as the 1700s. The uploading of high-resolution images allows more access to the collection at a much lower cost than travelling to visit the herbarium, and without the preservation risk of sending rare specimens out on loan.

“So, it helps a lot, but then of course there are many things that you can’t do with an image,” said Doubt. “You can’t move anything if you need to lift up a petal and see the back of the petal or the flower — you can’t do that with a photograph. You can’t take pieces off and analyze their DNA. You can’t put it under a microscope and zoom in on tiny features that are difficult to see with the naked eye.”

On top of that, there is the wondrous element of being able to hold in your hands something so precious, knowing that it has lasted for such a long time, and that there is so much history attached to it. These experiences can’t be had in the same way from seeing a photograph. At least, not in a world where we are bombarded with photographs throughout each and every day.

The ‘Living Thing’ Reawakened

The general theme expressed by museum and gallery officials in different corners of the city — tucked away in their respective cultural hubs, labs and mural spaces throughout the pandemic’s lockdown cycles — was that reopening was always on all of their minds.

“I felt like a school kid on the first day of school.”

— Chantal Amyot, director general of the Canadian Museum of History, on reopening

When the Rembrandt exhibition was finally opened at the National Gallery, “I was nervously at the top of the great hall … peering down the colonnade,” recalled Goodacre. Upon seeing people in the gallery once more, it felt “like you’re awake again,” he said.

At the Ottawa Art Gallery, there was a slight delay in reopening in the late summer of 2021, but Finéus and Abdourahman welcomed the extra time to work on the mural — knowing that it would be up until January 2022.

“Whenever people see it, they’re like, ‘Wow. I didn’t realize you painted all the way to the top,’” said Abdourahman.

When the OAG finally opened up the first time, it went from being silent to being filled with people — “including the mayor,” said Locke.

She said the sweet part of the reopening was seeing people “have conversations about art again. It was definitely a good mood lifter.”

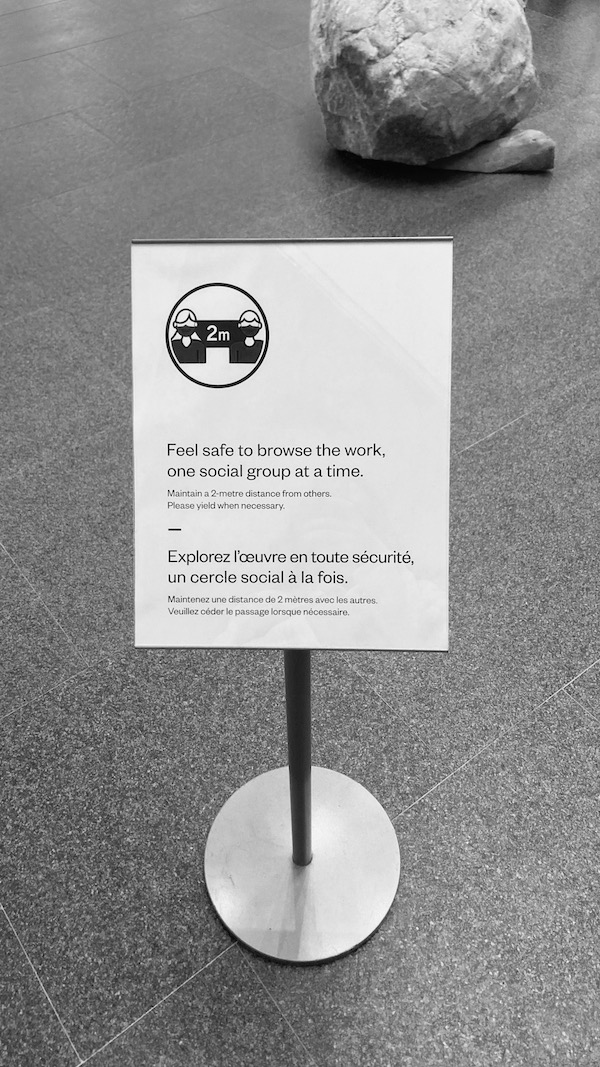

For James and his colleagues at the Museum of Nature, there was a party — or so he called it. The visit planning team was laying down all the signs throughout the museum for directional flow that would ensure the safety of visitors.

“The first time coming in after about three months off, you were so happy to see another face, to talk to someone,” he recalled. “You have conversations with someone you’ve seen twice before and you’d sit and chat for half an hour because you were so craving that attention, that conversation, that social interaction with people.”

With certain times still very quiet at the museum, there’s now music playing in the atrium, to enhance the atmosphere.

James explained the true essence of the museum is reliant on the presence of people, and how even the anticipation of people creates a difference between the quiet during the pandemic, and the quiet in the mornings before opening to in-person guests.

“The first time coming in after about three months off, you were so happy to see another face, to talk to someone.”

— Gerald James, head of visit planning, Canadian Museum of Nature

“It’s like the museum is a living thing. I know it’s crazy as it sounds, but . . . the museum knows that people are coming and it’s excited and that you’re getting revved up. But when no one’s coming in … it’s so quiet and dark and not lively at all. It really needs something to bring it alive again.”

Amyot reminisced about the very first reopening being full of hope. And while the second and third were more difficult, they were still full of joy, and “rekindled something of the excitement of working together.”

“It was the summer of 2020,” she said. “I felt like a school kid on the first day of school. It’s as simple as that. And you know, I’m in my fifties, it’s been a long time. But . . . you feel excited and nervous and the sense of newness, all of that. You know you’re going into a familiar environment, and yet it feels new. It felt exactly like that.”

A sunny autumn day in the National Gallery

The National Gallery has been open for nearly four months now, so I went to see how it would feel to be back in the space after its recent hibernation.

I sat on the benches overlooking the garden court, and angelic choirs from unseen speakers filled the silence that was otherwise only filled by delicate footsteps. My own steps rang out like thunder as I winced from above, attempting to quiet the touch of black boot on old hardwood.

It was a sunny autumn day, nearly the weekend, and there was almost no one there. The atrium, the stairwells, the colonnade, the garden court: empty.

It’s more uncommon to stumble across a stranger in one of the high ceiling spaces, than to wind your way through and see no one at all.

The echoes linger strangely, reverberating for a little longer than seems natural, holding onto the sweet sound of voices that these stone walls missed so dearly.

The necessity of the institutions in times of crisis

It may still be some time before the museums and galleries are bustling with hushed voices at full capacity once more, but their role will continue long after the pandemic is a distant memory.

Finéus shared that the way she sees it, museums are often “scared of the immensity of the role that they do have and how to best start and how to best reach into their communities.”

“This is when they are most needed, really, because they hold so much moments of joy, but also moments of pain,” she said. “And they have to make sure that they respectfully try — even if they stumble upon the road.

“We’re paying for these places, and if they’re not really making the work have us feel included, then what are institutions for, right?”

Abdourahman spoke about access to films and television and music during the pandemic, but the lack of access to live viewing of paintings, sculpture and performance art. “It feels nice to be in person after a whole lockdown. … When they’re open, it offers a sense of escape.”

“It feels nice to be in person after a whole lockdown . . . When they’re open, it offers a sense of escape.”

— Sarah-Mecca Abdourahman, co-creator of the mural Carved Reflections, Ottawa Art Gallery

Notably, what one witnesses in a museum and a gallery is of utmost importance during trying times. To see the resilience in nature is to know that we, too, have resilience as a species.

These repositories of fine art and historical objects can act not only as places of respite, but as storehouses of knowledge from the past that can be applied to the present — literally and metaphorically.

The Canadian Museum of Nature opened in 1912, only a few years before the outbreak of the influenza pandemic of that era. James said that although there were no notes left behind for today’s museum staff to draw on as to how the institution weathered that storm, anyone working at the museum in the future will be well-equipped from everything staff members have had to source for themselves in the past two years.

Amyot noted proudly the recognition of museums as “the number one trusted source of information for the public before anything else, and that is a huge responsibility. So you really have to uphold that, and how very seriously we take that.”

Amyot is starting her 34th year at the museum, “so you can tell that I love it.”

“I call it a place of respite, because you go there, you are in a completely safe environment. It’s a very nourishing environment,” she said. “You go there to resource yourself, you go there to learn, you go there to feel. … It’s an intellectual and physical space. It’s fun and it’s serious. … It’s really all of the above, so that’s quite amazing. It’s a unique proposition.”