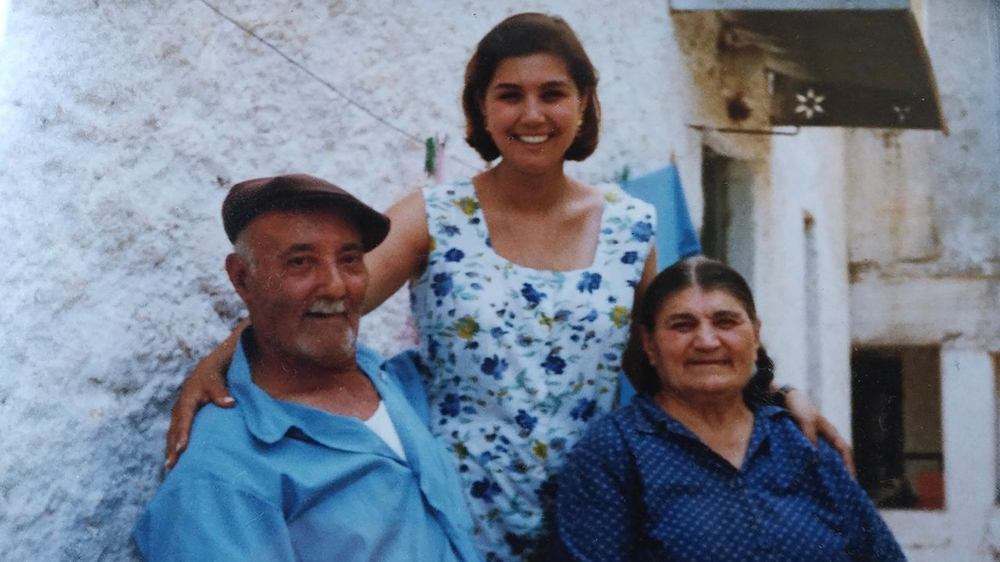

Sophia Aggelonitis knows first-hand the anxiety of a wandering loved one who suffers from dementia.

When her grandmother wandered from her home in Welland, Ont., in May 1999, Aggelonitis’ friends and family assembled a search team to look for her. She said she felt fear and failure during the hours her grandmother was missing. “You’re panicked,” Aggelonitis said, “you think you’re never going to see her again.”

Aggelonitis’ grandmother Sophia Plagakis, after whom she is named, was found four hours later in a ditch, bruised, cold and scared — and just a few blocks from her house. “It was just a miracle we found her; I cannot even imagine a senior wandering in this cold,” Aggelonitis said, speaking on the phone on a -20 C day.

Aggelonitis founded Silver Alert Canada in 2018, after 10 years of advocating for the system. Silver Alert is a public notification system used to help find wandering people who suffer from dementia and related diseases like Alzheimer’s.

Similar to the nation-wide Amber Alert system that notifies the public about abducted children, Aggelonitis said she hopes Silver Alert can help mobilize local police, media and the public by broadcasting the missing person’s name, description and the area where they went missing.

The former Liberal MPP brought her concerns to the Ontario government when she was the Minister Responsible for Seniors from 2010 to 2011. Though the government showed support for the idea, the program has yet to be implemented.

Aggelonitis said Silver Alert is needed on a national level especially for communities that don’t have local police and rely on the RCMP.

There are roughly 200,000 people in Ontario who suffer from dementia, according to the provincial government.

Last May the Canadian Senate recommended that the House of Commons consider adopting a Silver Alert program but so far no debate on the question has begun.

Meanwhile, Alberta, British Columbia and Manitoba have all moved to create alert systems. Alberta and Manitoba included Silver Alert programs in their Missing Persons Acts in 2017. British Columbia’s effort was not enacted when it reached the legislature in 2014. A citizen-run website and social media accounts have instead been used to disseminate missing persons alerts in B.C.

Aggelonitis says she doesn’t believe funding or technology should be roadblocks to installing a national system. She said she is hopeful that Silver Alert will get more attention from the federal government now that Filomena Tassi has been appointed Minister of Seniors in August 2018. In the prime minister’s mandate letter to Tassi, the minister was instructed to “work with the Minister of Health to engage with stakeholders and parliamentarians on ways to address dementia.”

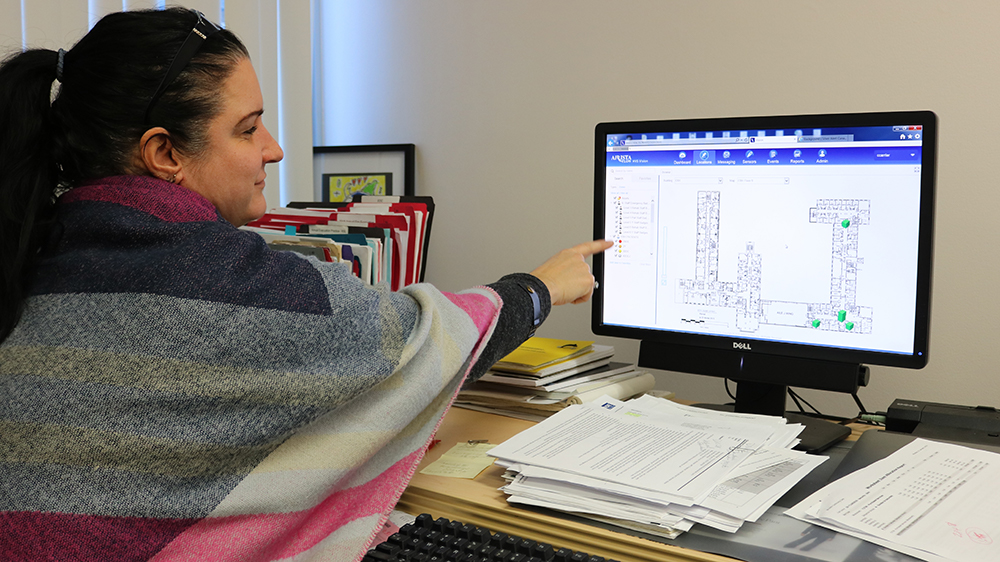

In Ottawa, the prolonged extreme cold this winter is a reminder of the potentially danger for someone suffering from dementia who has left their home. Christine Carrière, director of emergency management at Bruyère Continuing Care, said that even with GPS tracking and staff monitoring patients around the clock, residents with dementia can still slip through protections.

“Some of them are really determined and have made it out before we can actually prevent them from leaving the front door,” said Carrière. “But because the alert is so quick and we dispatch our first response, we find them within minutes. They never end up going very far.”

According to the Alzheimer’s Association, 94 per cent of people who wander are found within 2.5 kilometres of where they disappeared, but Aggelonitis says time is a factor, especially in cold weather.

“No matter how many friends and relatives you have around you that could go out looking for the person you love, the fact remains that minutes do matter,” she said.

In the time it takes for a family to discover that their loved one is missing and to call for help, a person with dementia becomes more vulnerable to harm. “Don’t waste time,” said Aggelonitis. “Call the police right away. Get their information out as quickly as possible.”

In many cases people with dementia become disoriented, often without warning, said Louise Nobel, executive director of the Alzheimer Society of Ontario for Ottawa and Renfrew County. Nobel said getting lost walking home, forgetting to dress properly for the weather, or mixing up night and day are just some of the ways dementia can affect a person’s memory.

“You may think ‘Oh, this will never happen,’” she said, “but 60 per cent of people living with dementia will get lost at some point.”

While there are many ways to prevent wandering, such as supervised day programs, in-home services and monitored retirement communities, having a backup plan for wandering is important, said Nobel. GPS devices, tracking phones, MedicAlert Safely Home bracelets and knowing a person’s habits can help track down a lost loved one faster.

Carrière also cautioned against being too reliant on gadgets. “Technology does improve, but we can never let our guard down,” she said. “It doesn’t matter what technology you use, there are always risks.”

Silver Alert systems operate in 36 states in the U.S. and have proven successful, especially in snowbird states like Florida, said Aggelonitis.

The Alzheimer Society has been working with the communities in Ottawa to train local businesses on how to understand dementia and how to interact with someone who has the disease. Nobel said this also means that there are more eyes on the ground. Confusion, pacing, trouble remembering, not dressing properly, and trouble handling money are indicators of someone with dementia who may need help.

For families like Aggelonitis’, the fear and pain of losing a loved one is still familiar. “It was one of the worst days of our lives,” said Aggelonitis. She said she hopes that the public will support the need for a national Silver Alert system. “I would say if anything it’s more important than ever during this weather.”