Heavy snowfall, freezing rain and below-zero temperatures have returned and so has the use of road salt on every street, sidewalk and pathway. But as icy conditions ramp up, environmental advocates are keeping a close eye on how much road salt the City of Ottawa is using.

According to Christopher Paquette, the city’s program manager for operational research and projects, Ottawa uses about 185,000 metric tons of salt each year.

“In order to ensure public safety, the City of Ottawa has a requirement to maintain roads during the winter to a prescribed standard based on provincial regulations,” Paquette stated in an email statement. “A de-icer is required to maintain roads to a bare condition, and the industry’s primary de-icing method is road salt.”

Matt Fyfe, a scientist with the local environmental organization Ottawa Riverkeeper, describes road salts as a category of mineral — typically sodium chloride — used as a de-icing agent on road and walking paths during the winter.

But while sodium chloride is essential for improving winter road safety, it can have detrimental impacts on aquatic wildlife.

“When water melts, it enters stormwater drains or it can go right into creeks and ditches, and those are habitat for aquatic organisms, micro invertebrates and macro invertebrates, and fish and even some plant species,” Fyfe said. “And all of these groups of organisms have different sensitivities to chloride, which can be toxic at different concentrations.”

In 2019, Ottawa Riverkeeper began monitoring the levels of sodium chloride in urban streams, creeks, and rivers around the city. Fyfe said the results have shown that Ottawa’s water sources can sometimes reach sodium chloride levels as high as those in oceans. This will be the third year of monitoring and the organization’s volunteers will be keeping an eye on 14 testing sites around the city.

“Over the course of the winter, almost half of our sites regularly exceed the toxicity threshold,” Fyfe said. “There are some sites in particular, where it’s especially bad. Those are sort of close to big infrastructure projects or next to highways. But even in residential areas, there’s a lot of salt that’s getting into the streams.”

Salt levels in urban water sources can sometimes be high enough so consistently that the issue is considered chronic, according to Kelsey Scarfone, the policy and campaign manager for conservation at Nature Canada.

“It’s a very unnatural disturbance that we’re introducing into their habitats,” she said. “It’s causing real problems, especially in the lower levels of the food chain. There’s a lot of really small creatures that are quite sensitive to the salinity of their waters. And, of course, these creatures are adapted to freshwater habitats that they signed up for.”

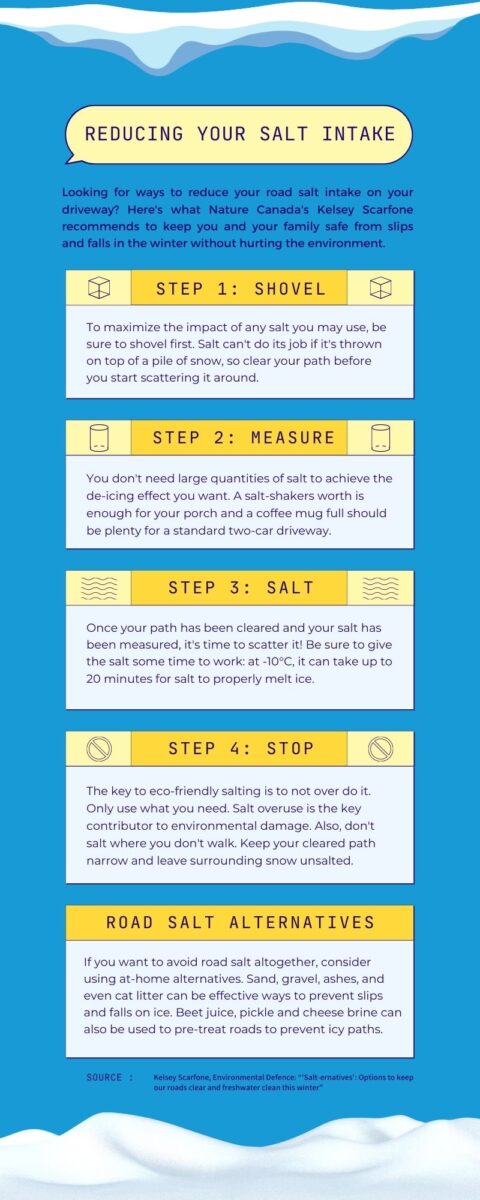

The problem, Scarfone said, is that there have so far been no alternatives that can produce the same de-icing that makes road salt an essential winter safety tool. While popular products like sand and gravel increase friction, only road salt has been able to break through stubborn ice cover.

But that doesn’t mean the negative environmental impacts are inevitable.

“The problem is that we’re using way too much (road salt),” Scarfone said.

While cities might be worried about liability from slips and falls on their properties, Scarfone argues that reducing salt use “should be a priority” for municipalities, not only because of the environmental impacts, but because of the cost.

“It’s wreaking havoc in a lot of ways,” she said. “They’re destroying not just shoes, but also infrastructure. It can be quite hard on all of our expensive infrastructure and also on our cars.”

Scarfone also said that while doing away with road salt probably isn’t an option right now, projects, such as Ryerson University’s road salt reduction pilot using a water-salt solution, have seen promising early success.

In his statement, Paquette said that the city has taken several measures over the years to reduce its road salt use, including developing a detailed salt management plan, and investing in computer controllers for salting trucks to more accurately control the amount of salt spread on roads.

He added that the city reports its salt usage to the Ministry of Environment annually, and that the municipality intends to review its Salt Management Plan for the third time in the first quarter of 2022.

“The city is proud to be a leader in salt management,” said Paquette, “and is constantly looking at new products and technologies to increase productivity and minimize the environmental impact of our operations.”