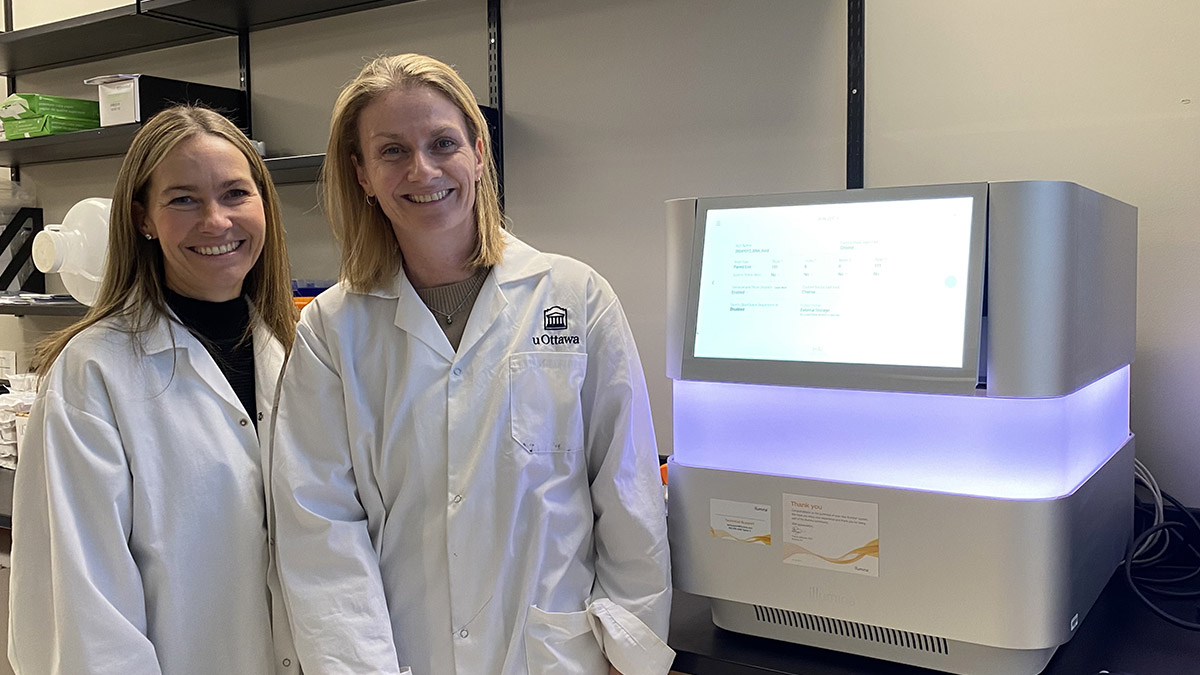

A University of Ottawa scientist who recently received a prestigious national award for her work is at the forefront of a revolutionary change in research that could make lab rats a thing of the past.

Dr. Carole Yauk is one of a growing number of researchers pursuing alternative testing methods amid concerns that animal experiments are too expensive, time consuming and have limited relevance to human health.

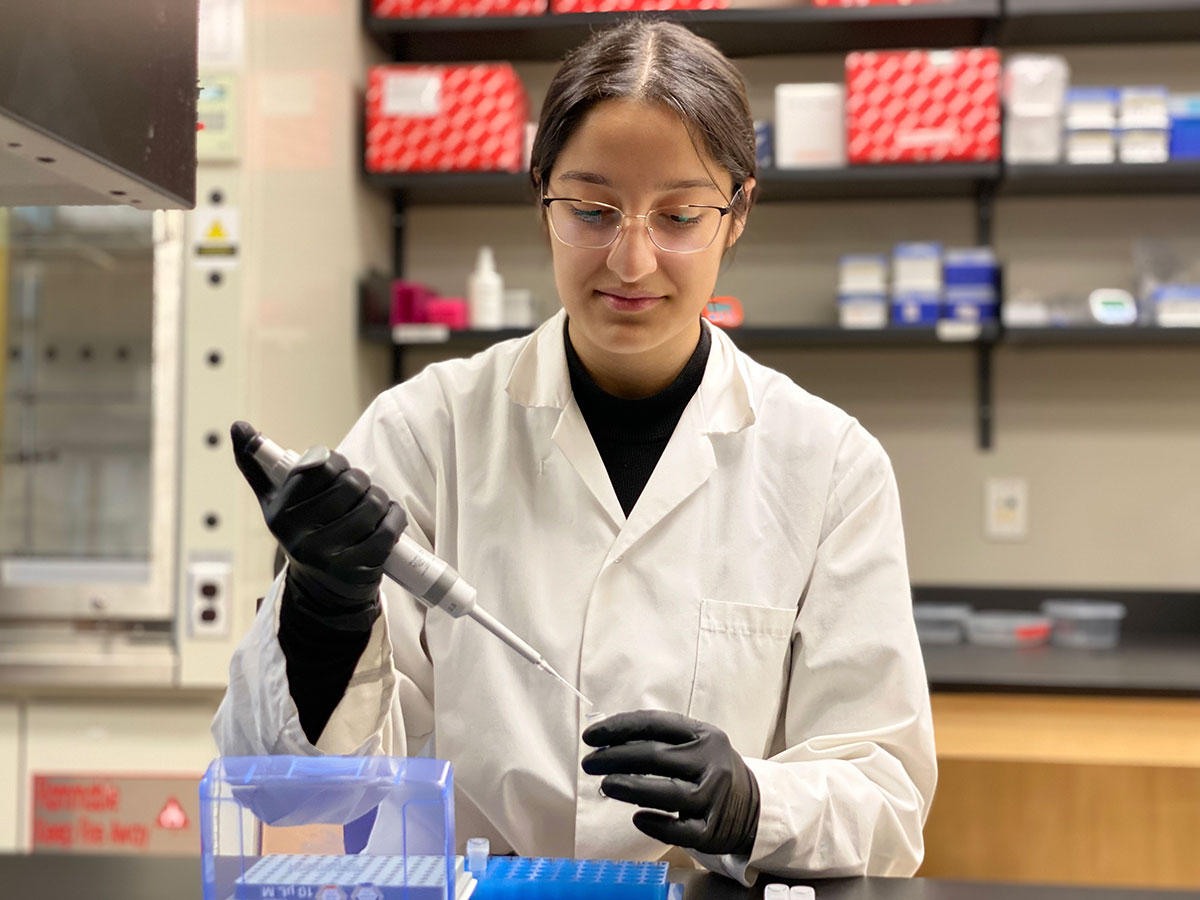

Conventional toxicology testing uses animals to observe the long-term physical effects of disease. Yauk and her team collect tissues before disease develops and measure molecular changes.

A standard experiment in toxicology is a rodent test to determine whether a substance is going to be carcinogenic. Such experiments typically take about three years, use more than 800 rodents, and cost several million dollars. In contrast, Yauk’s lab uses short-term (28-day or 90-day) studies that only require between 24 and 48 rodents.

“We can use gene expression changes to predict the dose at which disease-associated effects would occur in a long-term study,” said Yauk.

This work is part of a larger transformation currently happening in the field of environmental toxicology, which has its roots in a paradigm shift that took place in the scientific community 17 years ago.

“Toxicity Testing in the 21st Century: A Vision and a Strategy,” was a landmark report that caught the attention of the international scientific community, and the committee behind it was chaired by one of Yauk’s colleagues at uOttawa: the renowned epidemiologist and medical researcher Dr. Daniel Krewski.

“We asked ourselves one thing,” said Krewski. “How we can do toxicological risk assessment the best way, with no consideration of whether animals need to be reduced or not — just the best science.”

The publication laid out a 20-year vision for transforming testing methods based on advances in biology, and it called for a complete overhaul of how regulatory toxicology was done. Praised by leading researchers and regulators in the world’s top academic journals, including Science, it quickly gained acceptance from research agencies in the U.S., Europe, Australia and China — and was even translated into Mandarin.

“Immediately when a scientific committee says there’s a better way to do toxicity testing that doesn’t involve the use of animals, you make a lot of friends with the animal rights movement,” said Krewski. “It just turned out that the best scientific approach was to move away from traditional long-term animal-based tests to more rapid tests.”

‘Immediately when a scientific committee says there’s a better way to do toxicity testing that doesn’t involve the use of animals, you make a lot of friends with the animal rights movement.’

— Dr. Daniel Krewski, epidemiologist and medical researcher, University of Ottawa

Krewski is sympathetic to animal rights, but as a trained scientist he makes clear his priority is to protect human health. “The alternative of letting humans being exposed and seeing what happens is not an option,” he said. “But ideas on animal testing are changing because of better science.”

The number of environmental substances subjected to detailed toxicological evaluations is relatively small, and if health agencies continue to rely on long-term animal tests — which take years and cost millions of dollars each to do — they will make little progress on evaluating the thousands of chemicals that people could be exposed to either in the general environment or in occupational settings.

“New methods are not just cheaper, but a lot faster. If we need to regulate something, we regulate it now, not 10 years from now,” said Krewski. “That avoids potential public health risks that can be left unrecognized.”

Yauk is part of this shift towards “new approach methodologies” known as NAMs. She received the Canadian Academy of Health Sciences Fellowship for her research in toxicology testing related to the risks of cancer and other genetic diseases.

When she entered the field of genomics more than 20 years ago, she became aware of the possibilities of this area of research. “It was clear to me that we could use this for regulatory testing of chemicals to refine our studies with better ideas on the mechanisms driving toxicity,” she said.

On a broader level, NAMs have led to the recent amendments to the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, which regulates experiments that assess chemical substances to protect human health.

“This is a milestone that has happened over the course of the last year and a half,” said Tara Barton-Maclaren, a risk assessment manager at Health Canada who collaborates with Yauk on research to advance the use of genomics in regulatory toxicology testing. “The recent updating of CEPA specifically mentions the requirements to move towards the replacement, reduction or refinement of animal testing.”

Health Canada co-published a draft strategy in September and public feedback was received during a 60-day public consultation period.

One of the organizations commenting on the strategy is the Canadian branch of Humane Society International, an advocacy group that advances the welfare of animals in more than 50 countries. “On the whole, the draft strategy is a really good starting point and it’s very encouraging,” said Dr. Shaarika Sarasija, an Ottawa-based senior strategist of research and regulatory science for HSI Canada.

“One of the big things for us is that there are no timelines set, so we’ve asked that the government publish an annual report,” said Sarasija. “We have looked into the new substance program which is where a lot of the toxicology testing comes up, and we’ve identified tests that can be replaced right now.”

In 2022, Sarasija left her post-doctoral research at uOttawa, where she was studying Alzheimer’s disease in mice. Although she received generous funding and was starting a successful career, she decided to change professions and become an advocate for animal rights.

“I’m not sure if you’ve ever worked in a lab or handled mice — they’re social creatures, they know you, and they get familiar with you,” she said.

HSI has pushed for regulations that make animal testing a last resort rather than the default research methodology, with a future goal of completely phasing out the use of animals.

“I will never say you need to stop all animal testing today,” said Sarasija. “It is not necessarily because animal testing is giving you reliable data — in some cases it is all we have for the moment.”

Current invasive tests on mice in environmental toxicology include: inserting toxins into their digestive systems through force feeding, applying chemicals on to their skin to see if there is corrosion or irritation, forcing the inhalation of noxious vapours to see at what point adverse effect or death will occur, or injecting toxins into pregnant mice to see what will happen to their offspring. None of these long-term tests, which can last years, involve any kind of pain mediation methods.

NAMs include a collection of advanced molecular biology tests that are more predictive of human health outcomes, and the amendments to CEPA promote their use.

Advances in the field of environmental toxicology testing will have a trickle-down effect on all experimentation. Animal testing happens in different areas of scientific research such as pharmacology or in industries such as cosmetics. The use of animal testing for cosmetics is now banned in Canada.

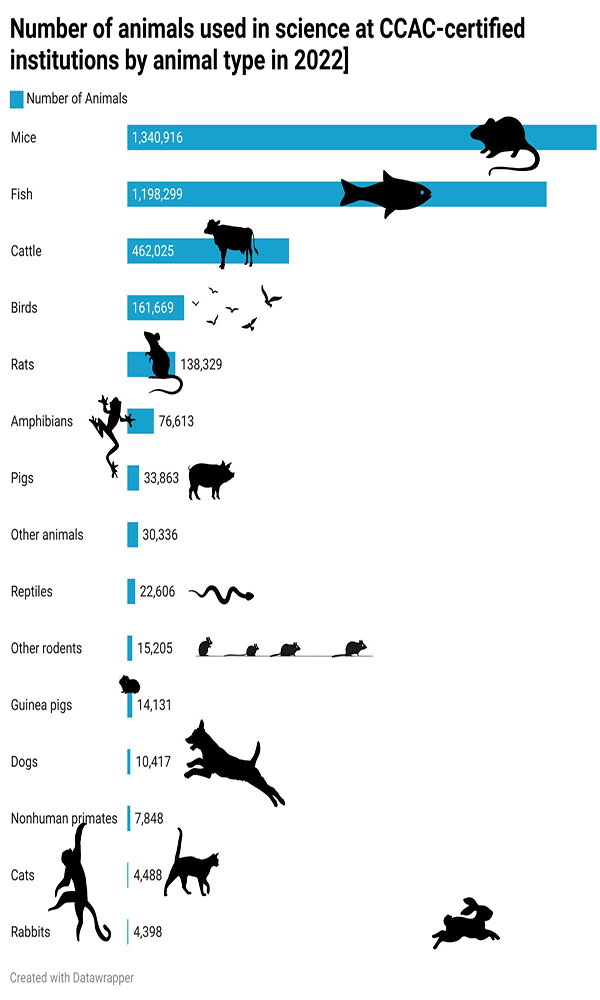

According to most recently available data from the Canadian Council on Animal Care, an organization responsible for regulating the ethical use of animals in science, 1,340,916 mice were used in Canadian research in 2022, a number that does not included privately funded studies.

“What was conventional wisdom is now the historic mindset,” said Krewski, discussing the changes since the visionary 2007 report. “Now that we have scientific methods that can get us the information that we need without animal tests, it’s a whole new ballgame.”