Content warning: This article contains brief descriptions of disordered eating that may impact some readers.

Whenever you try the latest edition of a fried chicken sandwich from a fast food restaurant, it’s obligatory to send a detailed video review to my cousins’ group chat.

On Sunday mornings growing up, my siblings and I would crowd around a Bundt pan on the kitchen counter and get sticky fingers from my mom’s fresh cinnamon buns.

One time my brother made Maryland crab cakes in a waffle maker and we laughed because we were surprised how good they turned out. And, of course, there were many times when loaves of banana bread were left to cool on wire racks after my mom saw that our bananas were getting too brown and needed to be baked. Slices of the bread would disappear within the hour.

These are just a few examples of how food is intertwined with my family and my childhood memories. As a result, it’s also tied to my identity — whether I want it or not.

I do want food to be part of my identity. I just need to work on getting there first.

I’ve struggled with eating for as long as I can remember, and it came to a head two years ago at the start of the pandemic. In 2020, I decided to lose weight — for personal, mental and social reasons. As I wrote in an essay for Her Campus at Carleton, all too soon I became obsessive: counting calories, tracking steps, weighing food on a scale, writing down pounds gained and lost down to the decimal. It was all I thought about, and I hated it.

In the time since that dark period, I’ve been fortunate and privileged to get mental health therapy and my relationship with food isn’t entirely negative anymore. On my best days, it probably edges on neutral. But lately I’ve come to realize that food can never simply be neutral for me, not only because it’s associated with disordered eating, but also because food has only ever been a positive thing in my family.

Asian families often express their love through food, and my family is no exception. In fact, every one of my family members — including (perhaps ironically) me — are self-proclaimed “foodies.” Our vacation itineraries are built around reservations at restaurants featured in Anthony Bourdain’s Parts Unknown, the famous food and travel show that aired on CNN from 2013-18.

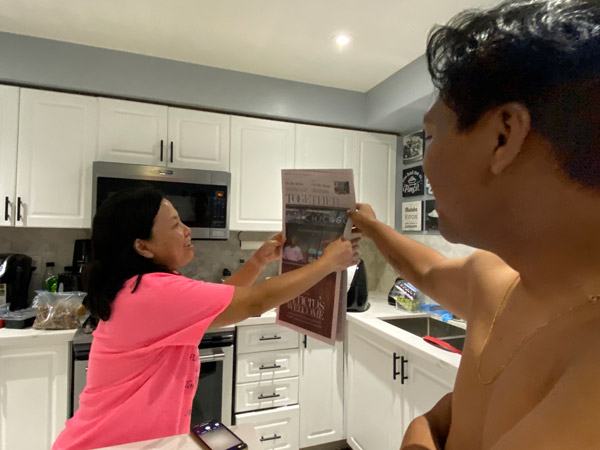

Every family event, whether Thanksgiving or a Blue Jays playoff game, by default comes with a spread of Filipino dishes. Last year, my two older brothers perfected their secret recipe and opened a Chicago-style sandwich shop in downtown Toronto, to much success and even media coverage.

We love food. I love food. This makes it hard to accept the asterisk it comes with.

I tried for a long time not to think about food’s place in my life, but it was difficult given how food was woven into nearly every memory my family made together.

I was confronted with this last August, during my brother’s wedding. I already wasn’t feeling too great about my body — my weight had fluctuated in the six months since I first ordered my bridesmaid dress, and even my trusted tailor couldn’t keep it from being uncomfortably tight. Not to mention, there were photos taken at every point of the big day, and for someone who has long felt insecure about her body image, this wasn’t ideal.

But it was my brother’s wedding, and I love him and my now sister-in-law more than anything in the world. So I sucked it up (literally) and told myself to have fun.

Late into the reception, a few hours after the three-course meal and well into cocktails and Abba’s top hits, my brother and his wife announced there would be a table of McDonald’s hamburgers and chicken sandwiches for guests to snack on. It was a funny, unique touch to the wedding that perfectly represented the couple, and everyone joyfully flocked to the table.

I shouldn’t have one, I thought to myself, even though the chaos of the day meant I hadn’t been focused on eating. I was hungry, but my thoughts started to take over.

I can’t let myself eat that stuff … this dress wouldn’t be so tight if … I’ll never lose weight like this…

I looked at everyone on the dance floor, laughing, smiling, swaying. Unwrapping their hamburgers, not a care in the world as they sang along to the music and cheered for the happy couple. And I was there, a part of it all, yet somehow still on the outside. My thoughts started to consume me, and the dress felt like it was getting tighter and tighter.

Why was I caught up with thinking these things when all of my loved ones were here, celebrating, having an amazing time? This is what happens when your relationship with food isn’t neutral. It becomes a part of you that can’t go away, even in those moments when you so badly want it to. It becomes isolating.

But in those moments — the dance at my brother’s wedding reception, the day my siblings’ sandwich shop was featured in the newspaper, the countless meals my family has shared together — food can’t be anything but a good thing. And when I am surrounded by my favourite people, I am not alone.

It’s okay for me to eat this, enjoy it and not feel bad about it, I thought to myself, as I reached for a hamburger. It’s okay for me to feel good about eating this.

So, I ate it. I had a hamburger, I danced and I sang with my family. It was one of the best memories I’ve ever made, and one of the tastiest meals I’ve ever had.

Food used to be the most stressful part of my day, and I’ll admit there are days when it still feels that way. I sometimes feel ashamed when I secretly wish for some sort of magic pill I could take once a day, one that had all of my nutritional requirements and would eliminate hunger, so I wouldn’t have to think about food in any way, shape or form.

But you can’t avoid food forever. I see my family smiling and passing plates of delicious meals to one another, and those dishes are symbols of our shared history. I picture myself as a young girl, sitting at the kitchen table, watching my mom as she cooks at the stove. I’m still not sure how something so integral to my family could become such a complex part of my life, but I’d rather accept this than fight against it.

Two years ago, I might have regretted having that hamburger at my brother’s wedding. Now, I’m not going to deny myself food, not at the expense of my own hunger, and not at the expense of a happy family memory. I’ve come to realize that I cannot separate food from the people I love and the person I am. I still have a long journey to go in reconciling my relationship with food, but it’s one for which I’m willing to work.

There is so much love to be had over bites, snacks and meals. There is so much to learn from the food that we share. To me, food is more than something I reach for when my stomach growls — it forms my identity, my culture and my family, for better or for worse.

For better, I hope. And I wouldn’t have it any other way.