The pop of a cork and the fizz of champagne flowing down the side of the bottle. The glug-glug-glug of wine being poured into a glass. The clink of a bottle cap landing in a stash of caps.

These are the festive sounds many associate with alcohol, as they use it to mark celebrations, relax with friends or simply to unwind after a long day of work.

But alcohol is also associated with other, more sinister sounds: the shrill beeping of hospital monitors, the rattling of gurneys and the clatter of IV stands.

That’s because alcohol is increasingly being recognized as a carcinogen, with even moderate amounts leading to a rising risk of a wide range of cancers.

Alcohol abuse can cause liver cancer, but few know it sends the risk of colorectal, breast and esophageal cancer soaring.

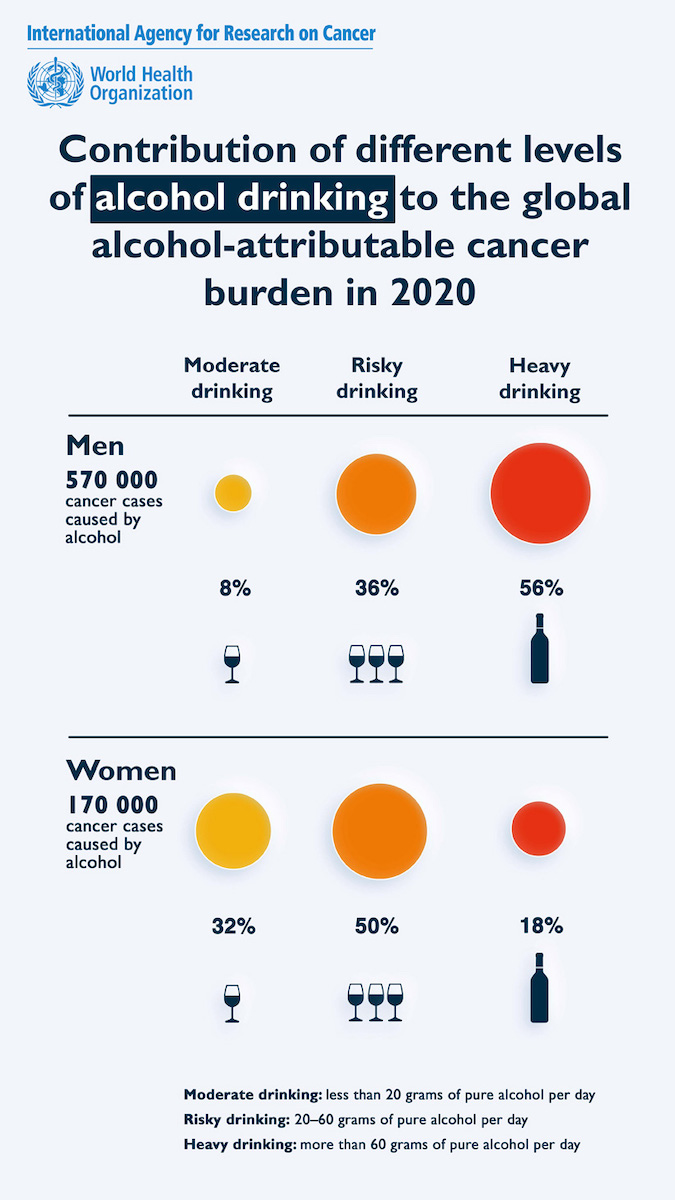

Globally, 741,000 new cases of cancer were attributable to alcohol consumption in 2020, with 7,000 cases in Canada, according to a study by the World Health Organization’s International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC).

Although the study found most alcohol-related cancer cases were associated with heavy drinking, researchers estimated that even light to moderate drinking – one to two drinks a day – contributed to more than 9,500 cases in North America.

Worldwide, the study found that moderate drinking contributed to one in seven alcohol-attributable cancer cases, totalling more than 100,000 cases in 2020.

Heavy drinking was associated with 56 per cent of the alcohol-linked cancer cases in men; for women, 50 per cent of such cases were linked to “risky drinking,” a level between moderate and heavy consumption, the study found.

Drinking 3.5 drinks a day can double or even triple the risk of developing cancer in the pharynx, larynx, mouth, and esophagus, says the Canadian Cancer Society.

StatsCan also found alcohol sales rose across the country by 4.2% in 2020 from the year prior; the largest sales increase in more than a decade.

And yet, only around 25 per cent of Canadian drinkers are aware that alcohol can cause cancer, according to the Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research (CISUR).

“There isn’t any health warning so the implicit assumption is that it can’t be serious or bad enough, or surely the government would require it – and they don’t,” said Dr. Tim Stockwell, a scientist at CISUR and professor at the University of Victoria’s psychology department.

Tracy Durant, a 44-year old business owner in Prescott, Ont. who said she occasionally drinks alcohol, said she was not aware of the link between alcohol and cancer, even though she has taken a course with Ontario Smart Serve, a non-profit organization which provides training on responsible alcohol service.

“I think we’ve been left in the dark about this.”

If any other substances carried such a cancer risk, the government would be doing more to warn Canadians, she said, noting that governments profit from hefty taxes on alcohol sales.

“There’s so much money being made off tobacco and alcohol; they forget or don’t want to tell us the side effects or the long-term side effects that these could cause,” she said.

It’s time for that to change, Stockwell says. He and a growing chorus of medical experts and advocacy groups such as the Canadian Liver Foundation, are urging the government to impose warning labels on alcohol products, similar to those required on cigarette packages.

The need for warning labels is more urgent because Canadians have increasingly turned to alcohol to take the edge off of the pandemic stresses during the past two years, advocates say.

One in four Canadians say they increased their drinking in January 2021 compared to the pre-pandemic period, according to a Statistics Canada survey. In 2020, the first year of the pandemic, alcohol sales across the country rose by 4.2 per cent from the previous year – the largest sales increase in over a decade, another StatsCan study found.

Patricia Barrett-Robillard, a cancer coach for the Ottawa Regional Cancer Foundation Centre, said she’s worried about the rise in alcohol use.

“That’s going to be a problem. That will have an impact on us because you would assume that we’ll see more clients,” said Barrett-Robillard, who aids past and present cancer patients to cope with their diagnoses and make plans to move forward.

While all cancers are difficult, alcohol-related cancers are often the kinds that the health care system does not have effective treatments for, such as stomach and esophageal cancer, she added.

Adding alcohol warning labels (AWLs) is one of the most effective ways of getting the word out about these risks, said Stockwell.

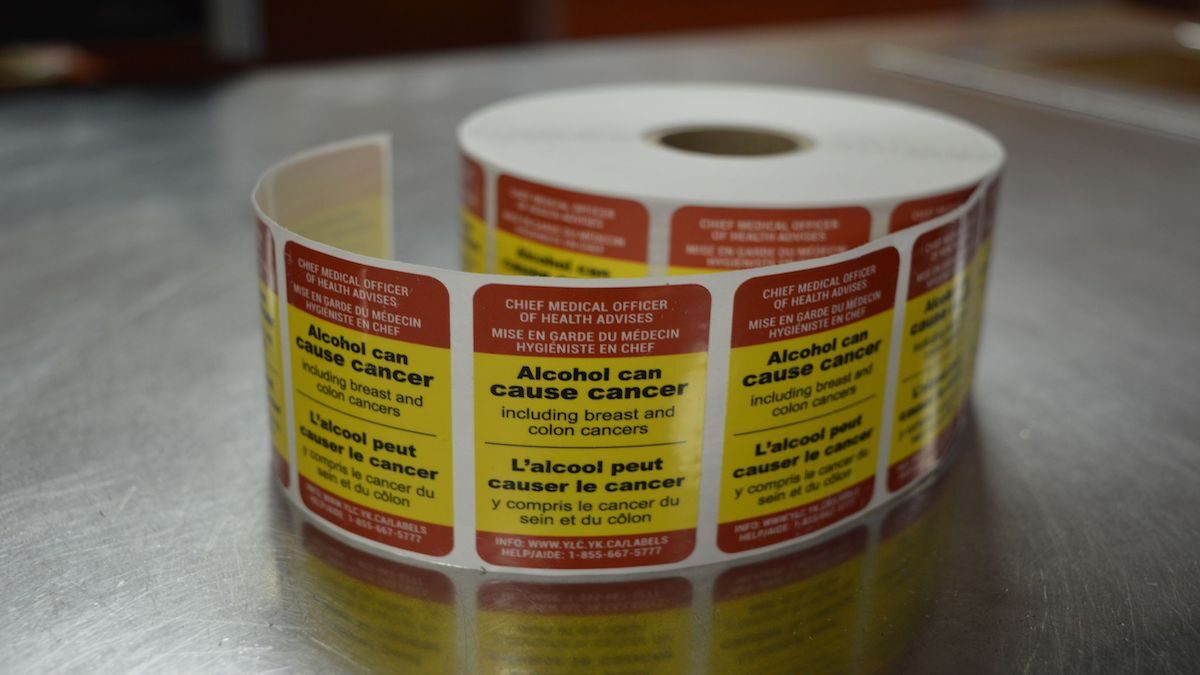

In 2017, with approval from the Yukon government, Stockwell and a team of researchers introduced warning labels on alcoholic beverages. They tested the labels at a large government-owned liquor store in Whitehorse.

The month-long study found that more than three-quarters of consumers weren’t aware of alcohol’s link to cancer. It also found sales decreased by around six per cent after the labels were added.

Stockwell said labels are easily the best option for their simplicity and cost-efficiency.

“It’s totally viable. There are health warnings on products all over the world. It’s one of the most cost-effective ways of communicating information,” he said.

AWLs are highly effective because it is the heavy drinkers – the group most at risk – who will see them most often, Stockwell said.

“This will reach the people who need the message the most. The more you drink, the more you see the messages. There’s kind of a perfect strategy (with AWLs) and I think almost anything else pales into insignificance,” he said.

Stockwell is not alone in his call to action.

Warning labels

Eric Dumschat, a legal director for Mothers Against Drunk Driving Canada (MADD), an advocacy group that campaigns against impaired driving, explained that these warning labels would be extremely helpful in spreading awareness of the risks associated with alcohol.

MADD supports mandatory warning labels, saying it is the government’s responsibility to provide information about health and safety risks of over-consumption, such as the posting clear information on serving sizes and standard drink sizes, Dumschat said.

Though current alcoholic containers include information on what a serving size of their beverage is, they do not post the recommended serving size laid out in government guidelines.

Moreover, government rules for alcohol labelling should, “be consistent with labels required for cannabis products,” Dumschat said.

Health Canada requires all cannabis products to carry labels warning about the potential health risks and effects of using cannabis.

The first health warning for cannabis listed by Health Canada is its link to toxins and cancer.

“WARNING: The smoke from cannabis is harmful. Toxic and carcinogenic chemicals found in tobacco smoke such as polyaromatic hydrocarbons aromatic amines, and N-heterocyclics are also found in cannabis smoke,” the warning reads.

Dr. Eric M. Yoshida, one of the board members of the Canadian Liver Foundation, also passionately advocates for mandatory AWLs.

Yoshida authored an editorial on the link between alcohol and cancer for the Canadian Liver Journal last spring.

Referring to Stockwell’s project in Yukon, his editorial urged the government to impose warning labels, noting that the Yukon study found that, “labels also increased awareness of and conversations about alcohol-related health effects and decreased consumption.”

If warning labels are such an easy answer, why aren’t they being used?

Lack of awareness

“I think it’s a lack of awareness (of the health risks) generally, and the industry working very hard to keep us all in the dark,” Stockwell said.

Stockwell was speaking from experience: the Yukon government shut down his warning-label project a month into the planned eight-month study period, after Canadian alcohol industry associations and local companies objected and threatened legal action, arguing that the labels were misleading.

Similar scenarios have played out in other countries. For example, the Commonwealth of Independent States, which encompasses nine formerly Soviet countries, including Russia, the European Union and Thailand have all tried to add health warnings to alcohol containers; however, because of industry pushback, they have failed to implement legal requirements, according to the WHO.

The WHO highly recommends that countries begin labelling alcoholic beverages to increase awareness of the risks.

Jan Wescott, the president and CEO of Spirits Canada, the national trade organization representing spirits manufacturers, said he agrees Canadians should be aware of the dangers of alcohol – but warning labels are not the answer.

“The issue is knowing your own health circumstances and getting advice from your own physician as to what is the best for you,” Westcott said.

Adding labels to every container of alcohol would be very costly for producers, he said. Instead, Westcott recommended measures such as lowering the standard drinking guidelines or using signs and QR codes in liquor stores linking to information about the dangers of excessive consumption.

Canada’s guidelines for low-risk consumption, last issued in 2011, are being revised: the Canadian Centre for Substance Abuse and Addiction, which produces guidelines with funding from Health Canada, is expected to issue updated guidelines this fall.

“We were big advocates of introducing the lower drinking guidelines. As a supplier, I want to be able to say to you as my customer, ‘What is the way you can use our products with the least risks to yourself?’ ”

Wescott says the industry is not seeking to push high alcohol consumption; rather, it wants to ensure all consumers drink safely, and only if they believe it won’t negatively impact their health.

The members of Spirits Canada have a responsibility to inform people about their products, and the appropriate ways to use them, he said.

“I’ve been arguing for quite a long time that we have a vested interest, a business-vested interest, in making sure people use our products properly, and that means drinking moderately, that means there are times when you shouldn’t drink.”

Jan Wescott, the president and CEO of Spirits Canada

“I’ve been arguing for quite a long time that we have a vested interest, a business-vested interest, in making sure people use our products properly, and that means drinking moderately, that means there are times when you shouldn’t drink.”

Westcott said he believes the vast majority of people who work in the alcohol business understand this.

“We have a responsibility to make sure that we’re being honest in that relationship and that means giving you information,” Westcott said. “So we’re not opposed to providing that information. We obviously think the information has to be legitimate; it has to be balanced.”

Warning labels such as the one in Stockwell’s study – which said, “Alcohol can cause cancer, including breast and colon cancers” – can be misleading, Westcott said.

“The inference being made is that if you drink at all, you’re going to get cancer. I think we need to be a little clearer with people,” he argued, saying that most of those being diagnosed with alcohol-related cancers are heavy drinkers.

There are better ways of conveying information about health risks and singling out the risk of cancer is questionable and needlessly frightening for consumers, he said.

He cited the example of Quebec’s Éduc’alcool’s program, which is funded by the Sociétés des alcools du Québec (SAQs) and provides programs to promote moderation and to educate consumers about alcohol consumption.

Would consumers actually pay attention to AWLs, or QR codes in liquor stores?

Gabriel Rivamonte is skeptical about the effectiveness of either approach over the long term.

“When people go to the LCBO, they already know what they want,” said Rivamonte, who worked at the Liquor Control Board of Ontario (LCBO) in Ajax for eight years, before changing careers in late 2022.

Though he was surprised about the link between alcohol consumption and cancer, Rivamonte said that over time, customers would probably just ignore labels and other health warnings.

Durant agreed that customers would eventually turn a blind eye to warning labels.

“Unfortunately, I think that eventually it would probably get ignored, because alcohol can be an addiction at the end of the day, and sometimes we tend to ignore the importance of our health,” Durant said.

“If we’re relying on the source (of alcohol sales) to get information out there, I don’t think it will be available to people.”

tracy durant, Prescott, Ont. businessperson

Rivamonte is also skeptical that provincial governments would get behind the push for warning labels, pointing to the tax revenues they recap from alcohol sales. In 2021, Ontario collected almost $2.4 billion from LCBO outlets, according to the agency’s annual report.

“They have a piece of that pie, so… they don’t want to hinder sales. But I would hope that they could have some sort of message out there.” Rivamonte said.

Durant agreed that there is a conflict of interest.

“If we’re relying on the source (of alcohol sales) to get information out there, I don’t think it will be available to people,” she said.

In an email response to a query about warning labels, a spokesperson for LCBO left the responsibility of labelling to Health Canada, and said, “through our Spirit of Sustainability social impact platform, the LCBO is committed to protecting the health and well-being of Ontarians by ensuring our products are safe and of the highest quality.”

While provincial liquor control boards may not be bullish about warning labels, the decision ultimately lies with the federal government. Labelling of beverage alcohol is regulated by the Canadian Food Inspection Agency in accordance with Health Canada rules.

More information needed

A spokesperson for Health Canada said the department recognizes the significant health risks associated with alcohol consumption, including various forms of cancer.

“Health Canada is aware of the growing calls for effective policy interventions to reduce alcohol-related harms in Canada,” the department’s media office said in an email.

Would stark warning labels about the risk of cancers associated with alcohol make a difference?

People may disagree about the best way to get the word out, but one thing is certain, according to Stockwell: Canadians urgently need more information about the cancer risks associated with alcohol use.

“We all have strong views…but at least giving the people the information to make their own choice – that’s on its own enough,” to make a difference, he said.