MONTREAL — Carleton University is moving forward with a plan to change the names of three campus buildings. The “New Names for New Times” initiative is an attempt to reflect diversity and inclusion on campus.

The University Centre, Residence Commons and Robertson Hall will get new names to represent the Algonquin Nation, Black communities, and Inuit respectively. Robertson Hall is the only building to get a new name after having been named for an individual. When the university announced the changes, its statement made no mention of Gordon Robertson, former Clerk of the Privy Council and chancellor to the university. Nor did it explain why the name of this building “was chosen to acknowledge and honour the Inuit.” Robertson will still be remembered with a plaque near the renamed building.

Carleton offered more information in a statement to Capital Current, saying:

“At Carleton, as on many university campuses across the country, over 40 per cent of our students are from culturally diverse communities. At all institutions, there is a recognition of the urgent need to better reflect our diversity in our academic mission and campus operations. Carleton has been at the forefront of change, notably in responding to the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, and must continue to lead the way towards a more equitable world where everyone can fully belong and fully contribute.

“Carleton has chosen three main campus buildings to receive New Names that reflect our diversity and commitment to inclusion. Our central administration building, currently named Robertson Hall, was chosen to acknowledge and honour the Inuit. We will begin consulting with Inuit groups, including the very large urban Inuit community in southern Canada, in the next several weeks.

“We will begin consulting with Inuit groups, including the very large urban Inuit community in southern Canada, in the next several weeks.” The university did not explain why this building was being renamed.

Aliqa Illauq, a Carleton student from Kangiqtugaapik, in the Qikiqtaaluk Region, of Nunavut, says the university did not properly represent Inuit nor did it explain the history of Gordon Robertson. “Every time you’re going to say Inuit, you never put a ‘the’ in front of it,” she says. “There are no Inuit ‘groups.’ Even in the circumpolar, Inuit were actually one.”

Gordon Robertson was one of the architects of the High Arctic Relocation program in which about 90 Inuit were sent two communities, Grise Fjord and Resolute Bay, in Canada’s High Arctic between 1953 and 1955. This happened at the height of the Cold War with the Soviet Union and while conflict was just ending on the Korean Peninsula. The idea was to better establish sovereignty over the islands of the Canadian Arctic.

Robertson, who died in 2013, began his career in the Department of External Affairs before becoming the deputy minister of the Department of Northern Affairs and National Resources and commissioner for the Northwest Territories, a position he held from 1953 to 1963. He reached the pinnacle of the federal public service in 1963 when he was appointed Clerk of the Privy Council and Secretary to the Cabinet by then prime minister Lester Pearson. He served in the post until 1975, when then prime minister Pierre Trudeau put him at the forefront of the constitutional file as Secretary to the Cabinet for Federal-Provincial Relations in the lead up to the first Quebec referendum on sovereignty. He retired from government in 1979.

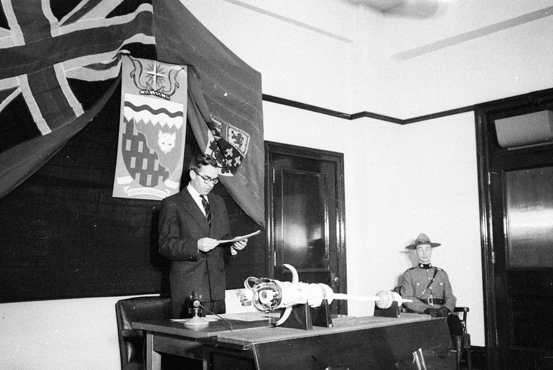

Gordon Robertson is seen here delivering a speech as territorial commissioner behind a desk on which the ceremonial mace of the Northwest Territories is lying. (Library and Archives Canada: Credit: Rosemary Gilliat Eaton).

A year later, he became chancellor of Carleton University where he remained until 1990. In addition to Robertson Hall, there is also a scholarship to the university for Inuit students bearing his name.

The federal government in 1953 promised Inuit families there would be abundant food in their new homes and only a short stay in communities much further north than they had been living. Inuit who were relocated instead faced desolate living conditions, a lack of game and no indication of when they might return home.

“With Inuit relocation, you talk to anybody in Canada, they’re going to say that it never happened. Especially 10 years ago,” Illauq says.

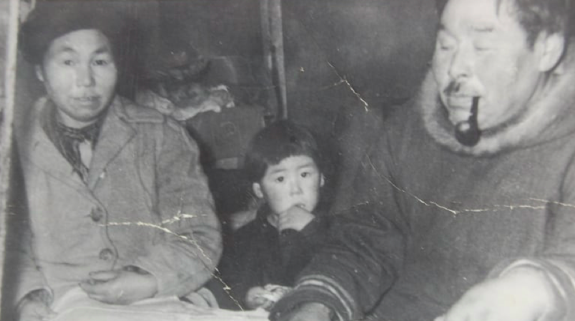

Larry Audlaluk, 70, an Inuk man and proud Canadian, was relocated to Grise Fjord, at the southern tip of Ellesmere Island, with his mother and father when he was two. A “self-proclaimed historian” and hunter, he says “for many Canadians, we are still the means of how they can get something out of being in the north.”

Audlaluk lost his father who died within a year of arriving to Grise Fjord.

As far as he is concerned, “Gordon Robertson was the old colonial where they made a promise and they broke it,” Audlaluk says.

Patrizia Gentile is a professor of human rights and women’s and gender studies at Carleton. When the topic of Indigenous sovereignty came up in her class last year, she was approached by Aliqa Illauq and told about issues around the relocation and Arctic sovereignty.

“If it wasn’t for her being in my class, we would not be at this point,” Gentile says. “I had to redo my entire lecture because I was taught something new that day that I needed to convey.”

“She was listening so much that she changed gears in her class to start talking about these lived realities and these experiences,” Illauq says.

In the following class, Gentile talked about Robertson’s role in the relocation. Gentile also encouraged her students to take action. Three – Emily Scott, Mackenzie Dawson, and Nadeea Rahim – who all sat in different corners of the class during the Winter 2020 term, connected over the issue. Together, they started a petition in June 2020 demanding a new name for Robertson Hall. The petition collected more than 800 signatures.

Four Carleton students were involved in a petition demanding a name change for Robertson Hall: They are Emily Scott (top left), Mackenzie Dawson (top right), interviewer Sarah Pledge Dickson (top centre), Nadeea Rahim (bottom left) and Aliqa Illauq (bottom right). [Screen Capture from Feb. 28 @ Sarah Pledge Dickson]

“They [the university] were sending all these emails about equality but they weren’t really doing that groundwork change,” Dawson said.

“The idea for the petition came as a way to pressure the university to make sure that there’s action behind those words,” Scott said.

With the resurgence of protests and demands for changes to policing and against systemic racism following the death of George Floyd in the United states and a growing push for the removal of monuments and names associated with racial injustice, “it seemed like it was time to try and make a change,” Rahim says.

Gentile connected them with Illauq.

“I’m humbled by students like Emily, Nadeea, Mackenzie and Aliqa, and their power. Having the initiative and the motivation to do this is really incredible,” Gentile says.

The four students approached the university in the fall of 2020 with their petition, the history they had learned and their suggestions. After being a part of initial communications, they have heard very little else from the school.

The university statement doesn’t mention the students nor their petition. “The first reaction I had was, where are the students who actually created this initiative? Where are their names? This is not something that they [the university] thought of,” Gentile says.

Despite that, the announcement of the name change was a welcome surprise for Dawson, Rahim and Scott.

“It was exciting to see that the name change was happening and that our efforts did actually mean something,” Rahim says.

But the statement still missed some of their recommendations. “As part of the end goal, we want there to be education, we want people to know the truth, because that’s really powerful,” Scott says.

“Out of all three buildings being changed, the most politically charged one was Robertson Hall,” Rahim says. “Why are you doing that? We know why but you’re not telling anyone else why.”

It wasn’t until the day before that Illauq was told the name would change, information she passed onto the rest of the team.

Illauq encouraged the university to bring the surviving Robertson family members into the conversation as well. Despite wanting to be a part of that conversation, she never was. A letter she wrote was sent by the university to the Robertson family. It was after that letter was sent that the family agreed to the name change.

“Especially talking about their father and the things that he may have done, they still listened,” she says.

Alan R. Marcus, a cultural historian and professor of film and visual culture at the University of Aberdeen, Scotland, travelled to Grise Fjord in the 1980s while working on a book about the resettlement called Relocating Eden. He interviewed Larry Audlaluk and Gordon Robertson extensively for the novel.

“There is the need to acknowledge the baggage associated with some of these former associations,” Marcus says.

“It is very important when you do anything with anyone, that it comes from a place of love and on equal ground,” Illauq says. “I am sure if this individual knew the rippling effects that his actions were going to cause, I am certain he would not have done it.”