Ski resorts in Ontario, Quebec and the U.S. northeast face a bleak future, with studies suggesting that many will no longer be viable by the year 2080. The reports have some local operators saying they are doing what they can to diversify and to maintain a low carbon footprint.

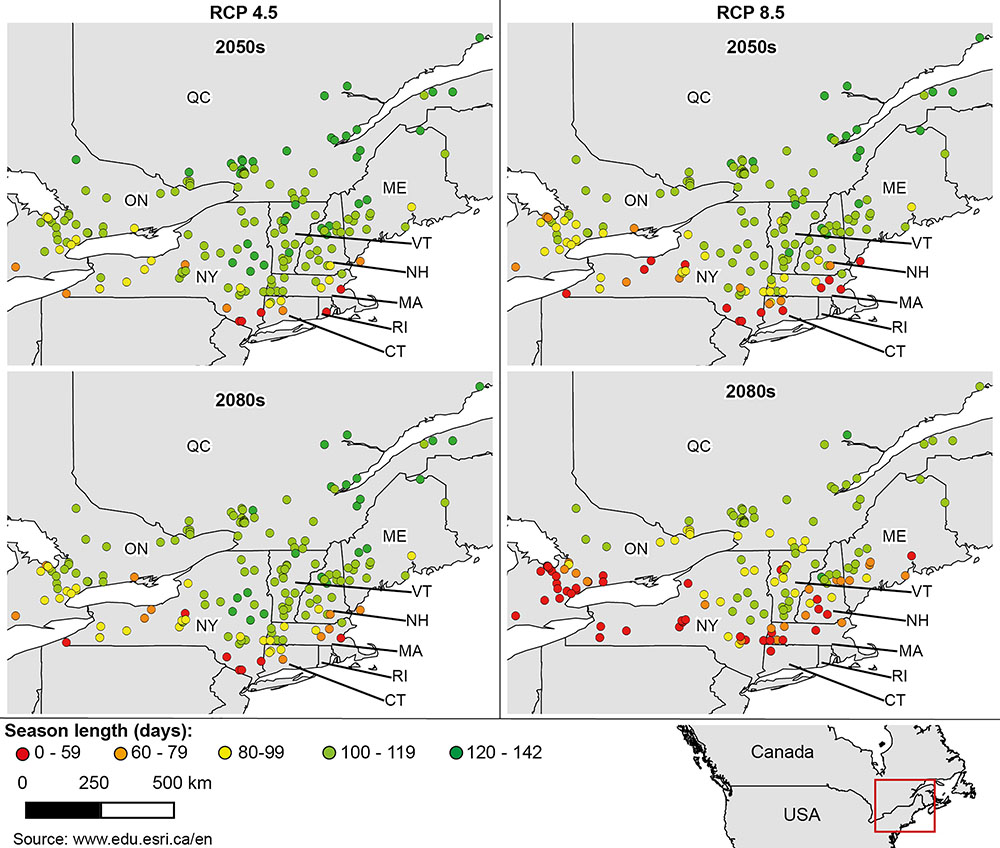

A 2019 study published in the Journal of Sustainable Tourism examined the economic viability of ski resorts under two different scenarios: a low-emission (called RCP 4.5) and a high-emission (RCP 8.5). Even under the low-emission scenario, researchers estimate that only 15 per cent of Ontario ski resorts will be economically viable by the 2050s.

Skiing is a popular sport and a livelihood for many people, but also a source of economic growth for some communities. According to the Canadian Ski Council, skiing-related revenues in 2016/17 were $178 million in Ontario and $295 million in Quebec.

Daniel Scott, the chair of the University of Waterloo’s Master of Climate Change program and one of the co-authors of the 2019 study, says ski hills in eastern Canada and the U.S. will have to adapt to a warmer climate.

“For Ontario we get a lot of lake-effect snow, but that can also come as lake-effect rain, which both prevents you from making snow and also washes away the snow that you had,” said Scott.

Research from the University of Waterloo explains that the hardest-hit regions in Canada will be Ontario and Quebec.

“Quebec is further inland, away from the Atlantic and the Great Lakes, slightly higher altitude and latitude, with colder winters, so they [Quebec] will fare much better than Ontario,” said Scott.

Ski resort operators say they are already seeing a big change in recent years.

“Each year [snow] comes later and later,” said Nathalie Dandoy, manager of environment and sustainability at Mont-Tremblant.

“We are used to opening the ski season around Nov. 20, but each year, we have difficulties because of the lack of snow, and also because of the too high temperatures that do not allow us to start the snow cannons,” she said.

While the resort has put a focus on more sustainable practices, include recycling, composting and reducing greenhouse gas emissions, Dandoy says that a later start to the season is just one of the challenges.

“We have more and more torrential rain events,” she said.

“That is really bad for all our mountain hiking trails, and the erosion forces our teams to do more repairs.”

“It’s not nice for the hikers, for our employees and for our finances, so we trained our teams to adapt their maintenance techniques and new ways to build trails.”

Dandoy says she is hopeful that more sustainable operations can at least make a dent in larger efforts to slow climate change.

“If ski hills start adopting sustainable practices now, they will find new ways to reduce our impact on the climate.”

Operators at Camp Fortune say they have been investing in year-round activities, because the ski season has become too unstable and more challenging to generate money from.

“The impact of climate change is top of mind,” said Erin Boucher, assistant director of marketing at Camp Fortune.

“We have expanded our summer activities to offset the winter season if it’s bad,” she said.

Over the years Camp Fortune has developed ziplines, mountain biking trails and a “mountain coaster” for non-winter tourist activities.

Ski resorts are also trying to operate in more sustainable ways, such as reusing water for snow-making.

“Most ski areas in Ontario and Quebec will have built a designated reservoir at the bottom of the ski hill, and they use that for their snow-making,” said Scott.

Ski hills typically fill their reservoirs with water in spring when they have spring runoff; come winter, that water is used to make snow.

“Eighty to 90 per cent of that water gets recycled into the same reservoir each spring,” said Scott.

Since the pace of climate change depends mostly on factors far beyond the control of ski hill operators, they will be relying upon global climate action for their long-term viability. In the meantime, Scott worries that skiing will become increasingly a more exclusive and expensive sport.

![Kendra Adams and Jackson McCully sit in their home in Gatineau with full winter gear on. The couple turn down the heat during the day to save money. [Capital Current Zoom screen capture]](https://capitalcurrent.ca/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/rent-250x144.png)