Col. John By is credited with the founding of Ottawa 196 years ago.

Our city was named Bytown then in honour of the British engineer who led the construction of the Rideau Canal.

On Monday, the community marked Col. By Day in memory of those who built the Canal.

On the other side of the Ottawa River, diggers found a small piece of Indigenous pottery and a stone tool contributing to a history that predates Ottawa by more than 1,000 years.

“The past in this area is rich,” said Ian Badgley, an archeologist at the National Capital Commission.

“We’re going to celebrate Col. By, but how about people that were here before Col. By?” Badgley said.

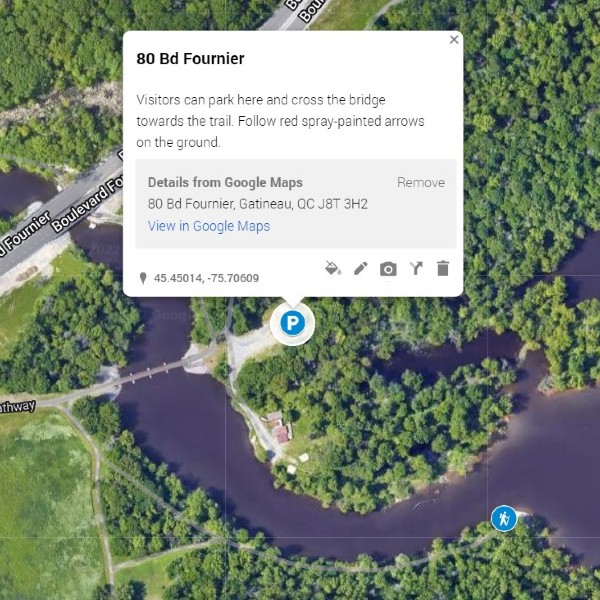

Badgley and the National Capital Commission hosted the first of its annual public archeological digs, that mainly have taken place at Leamy Lake Park in Gatineau since 2014. This year’s digs take place Aug. 1 to 3, Aug. 6 to 9, Aug. 13 to 15 and Aug. 27 to 30.

Visitors took a trail to the side of the Ottawa River and dug in marked areas across from Rideau Falls, located beside the National Research Council headquarters and the French Embassy.

Badgley said he’s taken Ottawa River boat tours to hear how guides present the area.

“They talk about buildings. There’s 24 Sussex. There’s the Papal Nunciature,” Badgley said. “I said, ‘You know, all along that shore, you’ve got 6,000 years of history.’ ”

The area where the Rideau and Gatineau Rivers join the Ottawa was a meeting ground, Badgley told Capital Current. There’s evidence of Indigenous traders from Hudson Bay, Labrador, Kentucky and Illinois, he said.

“The Ottawa River’s a highway for everybody,” Badgley said.

The NCC started the Assessment and Rescue of Archaeological Legacy project in 2018 to dig in areas that are increasingly eroding, Badgley said.

Diggers have found more than 85,000 pieces at the Leamy Lake site since then, he said.

“We’re all alone and we can’t do it ourselves, so we get the public to help and maybe they’ll learn a little more about the past here,” Badgley said.

Archeology is a chance to learn pre-settler history, said Drew Tenasco of Kitigan Zibi Anishinabeg First Nation.

“Whenever we dig up stuff, I’m seeing the tools that were made – the traditions that were had,” Tenasco said. “It just shows how our ancestors were living back then, which is something I never even knew about.”

“And that our people were very smart people,” added Jennifer Tenasco, also of Kitigan Zibi.

Take the way Indigenous peoples constructed tools, for example.

“Tools are made from previous tools,” said Kyle Sarazin of the Algonquins of Pikwakanagan First Nation. “A tool could start out as a point, like an arrowhead, and then it breaks somehow, and then they turn that into a scraper.”

Sarazin, Drew Tenasco and Jennifer Tenasco are summer students with the Anishinabe Odjibikan Andwanikesiwag, an archeological field school where they dig in four sites in the land where Ottawa-Gatineau exists today.

Anishinabe Odjbikan means “Anishinabeg roots,” said Jennifer Tenasco.

The students said they’re grateful for the opportunity to work on the site.

“I know when we speak to our grandmother, she’s always like, ‘I wish I had that opportunity when I was young,’ ” Jennifer Tenasco said.

“We’re the ones who are uncovering history,” Drew Tenasco said.

As Ottawa marks Col. By Day, Sarazin says he believes the day can serve multiple purposes.

“I think it could also be a day besides Ottawa celebrating its history,” Sarazin said. “It could also be a day of reflection of the consequences of making the Canal — how it’s changed the water and the surrounding area, either for good or for bad.”

A ceremony at the Rideau Canal Celtic Cross remembers the Irish workers and their family members who died while helping to build the canal, which was finished in 1832. “Not only Irish of course – the French, English, Scots and Welsh, and the Anishinabe as well,” said John Boylan, deputy head of mission to the Irish Embassy.

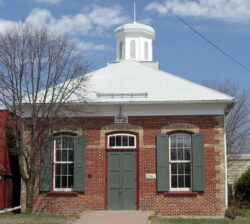

Three people placed the Irish, Canadian and Ottawa flags beside the cross. Bagpipe player Bethany Bisaillion led a procession from the Bytown Museum, across one of the lock gates that help boats avoid the rapids on the Rideau River, and towards the cross to the tune of “The Maple Leaf Forever”.

Ellen MacIsaac sang the Canadian and Irish national anthems as the audience faced the cross.

“What I see are the hard-working, the honest people who came here looking to make a better life for themselves and their families,” Boylan said.

The canal “was originally to protect us from the United States and invasion, and then eventually became a commerce transportation corridor,” said Ottawa Mayor Jim Watson. “Now as we see by that big boat over there, it’s a great tourist attraction.”

“There’s also great pride in knowing that my ancestors played a major role in building the canal,” said Sean Kealey, president of the Irish Society of the National Capital Region. “Learning the history that brought them here and allowed them to settle in the area has been eye-opening for me and I’ve tried to pass this information on.”

“It’s very important to never forget where we came from,” Kealey said.