Underwater structures made of materials as diverse as felled trees, tires, sunken ships or even 3D-printed ceramics could help conserve aquatic life and protect coastlines.

In early November, Dr. Helen Fox was scuba diving off the coast of Tulamben in Bali, Indonesia.

Amid patches of coral and rubble, Fox, who is the conservation science director for the Coral Reef Alliance, swam by statues of Hindu gods and temples as well as piles of tires. These objects were not thrown haphazardly into the ocean but were instead intentionally placed five to 10 metres underwater to boost reef recovery and tourism.

It was part of an effort by the Indonesian government to improve the livelihoods of communities affected by the COVID-19 pandemic through reef rehabilitation work.

The result was uneven. While some of the statues were growing coral, the old tires were not, most likely because they have a toxic effect on marine life.

“It reminded me of what amazing ecosystems (reefs) are, how threatened they are and really how much we humans need to do to step up our efforts to tackle climate change — that’s going to be a big collective effort — and a lot of the other threats of coral reefs,” said Dr. Fox.

The statues are just some of the many materials trialed as artificial reef scaffolds.

Around the world, conservation scientists are also testing 3D-printed ceramics, concrete and even felled trees.

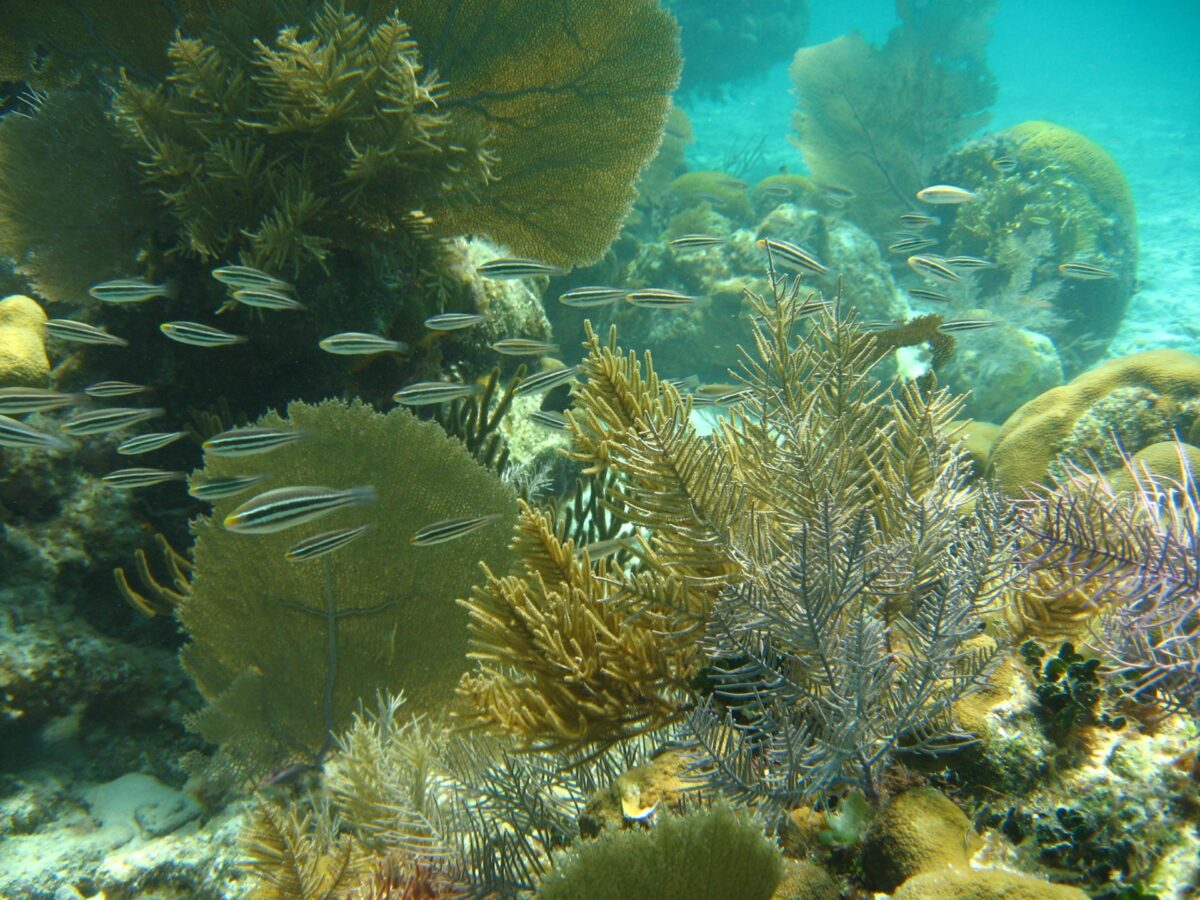

Researchers use them to simulate the complexity of natural reefs and to serve a variety of purposes, including maintaining coastal habitats, hosting aquaculture, providing eco-tourism opportunities and conserving biodiversity.

The hope is that as global warming accelerates the destruction of reefs, these artificial reefs may act as a stopgap to help preserve marine life.

By the end of this century, scientists predict that 99 per cent of coral reefs will collapse without concerted efforts to protect them. Even if global temperatures are kept at 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels, 70 to 90 per cent of the world’s reefs are still expected to disappear. These estimates do not account for the loss of reefs formed by marine organisms, such as shellfish.

The idea to submerge structures to create artificial underwater environments may date as far back as the Neolithic period, but some of the first reports of installing artificial reefs in modern times began in the late 18th century, when Japanese fishers purposely sank bamboo structures with leaves to form fishing sites.

More recently artificial reefs aim to additionally help moderate ocean waves, and to maintain the breeding and survival of reef reliant marine creatures – the two primary roles reefs play in marine environments.

“I don’t think there’s really a material that is best or maybe worst for artificial reefs,” said Dr. Antony Jensen, an associate professor at the University of Southampton, England who helped develop the European Artificial Reef Research Network.

It all depends on the specific location.

In Europe, he said they have started implementing nature-based solutions that urge a move away from the traditional structures that existed only to be big and block waves or storms to structures that simultaneously absorb energy before it reaches the coastline and increase biodiversity.

These artificial reefs, multipurpose or otherwise, must be thought through and installed using sound engineering and conservation principles rather than happen as “an accident or something of convenience,” Jensen says.

“People wanting to dump rock, rocky waste or waste material from coastal quarries and things like that, they’re really keen to call this an artificial reef when really it’s just a convenient means of disposal,” said Dr. Jensen.

Dr. William Seaman is a professor emeritus for Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences at the University of Florida and author of the book Structure in the Sea, a deep dive into the field of artificial reef habitats and sea floor structure.

With the term ‘artificial reef’ used so broadly, Seaman prefers an alternative term, namely ‘purpose-built reefs,’ which are structures made of “either natural materials or man-made materials deployed on the seafloor to achieve some biological, economic, or engineering purpose.”

“Humans will never build a Great Barrier Reef out of concrete, steel, or sunken ships,” said Dr. Seaman. “But I’m more coming to the conclusion that [these materials can still] be very effective on a localized basis.”

Suppose these reefs are placed in marine protected areas, he explained. In that case, Dr. Seaman said the structures can possibly replenish fish stocks by becoming a spawning ground and supplying juvenile or larger fish in unprotected areas.

“I think that as you go around the world, there are very different philosophies about how the marine environment can be managed,” said Dr. Jensen.

Over in San Diego, at the Department of NanoEngineering at the University of California, Dr. Natalie Levy is part of a team developing new reef restoration and engineering tools.

In 2022, Dr. Natalie Levy collaborated with the University of Haifa and the Israel Institute of Technology to examine how 3D technologies could evolve the fabrication of artificial reefs as a reef reformation tool.

“I would say that my original research was on how to create an artificial reef that is as close to a natural reef as possible in the most holistic approach,” Dr. Levy wrote in an email.

With this goal in mind, she integrated real-time data – a mixture of environmental DNA with biodiversity and structural data captured through 3D imaging – from coral reefs to create a more biologically accurate foundation for the artificial reef.

A reef 3D-printed out of ceramic, which, while less affordable, contributes less CO2 emissions compared to less sustainable materials like concrete, she said.

Although she noted that concrete can still be useful for lower-income communities wanting to restore their coral reefs or to provide alternative fishing grounds.

Dr. Jon Dickson is a PhD candidate for the Department of Coastal Systems at the Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research in Den Hoorn, Netherlands. He led a study in 2022 that alternatively determined reefs designed to biodegrade and be settled by shellfish could also effectively and affordably enhance local marine biodiversity.

“Research on artificial reefs is extensive. It spans multiple jurisdictions and disciplines, but in terms of biodegradable artificial reefs, that is in its infancy,” said Dr. Dickson.

Dr. Dickson and his colleagues sunk 32 reefs made from felled pear trees to mimic reefs made from sunken driftwood in the Dutch Wadden Sea. Four months later, they surveyed the reefs on ships for organisms attached to the earthy material, and after another two months, they measured fish populations near the reefs through capture and release. They found that there were five times more individual fish caught across all reef blocks.

While these artificial reefs can kickstart biodiversity very quickly, Dr. Dickson said it still takes decades to accumulate the same biomass as mature reefs, especially with the threat of woodworms eating them in the ocean. This makes it essential to protect what little reefs are left out there to fight back against biodiversity decline, Dr. Dickson said.

“We can create all the new habitats we want, but if people keep harvesting them for economic gain, they will never mature,” said Dr. Dickson. “A mature reef is intrinsically more valuable than a new reef because species have been adapting to their local environmental conditions for decades, perhaps even centuries.”

Dr. Fox added that communities need to broadly ensure that there is good long-term monitoring, especially in the current funding climate that incentivizes quick reef restoration.

“It’s just sort of volume, not necessarily thinking about biodiversity or long-term sustainability,” said Dr. Fox.

Still, Dr. Fox said that while investing in this new research and development is important, a disproportionate amount of resources are going towards these projects compared to bigger-picture conservation efforts.

While helpful, artificial reefs are not a long-term solution but more of a stopgap that can benefit local communities, says Lauretta Burke, a retired geographer who led efforts on coral reefs within the Sustainable Ocean Initiative at the World Resources Institute. In 1998, she helped develop Reefs at Risk to raise awareness about the extent of threats to coral reefs worldwide. The report was later updated to provide a more high-resolution look into global threats, including the warming seas and ocean acidification.

If you haven’t alleviated the threats — particularly those under-recognized like sewage discharge — that cause a reef to decline in the first place, she says you will not be able to transplant “on a scale to offset the declining coral reefs that we’re currently experiencing.”

“There’s really a large scope for collective pressure to basically try to decarbonize the economy, which is big and complicated,” said Dr. Fox. “But again, there are a lot of solutions that are there already and it’s a matter of political will and financial and corporate incentives to do the right thing as opposed to keep on doing the wrong thing.”