As the pandemic surges through its second wave, health-care workers across Ontario are feeling more burned out than ever, according to survey data. But workers say high levels of stress and anxiety existed long before the pandemic and have only gotten worse since it started.

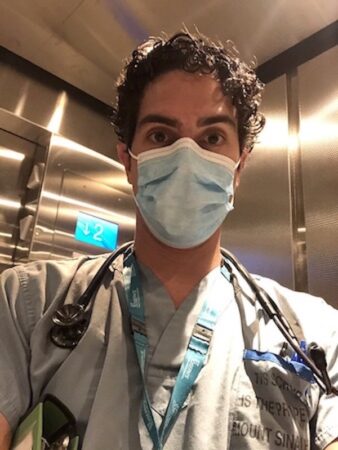

Nathan Stall, a staff geriatrician at Toronto’s Sinai Health System, said COVID-19 has created a period of more prolonged, chronic stress for health-care workers who increasingly feel left behind.

“The work is intense, cognitively, emotionally,” he said. “And it’s intense in terms of the gravity of the decisions that are being made and the knowledge that we are generating that is influencing decisions in real time.”

Stall added that what he sees as government inaction has only exacerbated that stress.

“We’ve had a lot of deaths and preventable deaths,” he said. “And we’re seeing now in jurisdictions … that decided to reopen, they started to continue to push forward with reopening even in the face of rising transmission and received the disaster that’s unfolding in provinces.”

A survey of 7,358 nurses conducted by the Canadian Federation of Nurses Unions found that nurses experienced high rates of burnout before the pandemic even hit. Reported symptoms included emotional exhaustion, depersonalization (feelings of cynicism and detachment), and a decreased sense of achievement and efficacy at work.

A large source of stress for health-care workers during the pandemic has been a lack of personal protective equipment (PPE). A different survey by CUPE found that of the 3,000 health-care workers who responded, 87 per cent felt they weren’t being provided adequate PPE and 91 per cent felt abandoned by the government of Ontario.

CUPE’s survey, which was released in March, prompted the Ontario Council of Hospital Unions to recruit researchers James Brophy and Margaret Keith to interview health-care workers about their personal experiences during the pandemic.

“What we heard was just this incredible anger and frustration and hurt that the health-care workers had, that they didn’t feel that their lives mattered enough, that they weren’t being protected,” said Keith.

While the study, Sacrificed: Ontario Healthcare Workers in the Time of COVID-19, is peer-reviewed, it only interviewed ten workers in the health system. But Brophy and Keith said health-care workers are afraid of the repercussions for speaking out. Some workers interviewed talked about being told they weren’t allowed to speak publicly about working conditions.

Most also expressed increased levels of stress and anxiety, and overwhelming workloads due to staff shortages.

“The sense of isolation, the fear that they could contaminate their loved ones” were factors, said Brophy. “Then of course, not seeing their grandchildren, not seeing their friends and family, and feeling stigmatized, feeling like they were a walking infection, which further isolated them and filled them with fear.”

Brophy added that some said their families would encourage them to relax, but they felt it was impossible to “leave work at work.”

“They would say, ‘We can’t; this is consuming us.’”

Peggy Larin, an x-ray technologist at Lakeridge Health in Ajax, Ont., said she fears passing the virus to an at-risk person.

"I haven't seen my elderly father in months."

For Larin, the lack of preparedness on the part of the government has been a source of stress that she says could have been avoided.

“Hospitals prepared after the 2003 SARS pandemic by making negative isolation rooms and new policies to be in place in case it ever happened again,” she said. “But in 2020 with the COVID-19 pandemic, it didn’t appear that we were ready for the volume [of cases] that we are currently encountering.”

Larin, who was working at Sunnybrook Hospital during SARS, added that burnout during SARS was primarily psychological due to the severity of the cases. COVID-19, however, has been more physically exhausting because of the volume of patients over a prolonged period.

For Stall, while the initial fear has waned for the most part, the frustration is mounting as resistance to public health measures continues in some quarters.

“There's always going to be people who protest and outwardly and cowardly betray what we are asking people to collectively do,” he said.

He added, “I didn't ask for the pot banging or food donations. The only thing I think most of us are asking for is for people to follow the public health guidance. That would be the best way to show us solidarity.”