When I talk to someone new about the sport I love, the sport that has shaped me as a person, I often catch myself saying, “It’s kind of like hockey.”

I’ve been playing ringette for 14 years, and I can confidently say the sport is much more than a hockey lookalike. And it’s a huge part of my life — a sporting passion that I appreciate more than ever after nearly two years of pandemic disruption, including the latest suspension of play — until at least Jan. 3 — announced on Dec. 18 by Ringette Ontario.

Ringette is played on an ice pad with five skaters— one centre, two forwards and two defence — and a goalie. The ultimate goal is to outscore the opposing team, and each goal is worth one point. Some ringette equipment also resembles hockey gear, such as helmets, neck guards, elbow pads, shin pads and, of course, skates. Growing up, I would always use my brother’s hockey hand-me-downs.

But ringette sticks don’t have blades, so we can stab the rubber ring we have instead of a puck. We wear girdles and ringette pants instead of hockey pants. And we will be thrown into the penalty box by the referee if we throw a hit because ringette is a non-contact sport.

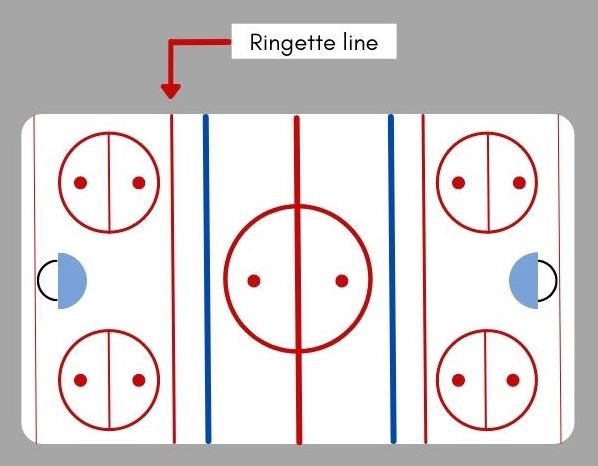

The rules of ringette differ extensively from hockey, as well. Players must stay out of the goalie’s crease, pass the ring over each blue line — but not both — and ensure only three players from each team skate past the ringette line.

Because of these rules, there is no off-side, allowing players to work together as a team. In fact, a player can’t skate the entire rink by themselves with the ring and try to score.

So ringette is not a one-player sport; the team works together to win. My boyfriend recently told me how strange it is that in ringette — as in hockey — we record the scorer and two assists on game sheets when a goal is scored. Even though it is rewarding to score a goal, in ringette you usually owe it to at least one other player.

The push for collaboration is not just part of the rules, it is the foundation and vitality of the sport itself.

14 years in the making

I’ve been playing ringette since I was seven years old. My mother often recalls how mesmerized she was by my skating. My parents first enrolled me in CanSkate, a skating program for beginners, when I was five.

I remember going to buy skates with my dad, who naturally — as a hockey player himself — wanted to suit me up in hockey skates. I, however, had something else in mind. I wanted pretty white figure skates.

During my first CanSkate session, my feet started hurting and everything just felt off. In the middle of the session, I got off the ice and started complaining to my dad. The next session, my dad suited me up in my brother’s old hockey skates. Stepping out onto the ice for the second time, I had instant relief.

One of the coaches at the sessions, who was also a figure skating instructor, reached out to my parents about enrolling me in private figure skating lessons because of my natural ability. But my parents politely refused because they wanted me to play a team sport.

A couple of years later, one of my mom’s best friends, someone she’d met the year I was born, invited us to watch her daughter’s ringette game. Her daughter, who was also one of my best friends, was playing for the Nepean Ravens. I still clearly remember her royal blue ringette pants.

I was mesmerized the entire game. Afterwards, my mother and I went to the team’s dressing room to listen to their coach speak. I was even given some oranges just like the rest of the players — a staple post-game snack. It made me feel as if I already belonged.

My mother later asked me what I thought about it all and if I wanted to try playing ringette, too. I instantly lit up and agreed. I’ve been in love with the game ever since.

I’ve played many sports — soccer, golf, volleyball, field hockey, cross country, track and field, basketball — but the dynamic of ringette has always been unmatched. Perhaps it’s because it is a female-oriented sport, which felt empowering, or the fact that it was invented in Canada.

The story behind ringette

Ringette was created in 1963 by Sam Jacks, who was elected as the president of the Society of Directors of Municipal Recreation of Ontario. He wanted to develop an on-ice game for women that encouraged movement and participation. The inspiration stemmed from his three sons — Barry, Bruce and Brian — who played hockey.

I remember meeting Jacks’ son, Brian, when I was in high school. He was at the Kanata Golf and Country Club, where my dad normally plays. As a competitive ringette player, I was starstruck and felt as if I was meeting a living part of ringette’s history.

It also put into perspective how new the sport still is. The game is still adjusting and is different now from when I was playing as a kid. Recently, some of my teammates and I were laughing about how someone used the term “tweens” to reference what is now called U14, the level for 13 year olds and younger. During my time, the levels were Bunnies, Novice, Petite, Tweens, Junior, Belle, Open and Masters. Now, we just say U9, U10, U12, U14, U16, U19, Open and Masters.

Though ringette is a sport anyone can join, inclusivity is still something Ringette Canada, the national sport organization, is working on. In June 2021, Ringette Canada updated its Transgender Inclusion Policy “to address gaps that excluded players who identify as transgender male or non-binary.”

Some organizations, including the association I used to play with as a child, the City of Ottawa Ringette Association, now have Ringette for All — a league for children who have varying levels of physical or cognitive abilities.

Kim Gurtler, the co-founder of Ringette for All, was a parent, trainer and assistant coach for several teams I played on as a child. I think this really speaks to the strong sense of community ringette fosters. Ringette, especially in Ottawa, is a pretty tight knit community. Everyone knows everyone. One of my best friends today is someone I met through ringette.

A game for life

I now play for Ottawa Avalanche, a team registered with the Gloucester & Area Adult Ringette Association, at the Open A level — one of the highest levels of adult ringette. I also coach and volunteer for CORA whenever I can; it’s so exciting to see young players fall in love with ringette.

Before the pandemic, my team was training for Open A provincials — we were ranked first in Ottawa and second in Ontario. But because of the pandemic, all ringette games and practices were cancelled. It was only in September, nearly two years since everything shut down, that my team returned to play for several months this fall.

Going so long without playing with my teammates, whom I see as my family, was extremely difficult. Many of us depend on ringette for not only our physical but mental health, so the switch to off was a very difficult adjustment.

Playing ringette under COVID-19 protocols has been different and remains unpredictable. During the fall, players had to complete symptom-screening questionnaires and show proof of vaccination before entering arenas. In the dressing room, we kept our masks on until we put on our helmets. We no longer shook hands with the opposing team after games; instead, we stood on our respective blue lines and tapped our sticks on the ice in a mutual show of sportsmanship.

The latest wave of COVID-19 has suspended play again, but hopefully ringette will resume early in the new year.

I can’t wait to walk into the dressing room, as smelly as it may be, to see the beaming faces of my teammates again. I look forward to the anticipation of stepping back out on the ice together, ready for action, inspired by an incredible coach.

Once the Omicron threat abates, we should be back in training for tournaments, league games and provincials. We’ll gather for practices when we can. And I’ll be happy, once more, to be reunited with the most wonderful group of women I’ve ever known.