Critics of the Ottawa Police Service’s strategy to reinvent the way it responds to mental health calls are urging a faster pace of reform and a greater role for community groups in shaping the policy.

And they intend to move forward within their own study of whether a version of a 30 year old program in Eugene, Ore., where mental health workers are deployed as the first contact for those in mental health crises, could be adopted here.

Many community members questioned how “community driven” the Ottawa Police strategy on mental health calls would really be at a Jan. 25 meeting of the police board. They also disputed a $13 million increase to the city’s police 2021 budget.

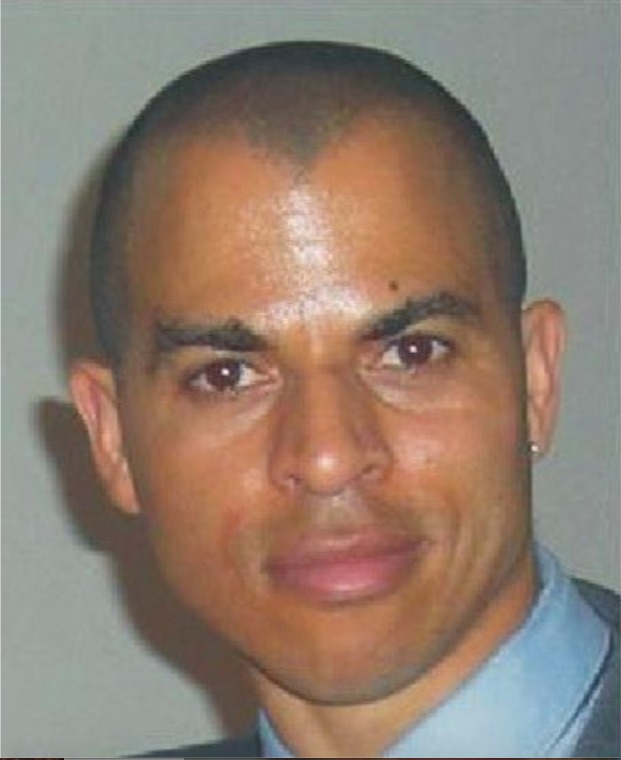

Robin Browne, co-founder of the advocacy group 613-819 Black Hub (the Hub), said he and other advocates are unhappy with the OPS’s approach to developing its new Mental Health Response Strategy.

“Despite the fact they keep saying they’re not going to lead, they clearly are. It’s the OPS strategy,” said Browne who mentioned a statement by the Ottawa Police Chief Peter Sloly that the city’s police service “cannot create, lead, or direct this effort on our own.”

Public consultations to help develop the Ottawa Police strategy will unfold over three years and that’s too slow for Browne and others.

“The three-year time frame is completely unacceptable when our people are continuing to be killed,” said Browne.

“COVID makes this even more urgent. We are fully expecting that there’s going to be a wave of people in mental health crises. COVID is having a massive impact on people’s mental health and — like everything else — disproportionately on Black people and Indigenous people.”

In October, the Ottawa Police Service Board held a meeting at which the proposed budget increase was first discussed and Sloly outlined the force’s plan to improve responses to mental health crises. This followed the acquittal of Ottawa Police Const. Daniel Montsion on charges of manslaughter, aggravated assault and assault with a weapon in the death of Abdirahman Abdi.

The OPS said with its new mental health response strategy, it will work collaboratively with mental health experts and members of the community with lived experience.

“The OPS will actively seek input and feedback to inform the design and implementation of this strategy,” it stated. “We will listen to the opinions and views of people in Ottawa — our partners, subject matter experts, people with lived experience, and the general public — and adapt our approach accordingly. We want all voices to be heard and a strategy to be created that both reflects and serves the diverse communities that make up our city, ultimately leading to better mental health outcomes.”

The OPS report also stated that: “In addition to ensuring that OPS officers receive training so that they are better-able to understand and respond appropriately to people in mental health crisis, our hope is that one of the long-term outcomes of this work will be that a fourth option is available to 911 dispatchers who receive mental health-related calls where a person is not in immediate danger. In these cases, a response by member of a specialized community mental health team — rather than OPS, OFD or paramedics — may be appropriate.”

But the OPS consultation plan does not satisfy Emma Bider.

She told the Board she and others were not impressed with the police approach.

“A lot of people were really dissatisfied generally with … the police trying to continue to be involved in mental health responses,” she said. “There was skepticism around the (promise of) police being ‘led’ by community members and by mental health partners.”

After the meeting, Bider expressed her doubts about the ability of the OPS to tackle mental health crises and domestic violence.

“(They) are things that in my opinion the police have proven over and over again they are not capable of handling,” she said.

Bider also argued that mental health professionals and agencies could provide these services rather than the police. “Those things aren’t being funded, but the police are,” she said.

Despite calls from public delegates and community members last fall to defund the police, the OPS received a net operating budget of $332.5 million, an increase of $13.2 million over 2020.

Browne and the Hub opposed the increase. “They should have frozen that budget and taken that $13 million and put a big chunk of it into public health,” he said.

All the research shows that putting money into social services will ultimately reduce crime, “because you’re addressing the social determinants of it,” he said.

Sloly — the first Black police chief in the history of the Ottawa force — disagrees with the idea of taking funding from the police and putting it towards social services. He has called it “irresponsible” and “dangerous.”

On Feb. 21, the police board meeting said the community-led mental health response strategy is a priority for 2021.

And the force said “(initiation of) dialogue and partnership work to develop new programs and tools that enhance service delivery to the community” was one of its accomplishments of 2020. The statement aslo acknowledged much work remains to be done.

Taking action

But The Hub is not waiting for the police. The organization is planning to fund an independent study to show what it would take to implement a program that would be similar to the CAHOOTS program in Eugene, Ore where mental health workers operate mobile treatement vans to respond and help those in need. The program has been running for 30 years and is funded by the Eugene police. “The study will show that it will be cheaper to send a medic and a social worker than a $70,000-a-year officer or two,” said Browne.

Sloly has not been convinced by the CAHOOTS program, saying that it took 30 years to get results.

Browne says that is “flat out untrue. The CAHOOTS program has been around for 30 years and has been getting results for 30 years.”

He also disputes Sloly’s belief that people in mental health crisis can become violent — and Browne referred to the CAHOOTS program as evidence.

In 2019, police backup in the Oregon city was requested 150 times out of about 24,000 CAHOOTS calls.

“We’re quite concerned about these narratives that are untrue first of all and they seem to be being used by the chief to slow the process down,” said Browne. “And again, that’s completely unacceptable when our people are literally being killed.”

Emma Bider on the Jan. 25 OPS Board meeting: