Until the federal government changes current drug policies, advocates say decriminalization — also a key goal — is not enough to reduce overdose deaths across the country.

Policy advisors and community organizations say B.C’s recent decriminalization of adult possession of up to 2.5 combined grams of select drugs is a positive step in destigmatizing drug use in Canada.

However, advocates say the country’s capital — like so many other cities — continues to face high levels of drug deaths because the Ontario government is not supporting harm reduction services financially, and the federal prohibition of many drugs allows a toxic drug supply to flourish.

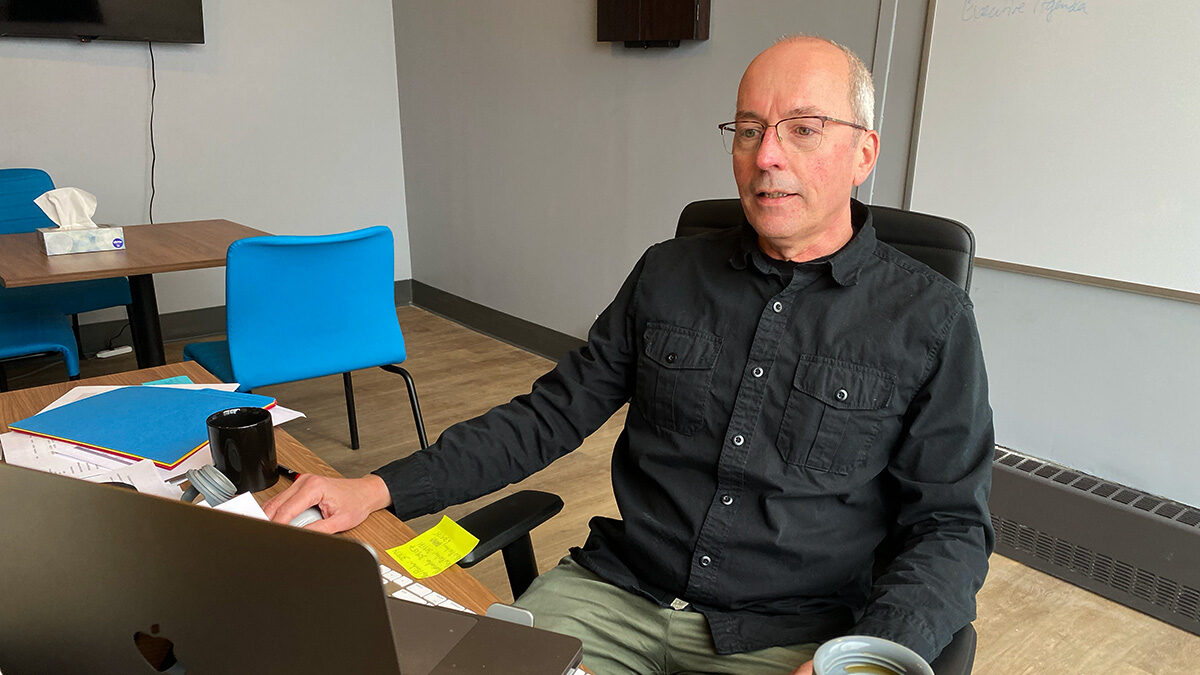

“Downstream, we’re pulling people from the river,” says Rob Boyd, CEO of Ottawa Inner City Health. “But we want to go upstream to see why people are dropping in the river in the first place. And what’s upstream is the drug policy.”

Canada’s Controlled Drugs and Substance Act prohibits the possession, trafficking, smuggling and production of many substances, including drugs such as cocaine, ketamine, opiates and methamphetamines. Section 56 grants exemptions if provinces appeal for flexibility in exceptional circumstances to safeguard people’s health, as B.C. has recently done.

According to Nicholas Boyce, senior policy analyst at the Canadian Drug Policy Coalition, Canada’s prohibitionist drug policies contribute to the overdose crisis.

“What we’re seeing on the streets are very volatile and toxic drugs, which is the direct result of prohibition,” Boyce said. “There is no regulation of the production of them.”

‘Downstream, we’re pulling people from the river. But we want to go upstream to see why people are dropping in the river in the first place. And what’s upstream is the drug policy.”

— Rob Boyd, CEO, Ottawa Inner City Health

Martha Jackman, a constitutional law professor at the University of Ottawa, wrote in a study published last March that decriminalizing drug possession is a constitutional imperative. In the paper titled “Protecting Health, Respecting Rights: Decriminalizing Drug Possession as a Constitutional Imperative,” posted online at SSRN (the Social Science Research Network), she found that criminalizing drug use and possession infringes Charter rights — specifically Section 7, the “right to life, liberty and security of the person.”

Many academics also find that Canada’s drug policies are rooted in racism.

“There’s no shortage of discussion and research, but what’s really lacking is the political will to move this issue forward,” says Jackman. “Many people are incarcerated or dead because of these policies.”

Jackman adds that the criminalization of most drugs also creates significant stigmas about drug use that prevent people who use them from seeking medical support.

‘There’s no shortage of discussion and research, but what’s really lacking is the political will to move this issue forward. Many people are incarcerated or dead because of these policies.’

— Martha Jackman, constitutional law professor, University of Ottawa

Boyd says the criminalization of drug use creates the stigma that people who use are bad. Since many individuals fear social alienation, they avoid telling their loved ones and their health-care services about their substance use or addiction.

Often, Boyd says the stigma makes individuals also feel judged by health-care providers, especially those who primarily refer patients to abstinence programs.

“There’s this popular idea that if we send someone off to detox or a drug rehab program when they come out the other side, they’ll be fixed,” Boyd says. “That’s simply not the case.”

He adds: “The drug is a small part of the individual. It’s more important to look at the circumstances around them.”

Though Ontario has seen an increase in harm reduction awareness and supports such as supervised consumption sites, the criminalization of drug use limits social- and community-based support.

“Everybody can get to a point where they’re stabilized, but having a criminal record is a life-long sentence,” Boyd says. “It follows you forever and impairs your recovery.”

The John Howard Society, which is working towards “effective, just and humane responses to crime and its causes,” says having a criminal record could hinder prospects for housing, employment and education.

Boyd and Boyce say decriminalization fails to address the toxic drug supply.

“Decriminalization doesn’t stop people from dying,” says Boyce.

Boyd says the federal government should decide, substance by substance, how to best regulate in a way that takes into account the varied forms and effects of drugs.

“We don’t want people to use fentanyl, but we also have to deal with the reality that there are people who are dependent on high-dose opioids,” he says.

Currently, there are several pilot programs across Ontario to address the toxic supply problem through community-based initiatives, but Boyd says Ontario Premier Doug Ford’s Progressive Conservative government is unsupportive of harm reduction services, despite the evidence backing this approach to saving lives.

One model for safer supply is the prescription of pharmaceutical-grade opioids, also called the Safer Opioid Supply (SOS) programs. This system can increase a substance user’s interaction with social health services while providing them with non-toxic opioids.

Since Canada’s first SOS program opened at London InterCommunity Health Centre in 2016, the country has seen an increase in similar sites. In 2020, Health Canada officially allocated federal funding for more SOS programs in Ontario.

“When people who use drugs know where the drug is coming from and that it’s a safe supply, we see all sorts of improvements in health,” Boyce says.

‘When people who use drugs know where the drug is coming from and that it’s a safe supply, we see all sorts of improvements in health.’

— Nicholas Boyce, senior policy analyst, Canadian Drug Policy Coalition

Researchers have found that Ontario’s safer opioid supply programs led to a significant decline in hospital admissions. However, Boyd says the model may not work for every individual, so there needs to be a variety of resources tailored to need.

He says these programs are still developing because they rely on funding through temporary research projects or the federal Substance Use and Addictions Program.

“We spend time and money on policing using drugs, but we have got our priorities mixed up in terms of where we’re putting our resources,” Boyce argues.

Boyd agrees. “We need to address the drug supply,” he says. “We’re not going to address it through border control or policing at the community level. We need to address it by providing a safe alternative market for people to access.”

He added: “We’re never going to eliminate the unregulated market, but we can certainly do a lot to shrink it.”

Supportive resources:

- Interactive map of supportive services across Canada

- ConnexOntario: connection to 24/7 mental health & addictions services

- How to use a Naloxone kit