My mom told me generations of Palestinian women learned the traditional stitching style known as tatreez from their mothers, who learned it from their mothers, who learned it from theirs.

Mother and daughter would sit together under an orange tree by the sea — at least in my mind — and learn the different patterns and what they all mean.

Unfortunately, my mom’s mom wasn’t taught tatreez. She was born in Lebanon, to a family of 14 who lived in a two-bedroom apartment with one bathroom. They were dirt poor, not even a generation removed from the Nakba — the dispossession of some 700,000 Palestinian people during the 1948 Palestine war — that stole their home from them.

My great-grandma had bigger things to worry about than teaching her daughters the traditional embroidery of our land.

Now, my grandma lives in Ottawa with us. She visited her homeland for the first time in the summer of 2019. She spent a week in Jerusalem and brought me back T-shirts, millions of photos and a small tatreez beginner kit.

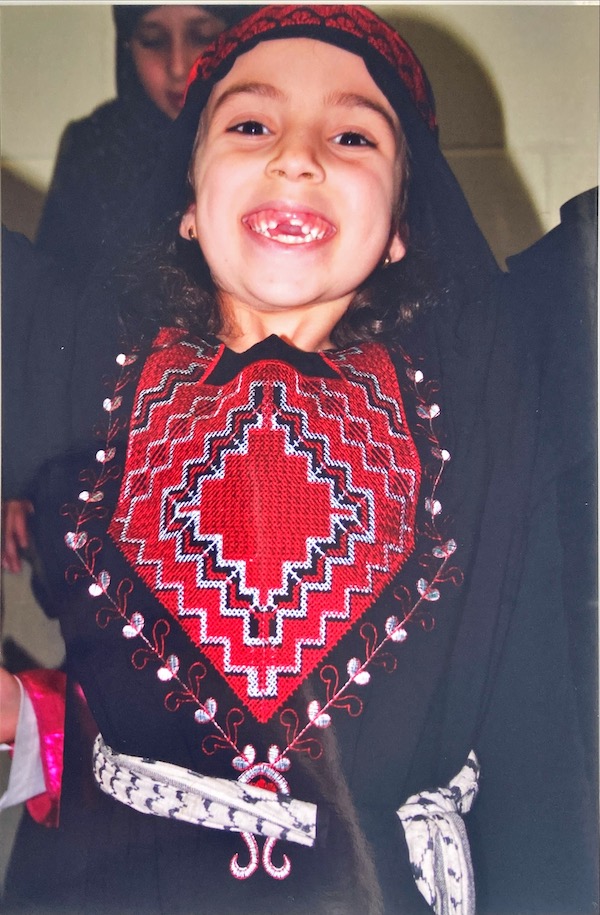

I discovered my love for tatreez the same way I discovered my love for most other things: at first sight. I love special occasions when I can pull out my thobes — the long, flowing traditional garments of our people — to twirl around in. I loved the first time my uncle told me that each pattern on my dress represented something. I love the colourful and intricate designs along the sleeves and down my back.

Tatreez is threaded throughout Palestinian history. A book called Traditional Palestinian Costume: Origins and Evolution by Hanan Munayyer traces it back more than 3,000 years, to the Canaanites who lived in the region at the time. The unique form of embroidery and patterns can be found as far back as 1200 BCE, where there have been depictions in ancient artwork of Canaanite women in dresses unique to their region covered in tatreez-like patterns.

Munayyer found that Palestinian fashion even had an impact on medieval Europe. Headpieces worn by European noblewomen had a strong resemblance to those worn by women in Bethlehem and embroidered Arabic calligraphy stitched in the same way as tatreez was found on European dresses.

Palestinian women used tatreez to represent different things. The quality of the materials they used for the thread and the dress itself could represent women’s socioeconomic status. The patterns stitched on the dress and the colours they used could represent a variety of things, including the region a woman is from to her marital status.

But when the Nakba happened, forcing Palestinian people from their land, women left with the clothes on their backs and their children in their arms. Pattern books and embroidering thread were left behind.

So how has this age-old tradition survived? Tatreez became a source of income for Palestinian women in refugee camps. They sold simple garments as a way to make some money for themselves and their families, and it helped them pass down the tradition.

However, it wasn’t as widely used. Women didn’t have the time or resources to stitch elaborate patterns, so it wasn’t very commonly practised in the years right after the Nakba, especially for Palestinians in the diaspora, like me.

In the 1960s, however, tatreez made a comeback — but in a different form. Instead of beautiful silks and threaded gold, women used plain cotton thread and cheap, functional fabrics. Patterns became more geometric as they acclimated to modern fashion and, as a result of the refugee camps that housed Palestinians from different regions, the patterns that defined different cities of Palestine were combined to create new ones. Tatreez became a symbol of Palestinian identity.

Palestinian women even used tatreez as a form of resistance. When the State of Israel banned the Palestinian flag after the Six Day War, Palestinian women stitched the flag and other symbols of Palestine on their clothes using the same colours of the Palestinian flag.

Today, tatreez is still a way of bringing Palestinians together. Worn on the traditional thobes or embroidered on purses, Palestinian women all over the world — in Palestine and the diaspora — continue to wear it, showing off their heritage.

Although tatreez is still around, not many Palestinian women know how to embroider it themselves. After the Nakba, many women didn’t have the time to stitch the same elaborate patterns, so they became not just simpler, but industrialized as well.

This was just a result of the lack of time and resources Palestinian women had after the Nakba. But they still found a way to pass on the tradition which, I think, is why tatreez is so special. It’s a symbol of the resilience of Palestinians and their dedication to keep their culture and traditions alive.

It was 21 years before I picked up a needle and thread and attempted to learn how to stitch. My cousin and I sat in her living room as her mother pulled out threads of every colour and showed us how to stitch the X’s that made up every pattern.

It’s a lot easier than I had thought it would be — and a lot more addictive. Now, every free moment I have is spent embroidering. It’s a way for me to feel more connected to my heritage, to bridge the ocean that lies between me and home.

When I proudly showed her my first flower, my aunt joked: “Now you’re officially Palestinian.”