Food security advocates warn many in the nation’s capital are likely without adequate nutrition as evidenced by the Ottawa Food Bank report of more than 400,000 individual visits in 2022 — the most in the organization’s 38-year history.

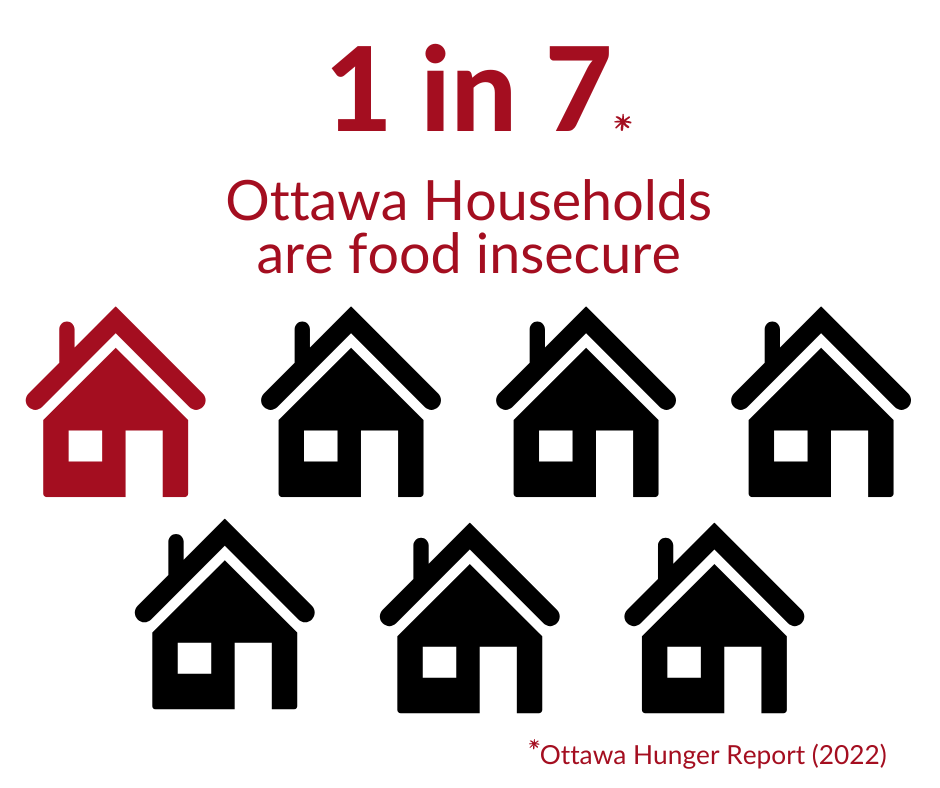

This figure is also a sharp 38 per cent increase from 2021. In 2022, one in seven Ottawa households reported food insecurity – in 2017, that number was one in 15.

“It is becoming increasingly difficult for individuals and families in Ottawa to afford healthy eating,” said Alex Noreau, interim communications manager at the Ottawa Food Bank.

The UN defines food insecurity as lacking “regular access to safe and nutritious food,” because of “unavailability of food and/or lack of resources.”

The Ottawa Food Bank collects and distributes food to more than 112 major food banks and programs in Ottawa. As the cost of living continues to rise, food bank programming is operating at levels never seen before.

Pre-pandemic, the organization spent about $1.9 million per year on food for distribution. This year, data shows it will spend more than $6 million. This is largely because of the rise in food costs, but also a sharp increase in the amount of food required to meet the needs of individuals accessing food programs in Ottawa.

“Food insecurity is a symptom of poverty,” said Noreau. “Food banks provide a wide range of support services to those facing food insecurity, but we know that more food is not a long-term solution.”

“People might think that people who are food insecure might lack food budgeting skills. Research shows that’s not true,” said Marketa Graham, a public health nutritionist at Ottawa Public Health. “People who are food insecure are very savvy with their money. They look for the best prices.”

The Nutritious Food Basket measures the minimum cost of healthy eating for individuals and families in Canada. It also determines the average cost to feed different genders and ages in Ottawa. Graham and colleague Emily Coja released last year’s annual report in October.

Although no data was published during 2020 or 2021 because of the pandemic, the last several reports have found a steady steep increase in food costs. A single adult, for example, would have to spend just more than $100 more on food per month in 2022 compared to 2016.

The most recent report found that a single adult on Ontario’s Disability Support Program, as well as a single adult and a family of four on Ontario Works, would have to spend more than 100 per cent of their monthly income on rent and a nutritious diet.

“Many are a paycheque away from needing to access a food bank for the first time," said Noreau. "There is nothing to be ashamed of. Anyone can find themselves in a position to need help, especially at a time like now.”

Graham and Noreau see this crisis as a primarily economic one, stemming from the soaring cost of living across Canada.

As part of a parliamentary investigation into food prices, the heads of several Canadian grocery chains testified in the House of Commons in March. Political leaders like Jagmeet Singh have alleged that profiteering from these companies is one of the factors driving this crisis in food costs. All three companies saw higher profits in the first half of 2022 compared to their average performance over the past five years. CEOs and presidents of Loblaws, Metro, and Empire defended their companies and denied these accusations.

“Income-based solutions have to be in place,” Graham explained. “We know that food cost has skyrocketed, and the reality is that people just don’t have enough money.”

Graham and Noreau also endorsed a re-evaluation of existing social assistance programs, which the Ottawa Public Health report found to be inadequate for several types of households.

“Increasing social assistance rates to keep pace with the cost of living and more affordable housing can positively impact the financial circumstances of individuals and families,” said Noreau.

Not every expert shares this focus on economic factors as solutions to food insecurity. Dalhousie University post-doctoral fellow Monika Korzun advocates for a three-pronged understanding of the issue, focusing on physical and social factors in addition to economic ones.

Physical and social barriers to food access, while less obvious, are just as serious and can exist independently of economic ones. Many communities across Canada, for example, exist in “food deserts” -- areas completely lacking in grocery stores.

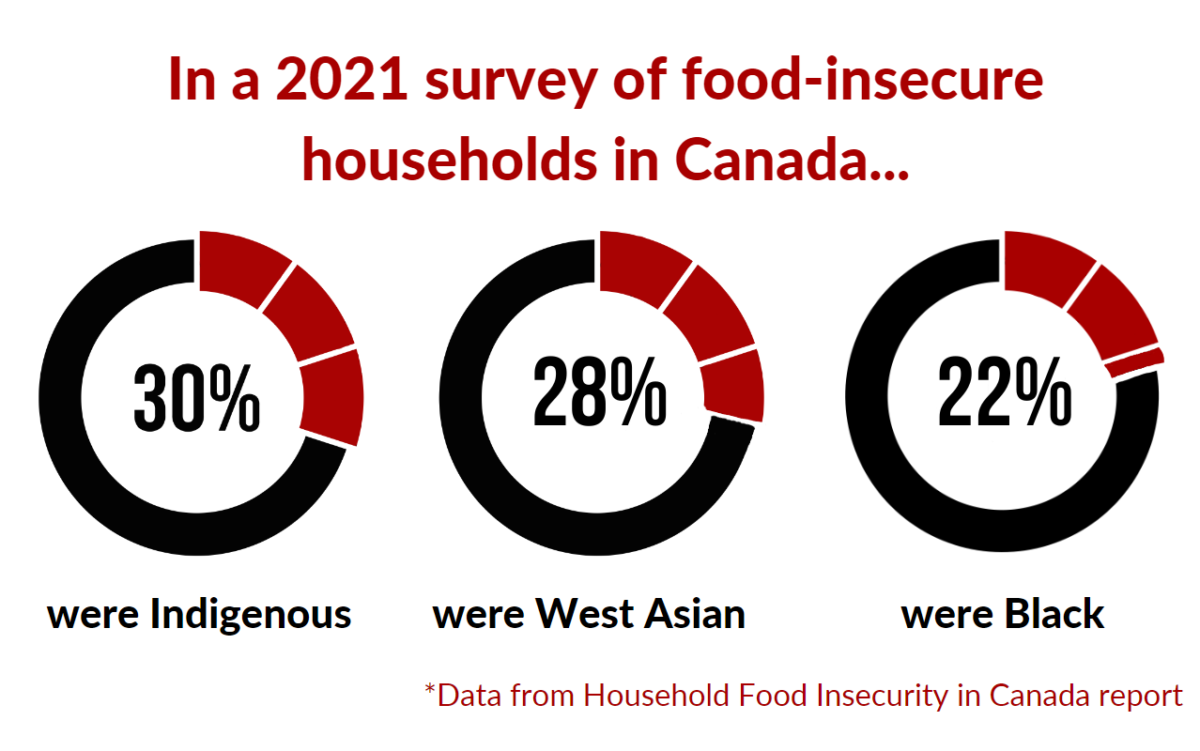

Korzun explained how an overly economic perspective of food insecurity can ignore important issues like accessing culture-appropriate food or growing one's own food. These concerns are particularly important for marginalized groups, who make up the majority of the food-insecure households in Canada.

Korzun said traditionally western solutions to food insecurity like food banks and income-based policies may not always be the best solution. The focus, she suggests, should instead consider larger systemic barriers to food access.

“Increasingly, we’re seeing that people are concerned about the bigger issues like racism and colonialism,” she said.

For Indigenous communities, the ability to hunt and fish for traditional diets is fundamental to the idea of food security. Policies that focus simply on providing money or food to these communities can ignore these important cultural factors.

For a recent report, Korzun described speaking to an anonymous Indigenous participant who explained their misgivings about the understood definition of food insecurity.

“Western views are like ‘OK you have to eat breakfast, lunch and dinner, and if you don’t eat those three meals a day, that means you’re food insecure,’” she said. “But from this participant’s perspective, Indigenous communities never ate that way. It doesn’t mean that they’re food insecure, that’s just not how they ate.”

Policies that would not be thought to affect food security can also affect marginalized groups. Municipal zoning by-laws can prevent people from growing their own food and the designation of federal or provincial national parks can lock Indigenous groups out of historic hunting grounds. This can make it difficult to access traditional diets, a common issue with the food bank system.

“A lot of communities rely on food banks, especially communities of colour, Indigenous communities rely on food banks,” Korzun explained. “But you won’t find deer meat in a food bank.”

While federal and provincial income-based policies are favoured by Graham and Noreau, Korzun suggests municipal solutions are the answer. A food charter similar to Ottawa's Climate Change Master Plan, in which the city commits resources and develops a long-term plan to tackle the issue, might be a good first step.

“A lot of the policies that are successful are coming from the bottom up," she said. "They’re not federal or provincial... It’s communities that know best what their members need.”

After facing pressures from advisory councils, the federal government currently has plans to roll out its first-ever national school food policy in an effort to increase access to nutritious meals for children in schools across the country. Examinations of food prices are currently ongoing by the Standing Committee on Agriculture and Agri-Food and Canada's Competition Bureau.

Still, Korzun says, without a focus on deeper systemic issues, the problem will linger.

“People will still be food insecure when food prices go down,” said Korzun. “The economic aspects matter ... but the food also has to be healthy, it should be nutritious, and it should be culturally appropriate. So food prices don’t address that.”