The Ottawa Coalition of Business Improvement Areas wants policy makers to extend repayment deadlines on loans many local small businesses received during COVID-19 to keep their doors open.

A recent survey for the OCOBIA shows many local businesses are worried about having to repay their Canada Emergency Business Account loans by a Dec. 31 to receive a one-third discount on payments.

OCOBIA represents 19 Business Improvement Areas including more than 6,400 businesses and 128,000 employees.

“The survey was conducted in response to a growing concern from businesses regarding their state and ability to repay CEBA … to receive the 33 per cent forgiveness from the federal government,” OCOBIA said.

The federal government offered CEBA loans to help businesses cover expenses during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eligible businesses were offered up to $60,000 and were promised a 33-per-cent loan forgiveness if their debts were paid by the end of 2023.

In Ontario alone, more than 360,000 businesses applied for CEBA loans, totalling some $19 billion in emergency assistance. Nationwide, the CEBA loan debt stands at more than $48 billion.

In the OCOBIA’s survey of 128 respondents, 67 per cent of concerned business owners were in retail or food service industries.

‘We were just breaking even. Without the loans to help cover the salaries, we would have been out of business.’

— John Kiffner, owner, Trio Bistro and Lounge, Westboro

The food service and hospitality industries were two of the hardest-hit sectors of the economy. Operating revenues for food services, for example, fell 24 per cent from 2019 to 2020, according to Statistics Canada.

Pure Kitchen, a vegan restaurant chain with five locations in Ottawa and about 175 employees, took out four CEBA loans of $60,000 each. Co-owner David Leith says Pure Kitchen’s revenue is 30 per cent lower than in 2019.

“Now it’s just managing more debt that you didn’t have before, with less sales,” said Leith.

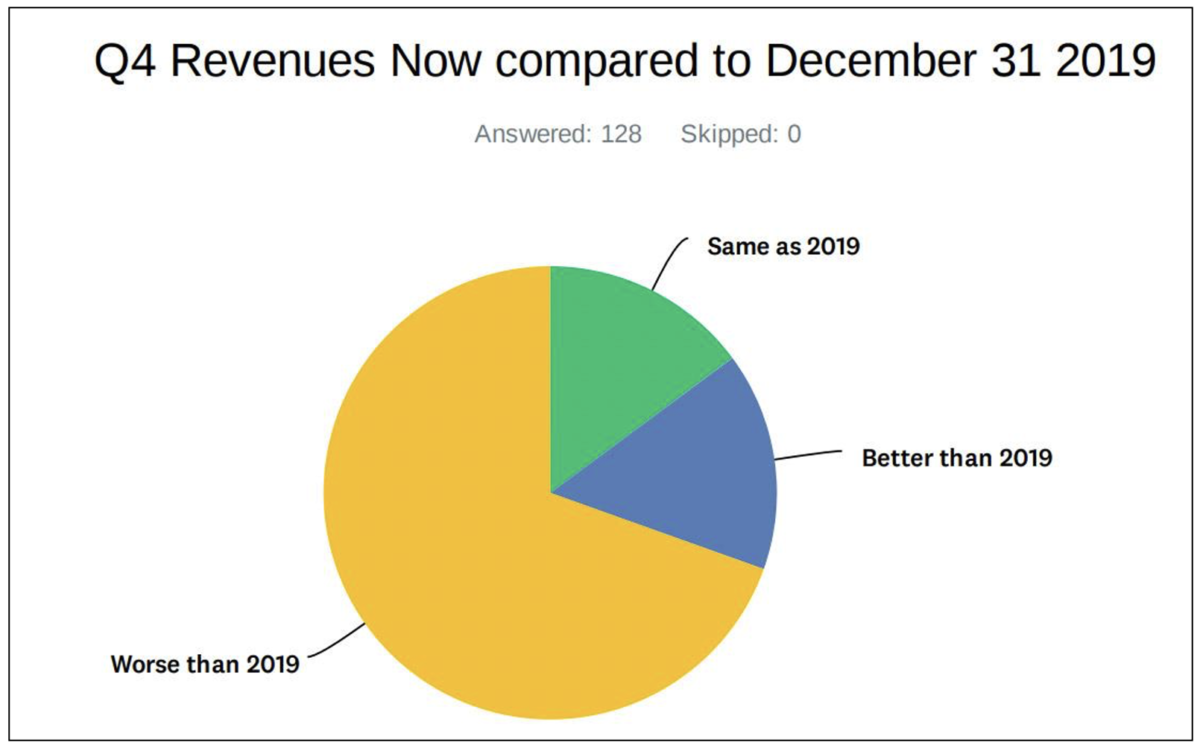

Many Ottawa restaurants face the same fate as Pure Kitchen. More than 69 per cent of the OCOBIA’s survey respondents said their post-lockdown 2022 revenue was below their pre-COVID 2019 revenue.

The issue is country-wide. Food-service industries across Canada saw a 21-per-cent decrease in sales from 2019 to 2021, according to Statistics Canada.

Along with the rising cost of food, liquor, labour and rent, Leith said changing consumer behaviour has resulted in his business’ declining revenue.

“We’re in a place of business where we’re relying on a lunch business that doesn’t exist anymore. No one’s in the office towers, no one’s in the government buildings, and if they are, it’s only one or two days a week. It’s not sustainable,” said Leith, who co-owns Pure Kitchen eateries on Elgin, Rideau and Preston streets.

Trio Bistro and Lounge in Westboro took out a full CEBA loan of $60,000 at the beginning of the pandemic. Owner John Kiffner said the loan was necessary to keep his business alive.

“We were just breaking even,” said Kiffner. “Without the loans to help cover the salaries, we would have been out of business.”

Trio, a late-night bar with seven employees, had a hard time transitioning to take-out only business during the pandemic, said Kiffner. While Pure Kitchen’s revenue was mostly based on food sales and that restaurant was able to commit to take-out and delivery, Trio struggled to stay afloat.

“We’re a cocktail bar,” said Kiffner. “We weren’t doing enough take-out.”

For bars like Trio specifically, the impact of COVID restrictions led to a year-over-year decrease in sales of more than 42 per cent, according to Statistics Canada.

Like Leith, Kiffner said the rising operating costs have affected his ability to pay off his loans.

“The worst part is food prices have gone up, the staff wage has gone up, now the booze tax,” said Kiffner. “It never ends.”

Kiffner was referring to the federal government’s planned 6.3-per-cent excise tax increase on beer, wine, and liquor that was to go into effect on April 1. In the end, the increase was held to two per cent for this year.

But the relatively modest alcohol tax hike will be followed by another Ontario minimum wage increase from $15.50 to $16.55 per hour on Oct. 1. The cost of food has also risen significantly, as Kiffner said, with an inflation rate clocked at 10.6 per cent in March, according to StatCan.

In its statement on the survey results, the OCOBIA warned: “Businesses are still in recovery and (are) still not ready to pay back pandemic-related debt — even by the end of 2023”.

The organization has released its survey results to policy makers and groups such as the Canadian Federation of Independent Business and Restaurants Canada, to warn them of the impact the impending due date will have on many small businesses.

‘I think there will be a lot of places that you’ll see in the next 6 months or so really biting the bullet.’

— David Leith, co-owner, Pure Kitchen chain of Ottawa vegetarian restaurants

Kiffner said the government hasn’t given businesses enough time to repay their loans. If Trio isn’t able to pay back its loan on time to qualify for the 33-per-cent forgiveness dividend, Kiffner said his business might not recover.

“If we can’t pay back the $40,000, we’re done,” said Kiffner.

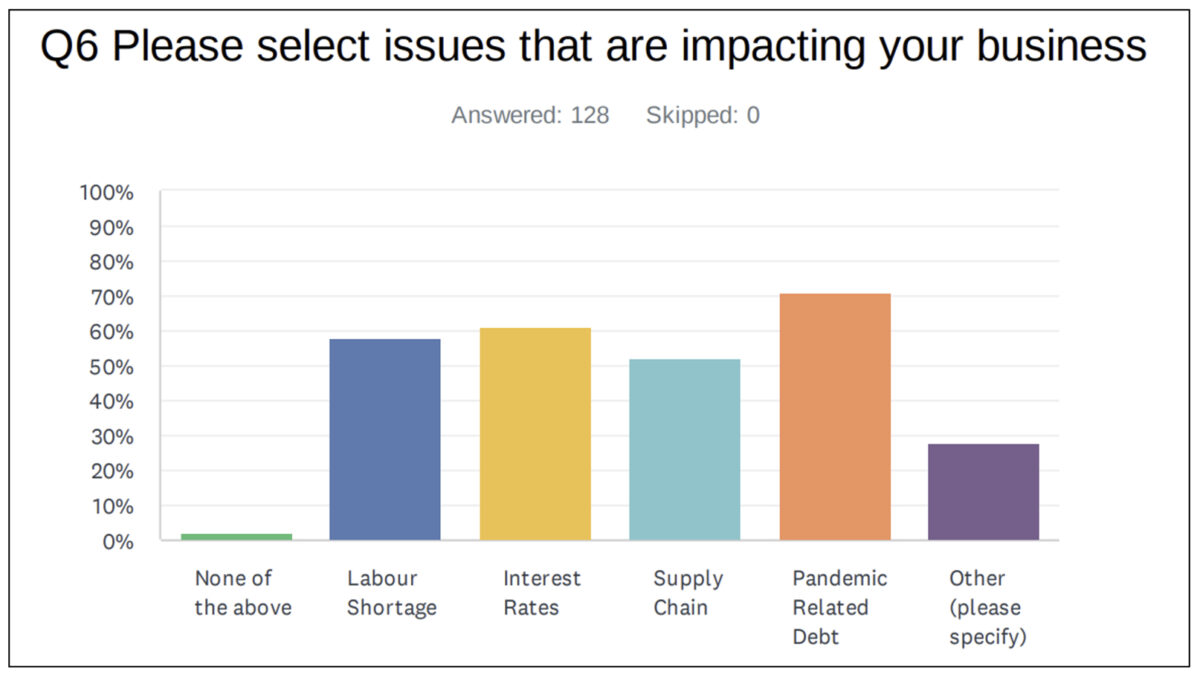

Other Ottawa businesses might be in the same boat. About 70 per cent of the OCOBIA survey respondents cited pandemic-related debts as one of their main financial concerns.

Leith said Pure Kitchen is on track to pay back their CEBA loans on time, but still has a large outstanding debt in HASCAP loans.

HASCAP (Highly Affected Sectors Credit Availability Program) loans were offered to businesses at the same time as the CEBA loans. While the CEBA loans came directly from the federal government’s pocketbook, HASCAP loans were government-backed bank loans. The HASCAP lending limit was $1 million, but the deadlines for repayment have already commenced for most borrowers.

Despite their debts, Leith and his business partners feel confident their restaurants will survive. However, Leith fears for the fates of others in the same industry.

“I think,” said Leith, “there will be a lot of places that you’ll see in the next 6 months or so really biting the bullet.”