When Bernadette Prevost started business administration at Algonquin College just before the pandemic, she hoped she could move out on her own within a few months of getting a job.

Instead, the 26-year-old still lives with her mother, despite having worked full-time in human resources for a year. The rising cost of housing and some leftover student debt means Prevost does not expect to be able to move until at least 2025.

“Don’t get me wrong, I love my mother; she’s a great roommate. But it’s hard.”

Prevost says her living situation has been “extremely limiting” compared to the life she saw for herself at 26, particularly when it comes to dating.

“It’s a huge obstacle because you can’t always afford to go out to a restaurant, but then again I can’t have potential partners come to my place because I live with my mother,” she said. “Some people don’t understand it’s really an affordability thing and not an immaturity thing.”

Prevost is not alone.

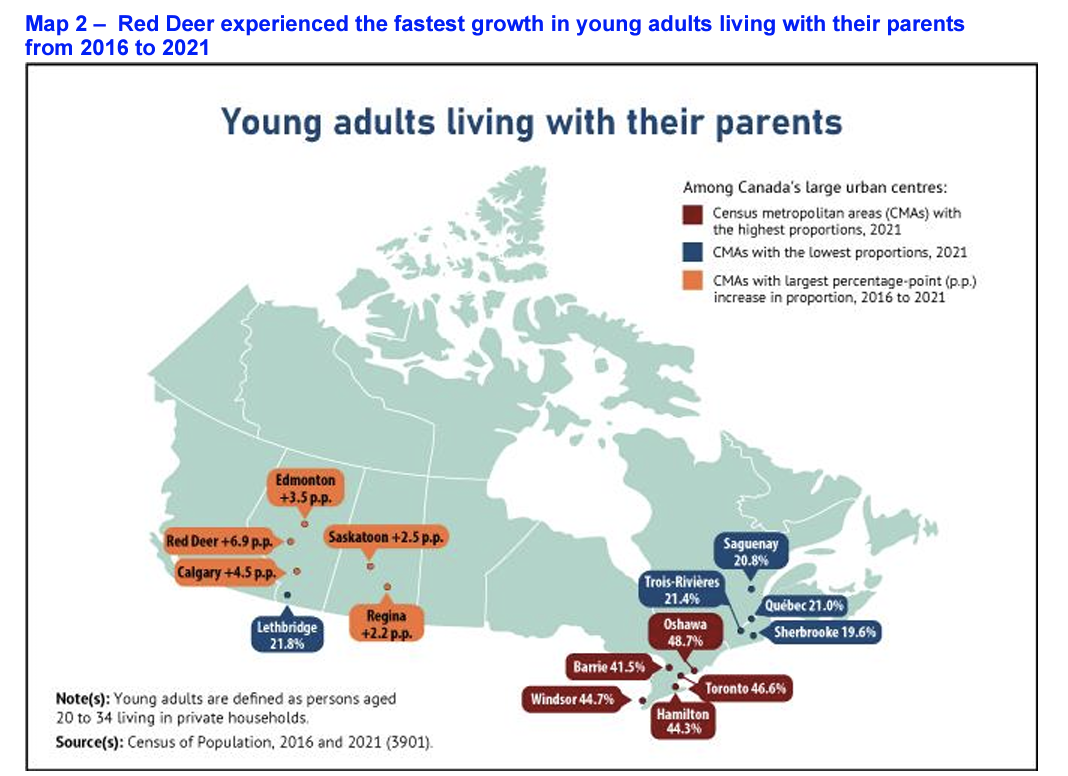

A 2021 report by Statistics Canada showed 35.1 per cent of young adults 20 to 34 lived with at least one parent, compared with 30.6 per cent in 2001. Results from the 2022 Canadian Social Survey said youth were 60 per cent more likely than older adults to report being “very concerned” about their ability to afford shelter.

Young Canadians are feeling the pinch. While some have found ways around it, many are reshaping their idea of adulthood.

What does housing cost?

For young adults, the cost of independent living is incompatible with their income. According to Rentseeker.ca, the average monthly cost for a one-bedroom apartment in Ottawa stands at $1,711.

“[That] would take one whole paycheque, just for rent,” Prevost said. “That doesn’t include utilities, parking fees, groceries, hydro, electric, phone, internet and whatever streaming services keep me sane.”

Other major cities have also seen steep increases in the cost of rent.

Originally from Ottawa, Jackson Clarke is a 28-year-old film student struggling to make ends meet in Calgary. He and his girlfriend of 15 years, who works full-time, rely on their parents to subsidize “about a third” of their housing expenses.

While Clarke says he feels “privileged” his parents can support him, he is “also aware it’s loaned money and working [him] away from homeownership rather than towards it.”

Clarke says the rent went up from $995 to $1,335 for their two-bedroom 700 square-foot apartment.

“[I'm] shocked and existentially concerned for my quality of life and the sacrifices I'll be having to make just to continue to have the same home, despite no value having been added,” says Clarke.

Despite the instability of renting, buying a home is not viable for most.

A 2023 report by Mortgage Pros shows 48 per cent of non-homeowners don’t see themselves ever being able to buy a home because of the rising cost of living, and only 17 per cent plan to buy a home in the next two years.

Sasha Patacairk, 21, is in her fourth year of a health psychology degree at Carleton University and working at a co-op full-time. She lives with her parents to save money.

Patacairk says she hopes to buy a home because “it would be a good investment.”

“I’m a little nervous about entering the housing market and seeing the state of it makes me never want to spend money until I need to buy a house.”

She says she is “mind blown” when older generations assume someone can afford a home from ‘working hard’. “That’s not how it works now.”

The business news website The Peak says it is three times less affordable to buy a house now, compared to 1980.

And a 2022 report by Generation Squeeze found it would now take prospective homeowners 17 years to save up for a 20 per cent down payment for a home, compared to five years in 1976.

Finally, the Bank of Canada's Housing Affordability Index shows this is the most challenging time since the early 1980s.

Clarke says statistics such as these are “depressing but shockingly accurate.” He says older generations are wrong to assume young people are responsible for their own financial struggle.

“It’s too much cognitive dissonance to just be explained away as some sort of moral failing.”

Despite obstacles, some young people are able to afford their own place. However, help from parents might still play a big role.

A recent study showed about 15 per cent of adults born in the 1990s in Ontario owned a home in 2021. The study found that of the people born in the '90s, those whose parents were homeowners were twice as likely to own a home in 2021 than those whose parents were non-homeowners.

There have been some programs to help first-time home buyers get their start.

The federal government provides a First-Time Home Buyer Incentive, offering first-time home buyers “five to 10 per cent of a home’s purchase price to put towards a down payment.” Some banks also offer a First Home Savings Account, allowing eligible buyers to save up to $40,000 tax-free for a future home.

Despite such programs, moving out remains disproportionately expensive for many young adults.

Data from the 2021 census showed that Canadians between 15 and 24 years old who do not live with their parents spend 23 per cent of their income on shelter costs on average, compared to 16 per cent across all age groups.

Prevost admits that if she really exercised her budget, she might be able to arrive in a different living situation, too. But to her, the sacrifices required to get there do not constitute affordability.

“In theory I could leave for independence, but the cost is so enormous that there’s no way any benefits could make up for it,” she said. “If I really knuckled down, I could, but that’s not the point of living. It's not sustainable.”

Changing the goalpost

Rising expenses are costing many young Canadians the lives they envisioned for themselves.

Clarke says he hopes to marry his girlfriend and raise a family, but he is putting that dream on hold to establish his career and pay off his debts.

According to Statistics Canada, 38 per cent of young adults aged 20-29 in 2022 said they did not think they could afford to have a child in the next three years. Moreover, 32 per cent believed they could not even access suitable shelter for a family in that period.

More than just family planning, affordability concerns are also pushing young Canadians further from independence and career goals.

Clarke says he is “taking a step back to go forwards.” After working in retail full-time for almost a decade, he recently went back to school in the hopes of landing a job that not only satisfied him but would pay better.

“I'll be 30 by the time I graduate, and in my head, I am a decade late with a significant amount of debt,” he said. “I've always felt homeownership should be a goal for us. It feels like a goal that is impossible to make progress on.”

Patacairk says rising costs are making her feel doubtful about moving out on her own.

“I don’t know how I'm ever going to be able to go for the house,” she said.

“I'll be 30 by the time I graduate, and in my head, I am a decade late with a significant amount of debt, I've always felt homeownership should be a goal for us. It feels like a goal that is impossible to make progress on.”

Jackson Clarke, 28 year old film student in Calgary

Even after staying home to cut expenses, Prevost says the cost of other necessities still leaves her without enough to fully enjoy this time in her life.

She says a stop for takeout on her way home after a long day at work might cost her the ability to afford some essentials later in the week. She describes “baring [her] teeth” for two months over the summer, eliminating all non-essential spending, just to afford to attend the Montreal Pride Festival in August.

Prevost says she hopes growing discussions about affordability will mitigate assumptions about young adults who are still financially dependent on their families.

“No one wants to admit they’re struggling financially because there’s a lot of shame from it,” she said. “If we rewire ourselves to be less judgmental, a lot more people would be more comfortable talking about finances … which would hopefully instill some policy change.”

“You can’t change what you aren’t aware of.”