Her heart racing, Wati Rahmat hurries down a side street, heading to the closest bus stop from her office in Montreal. A car is slowly trailing her. She knows what’s coming. Sure enough, as she turns around, a man rolls down the side window of the car and yells, “You terrorist! Go back to your home!”

That is just one of the frightening episodes Rahmat, an Asian Muslim who wears a hijab, faced during the nine years she spent in Montreal. It finally got so bad that she moved to Edmonton in 2014, hoping things would be different there.

They were not.

Time after time, she said, strangers would approach her on the street, demanding, “Muslim, why do you wear hijab? Why do not you become a Canadian?”

“The undercurrent of Islamophobia is always there in Canadian society,” said Rahmat, adding that Muslim women are easy pickings for racists because “Muslim women are visible.”

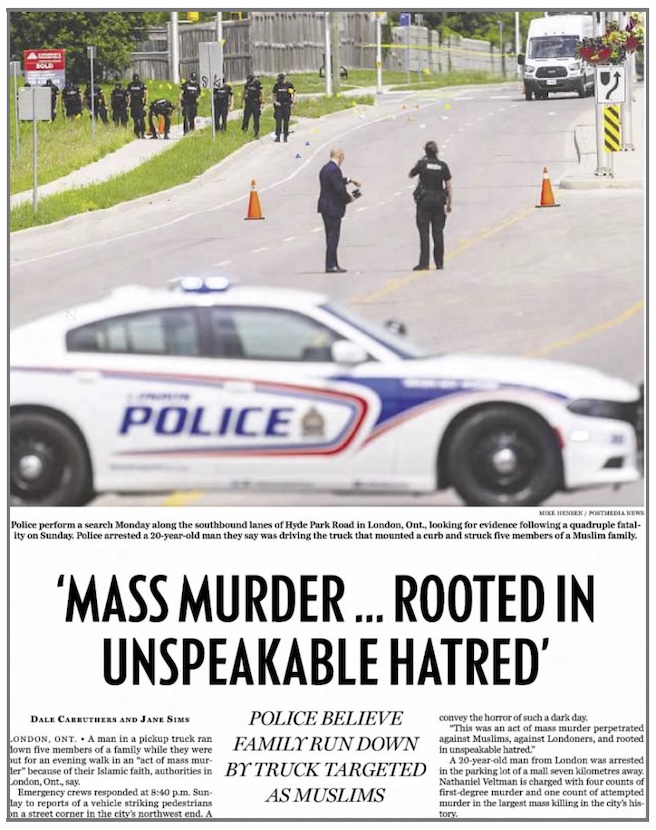

Hate crimes against Muslims have soared in recent years, from the slaying of a Muslim man outside a Toronto mosque in 2020, to a June 2021 truck attack on a Muslim family in London, Ont., that killed four people the next year, to hate-related incidents targeting two Markham mosques in April of this year.

In 2021, the National Council of Canadian Muslims reported that more Muslims have been killed in targeted hate attacks in Canada than in any other G-7 country in the previous five years.

The incidence of police-reported hate crimes against Muslims rose by a staggering 71 per cent from 84 to 144 between 2020 and 2021, according to Statistics Canada. The actual number is incidents is certainly much higher, as nearly 80 per cent of hate incidents are not reported to the police, according to The Canadian Anti-Hate Network.

And Muslim women have borne the brunt of these incidents. In the last two years, the majority of victims of Islamophobia were women, said Rahmat, referring to incidents covered by the media as well as information from community organizations.

‘Muslim women are targeted because attackers think they are weak and will never fight back. They are attacked and harassed because of the prevalent stereotypes of being oppressed in their communities. That assumption makes their attack permissible.’

— Chelby Daigle, editor-in-chief and coordinator, The Muslim Link

As recently as April 12, a Muslim woman driving home from a mosque in Kitchener reported that a masked man rolled up next to her car, lowered the window and pointed a gun at her and her mother; police are investigating.

In Edmonton, at least nine attacks on Muslim women were reported to police over a six-month period in 2020-21, according to the Edmonton Journal. These included an incident in which a man allegedly smashed the side window of a parked car at a local mall to assault a mother and daughter inside the vehicle, and another in which an attacker reportedly knocked one woman out and held a knife to the throat of another in nearby St. Albert.

Muslim women are singled out not only because wearing the hijab or niqab makes their religious affiliation instantly identifiable, but also because of Islamophobic stereotypes, observers say.

“Muslim women are targeted because attackers think they are weak and will never fight back.

They are attacked and harassed because of the prevalent stereotypes of being oppressed in their communities. That assumption makes their attack permissible,” said Chelby Daigle, editor-in-chief and coordinator of The Muslim Link, an online forum for exploring the diversity of Muslims in Canada.

The impact of the pandemic has helped to drive up hate crimes against Muslims in general,

and Muslim women in particular, according to Daigle. As thousands of people lost their jobs and faced isolation at home during pandemic lockdowns, many turned increasingly to social media, where misinformation and disinformation were rampant. White supremacists and right-wing extremists were quick to exploit this trend, accelerating a global resurgence of the far right that was already underway when the pandemic struck.

These ideologies are deeply intertwined with misogyny, said Daigle, adding that the rise of misogyny intersects with the rise in attacks on Muslim women.

“The economic situation during COVID-19 and mental health problems (arising from the pandemic) generated a lot of issues, one of which was getting radicalized in social media. Many people got radicalized … because of the intense messages they received from online platforms,” she said.

COVID-19 conspiracy theories only added to this trend. For example, one such theory claimed that Muslims were defying lockdowns by secretly gathering in mosques to pray. In June and August 2020, one Toronto mosque was vandalized six times.

Meanwhile, a demographic shift in Canada has added fuel to the fire of white supremacists. The share of the Muslim population in Canada has more than doubled in the last 20 years, up from two per cent in 2001 to almost five per cent in 2021, according to Statistics Canada.

This change has helped fuel support among some for the so-called “great replacement theory,” which claims that some people in Canada are conspiring to try to replace native-born Canadians with immigrants who support their political projects. Social media have helped amplify this theory, according to Daigle.

A 2022 survey by Abacus Data indicated that 44 per cent of Canadians believe in at least one conspiracy theory, and 33 per cent believe in replacement theory. Systemic racism and the failure of governments and other key institutions, such as police forces, to address it are also responsible for Islamophobic attacks, critics say.

‘People need to understand Muslims come from different places, different cultures, different histories, and they are not only one thing.’

— Amatur Rahman Salam-Alada, student, Carleton University

Police often respond to reports of hate crimes with indifference or denial, Rahmat said, adding that police often fail to investigate. This leads many racialized people to distrust the system, she said.

“In one incident, a police officer says to a Muslim woman, ‘Racism is not a crime! You know!’” says Rahmat. “In another incident, one of our sisters says, ‘Why should I report if nothing is going to happen?’”

Rahmat and other members of the Muslim community in Edmonton decided to take action after the wave of vicious attacks in 2021. They founded Sisters Dialogue, an organization that brought together a diverse group of Muslim women.

In the summer of 2022, the group launched The Edmonton SafeWalk program in collaboration with the Edmonton Federation of Community Leagues. It was a pilot program that paired

Muslim and racialized women and girls with volunteers while they are out doing their daily tasks, or just getting some fresh air. The program has now ended.

“Women have the right to feel safe and comfortable everywhere and anytime. There is still neglect and underestimation of what women experience and suffer,” said Rahmat.

Godlove Ngwafusi, chairman of the Anti-Black Racism Committee of The African Canadian Association of Ottawa, said systemic racism is ingrained in the police hate-crime reporting system, and “it does not give credence to Black people … or marginalized people.” Ngwafusi said he has noticed a rise in frustration and distrust in the communities and organizations he works with.

Despite the rise in hate crimes, people are reluctant to report them because “there are no

consequences,” he said, adding that unless a police officer’s job “is on the line, (and they are) facing consequences immediately, nothing is going to change. And here is the problem. No one gets fired because they are racist or negligent.”

Naila Miled, the anti-racism advisor at the University of British Columbia’s Faculty of Medicine, emphasizes that the issue of Islamophobia in general, and gendered Islamophobia in particular, has not even been effectively addressed in Canada yet.

Miled has been tracking the representation of Muslims in Canadian media for years. She said the role of media in perpetuating stereotypical images of Muslims, especially those of Muslim women, has normalized a distorted image of Muslim communities.

“We only see Muslims either depicted as victims or depicted as terrorists. We do not see Muslims as normal and real people who are having their stories in the media like other communities,” Miled said.

Miled also said some laws and institutions contribute to the normalization of systemic Islamophobia, including gendered Islamophobia.

Advocates point to Quebec’s Bill 21 as a sign that Islamophobia and systemic racism persist not only within police forces, but within governments as well. Muslim women are at the centre of the controversy over Quebec’s Bill 21, which forbids civil servants in positions of authority, such as police officers and teachers, from wearing religious symbols such as the hijab, turban and kippa. A 2022 study by the Association for Canadian Studies found that Muslim women were the group most deeply affected by the law.

Islamophobia is significantly higher in Quebec than elsewhere in Canada, research suggests: a new study by the Angus Reid Institute found 56 per cent of Quebec residents have negative views of Islam, compared with 36 per cent outside Quebec.

In January 2017, six people were killed and five seriously wounded in a shooting at a Quebec City mosque. The gunman, 27-year-old Alexandre Bissonette, had immersed himself in right-wing, anti-immigrant, Islamophobic online material before carrying out the attack. He was later convicted for the mass murder and sentenced to life in prison.

The debate over Bill 21 heated up again in January when Prime Minister Justin Trudeau appointed former journalist Amira Elghawaby as the Canadian government’s Special Representative on Combatting Islamophobia. Pointing to an opinion column she had co-authored in 2019 criticizing Bill 21 that mentioned the prevalence of anti-Muslim sentiment in Quebec, Bloc Québécois Leader Yves-François Blanchet demanded Elghawaby’s resignation. He stuck to this position despite her Feb. 1 apology for her past remarks, in which she said, “I am extremely sorry for the way that my words have carried, how I have hurt the people of Quebec.”

Elghawaby’s role is to support and advise the federal government in fighting Islamophobia, systemic racism, and racial discrimination by ensuring that religious intolerance and prejudice against Muslim communities do not penetrate into legislation and institutions.

Her appointment comes as a part of the government’s response to the 61 recommendations tabled by the National Council of Canadian Muslims at a national summit on Islamophobia held in July 2021, partly prompted by the terrorist attack in London.

An accountability report released by the NCCM one year after the summit found that some progress had been made. In all, 27 of the 61 summit recommendations have been addressed by different levels of government, including a federal commitment to join a legal challenge of Bill 21 if it reaches the Supreme Court.

Meanwhile, advocates are calling not only for improvements in police response to hate crimes, but also for better support for victims.

“There are a lot of systemic issues, including the lack of support programs, and there is no consideration of the social and cultural layers when it comes to Muslim women,” said Rahmat, referring to the diverse customs and religious representations within Islam. “We do not ask to be special, but to be understood,” she emphasized.

‘We do not see in the media enough narratives about Muslims’ success stories and achievements. We need narratives that bring real Muslim stories, we need to go beyond stereotypes.’

— Naila Miled, anti-racism advisor, University of British Columbia Faculty of Medicine

Better public education is also key in combatting the prejudices that underlie Islamophobia, activists say.

Amatur Rahman Salam-Alada, a Black Muslim student at Carleton University, said many non-Muslims rely on stereotypes. For example, she said, many people have expressed confusion about “how a Black woman can be a Muslim,” and asked her: “Where are you really from?”

“People need to understand Muslims come from different places, different cultures, different histories, and they are not only one thing,” said Salam-Alada.

Other times, Salam-Alada added, people have remarked: “Oh! You speak English very well; where are you originally from? They assumed that because of who you are, you can’t speak English properly.”

Meanwhile, some educators are tackling the problem of Islamophobia in the classroom. Earlier this year, the Peel District School Board became the first in Canada to adopt a strategy aimed at combating Islamophobia, creating more inclusive classrooms and affirming Muslim identities — especially by acknowledging Muslims’ contributions to science, art, and history. Muslim students comprise about 25 per cent of the PDSB’s student population.

The step was praised by many Muslim communities.

Miled agrees dismantling stereotypes is critical: “The more we educate people, the more people realize Muslims are normal people, instead of only depicting them as either victim of domestic violence or victims of Islamophobia.”

Media coverage is a big part of the problem, Miled added: “We do not see in the media enough narratives about Muslims’ success stories and achievements. We need narratives that bring real Muslim stories, we need to go beyond stereotypes.

“Muslims are human,” she said, “and part of the social fabric that contributes to Canada.”