Gregory Brown didn’t find out his newborn son, Jack, had CHARGE syndrome until he was 11 months old. Because Jack’s condition left him immunocompromised, Brown said for his family, the public health precautions that began during the pandemic were things they were already doing.

“For Jack’s sake, it was just another day for two years.”

In Jack’s early childhood, spending time in the hospital wasn’t just common, but vital, Brown explained, noting his son’s need for emergency surgery.

Now, hospital emergency rooms are seeing double or triple the usual rate of young children, as recently reported by the Toronto Star, with increased likelihood of surgery cancellations as a result of the ER spike. As of Nov. 14, Ontario’s chief medical officer issued a renewed appeal for the province’s citizens to wear masks in indoor settings to slow the spread of respiratory viruses like the flu and COVID-19.

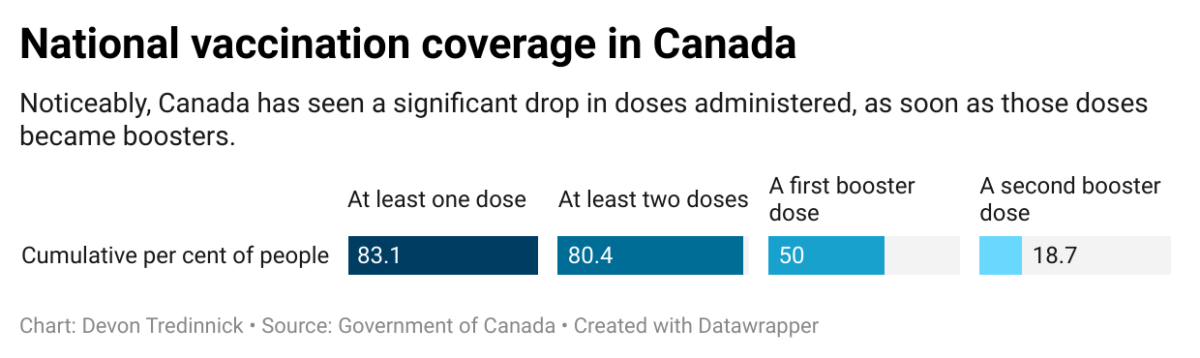

Yet fewer than half of all Canadian children between ages five and 11 have two or more doses of a COVID vaccine. It raises the obvious question of why so many parents have hesitated to fully vaccinate their children.

And when people start trusting vaccine-hesitancy propaganda — whether it’s because of a history of discrimination, or susceptibility to online misinformation and self-serving political leaders — the need to dispel it comes at a crucial time.

Heather Camrass is a registered nurse and the executive director at the Community Nursing Registry of Ottawa.

Her job hasn’t been easy.

Camrass explained how she has had to deal with vaccine hesitancy coming from both the clients and nurses she works with.

“There’s about 10 per cent of our group who really struggled to get it,” said Camrass.

‘A lot of that misinformation, or disinformation, looks like reputable science. It’s going to take a lot of effort to overcome that.’

— Michael Halpin, sociologist, Dalhousie University

She also spoke about her fear that vaccine hesitancy could be on the rise because of people’s lack of experience with certain diseases and the vaccines made to combat them. She said she believes there will come a time when older diseases come back and people who are vaccine hesitant will have to start embracing vaccination again.

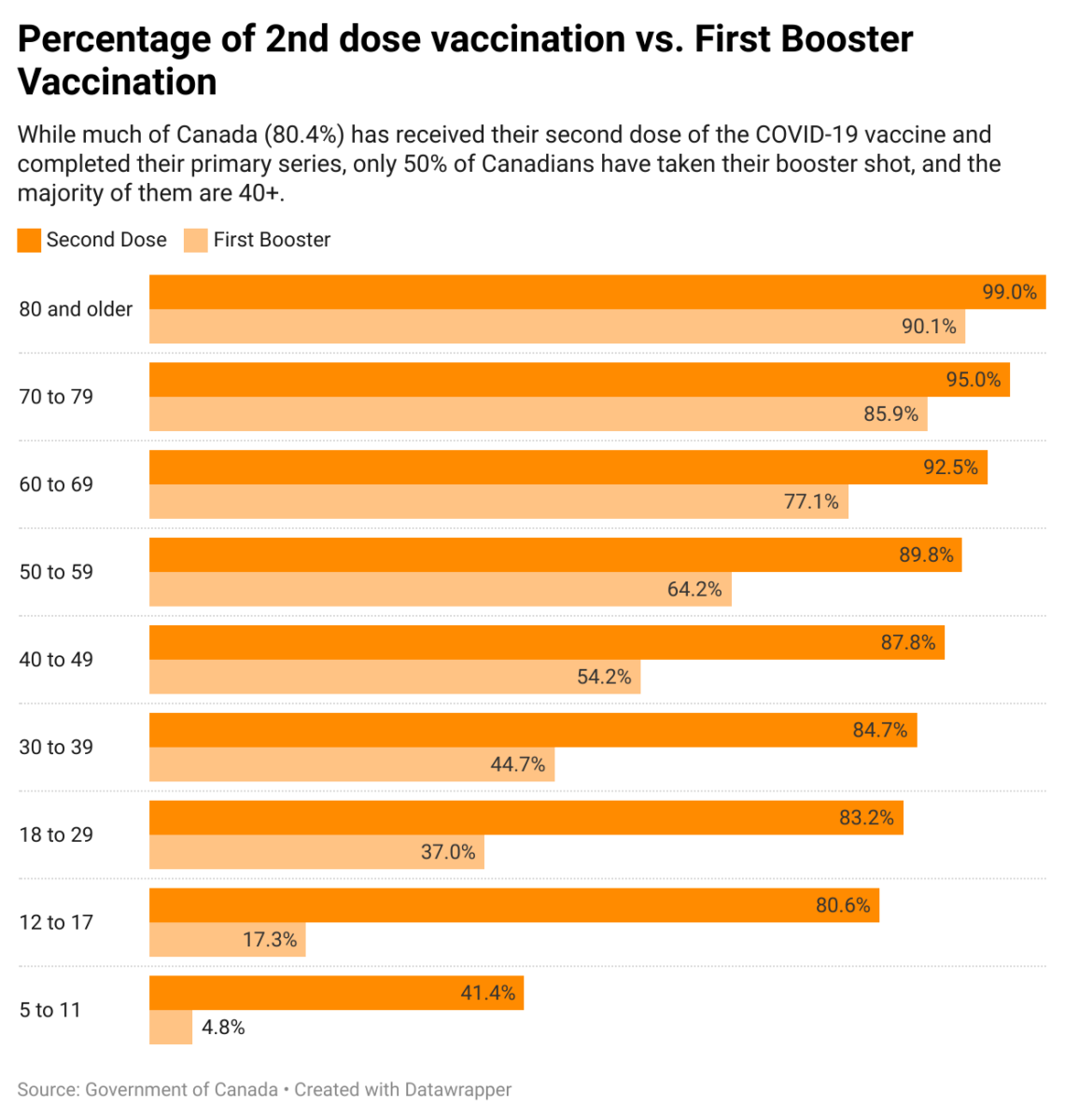

Camrass’ idea that experience with infectious disease leads to vaccination tracks with the current COVID-19 vaccination statistics, which show vaccination rates increase as Canadians get older. 95 per cent of all Canadians aged 70-80 have received two doses of a COVID vaccine, compared with 83 per cent of Canadians aged 18-29, according to federal government statistics.

Camrass also isn’t the only one concerned about vaccine hesitancy with news indicating the phenomenon is on an upward trend. A recent study adds evidence that Canadians could be more likely to be vaccine hesitant due to their social surroundings.

Michael Halpin, a sociologist at Dalhousie University, said there are social factors that breed vaccine hesitancy and public health authorities need to address the issue.

Halpin acknowledged there’s a deep history behind some people’s skepticism towards public health, particularly for groups with bad relationships with the medical system, including Black Canadians, Indigenous Peoples and women.

“Part of the issue, in terms of vaccine uptake or hesitancy, is that prior relationship, or disrupted trust that’s happened there,” he said.

Basically, until the COVID pandemic, there had been little effort made to repair those damaged relationships, Halpin added. He noted the lack of reconciliation around First Nations nutrition experiments, when the actions of some Canadian medical doctors led to the deaths of many people in First Nations communities.

“It can’t be resolved just when it becomes convenient for medicine or public health,” said Halpin.

Originally from Alberta, Halpin reflected on the influence of that province’s premier, Danielle Smith, who sparked outrage in October when she said the unvaccinated population is the most discriminated-against group she’s witnessed in her lifetime.

Halpin added that misleading statements like Smith’s damage not only vaccine uptake, but also general social cohesion. But Smith isn’t the only one hyping up vaccine hesitancy; Halpin points to the endless streams of vaccine misinformation available online.

“A lot of that misinformation, or disinformation, looks like reputable science. It’s going to take a lot of effort to overcome that,” he said.

In October, Ontario opened its Omicron-targeted, COVID-19 vaccine appointments for anyone aged 12 and over, as indicators showed the virus was on the rise.

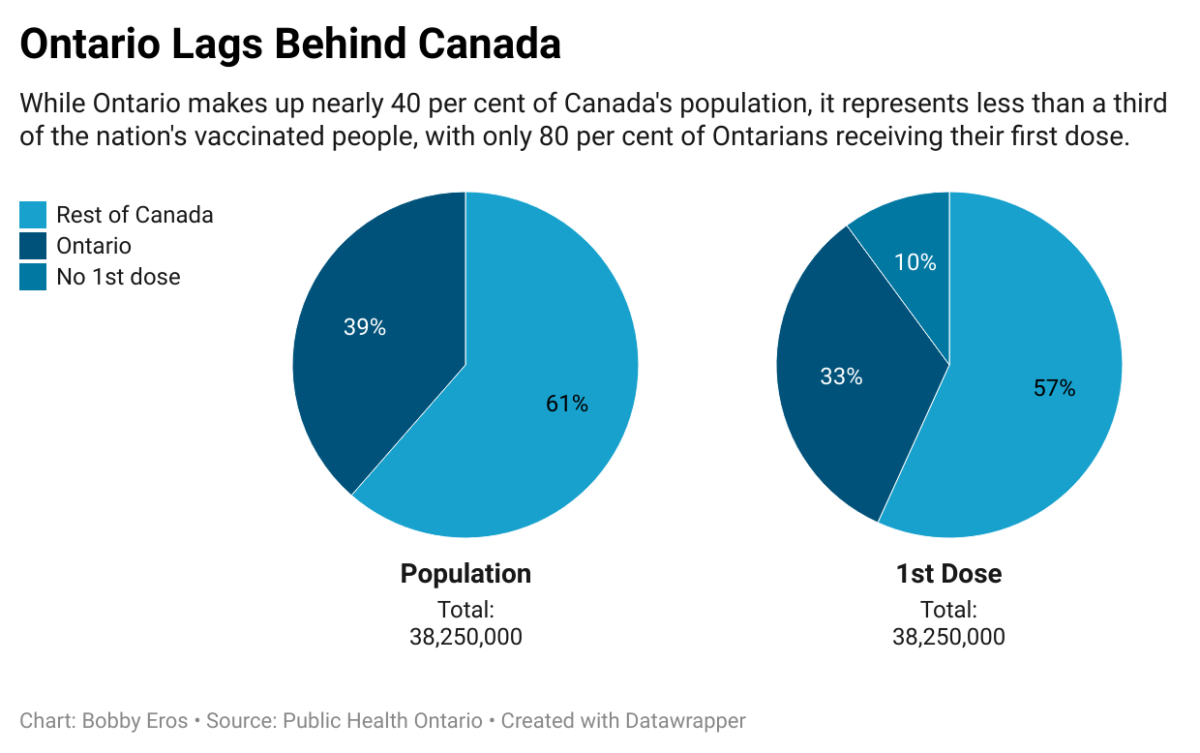

While Ontario has administered 35 million doses, the total vaccination rate of the province is below the national average, sitting at 80.7 per cent of residents having received at least one dose, according to Public Health Ontario.

That’s 10 per cent shy of the province’s target goal, according to Dr. Paul Roumeliotis,

medical officer of health for the Eastern Ontario Health Unit.

Michael Christensen is an assistant law professor at Carleton University, researching vaccine misinformation shared on social media. He emphasized that many people are looking for alternative information when it comes to vaccines.

“The biggest part of this,” Christensen said, “is people who are looking for information that fits the need to question these public health mandates.”

‘The biggest part of this is people who are looking for information that fits the need to question these public health mandates.’

— Michael Christensen, assistant law professor, Carleton University

The impulse to question authority has been a key part of the problem, Christensen explained. And with pharmaceutical giant Pfizer planning to sell its COVID vaccines, pushing vaccination can seem like a cash-grab rather than a vital public health initiative.

“I think we’re still learning how to operate in a world where there’s so much information around us, people can curate their own streams of information,” said Christensen.

Both Christensen and Halpin mentioned a need for more accessible information about vaccines as a solution for misinformation and vaccine hesitancy.

“My hope, if there’s hope, is that public health communicators and science communicators have learned from this,” Christensen said.

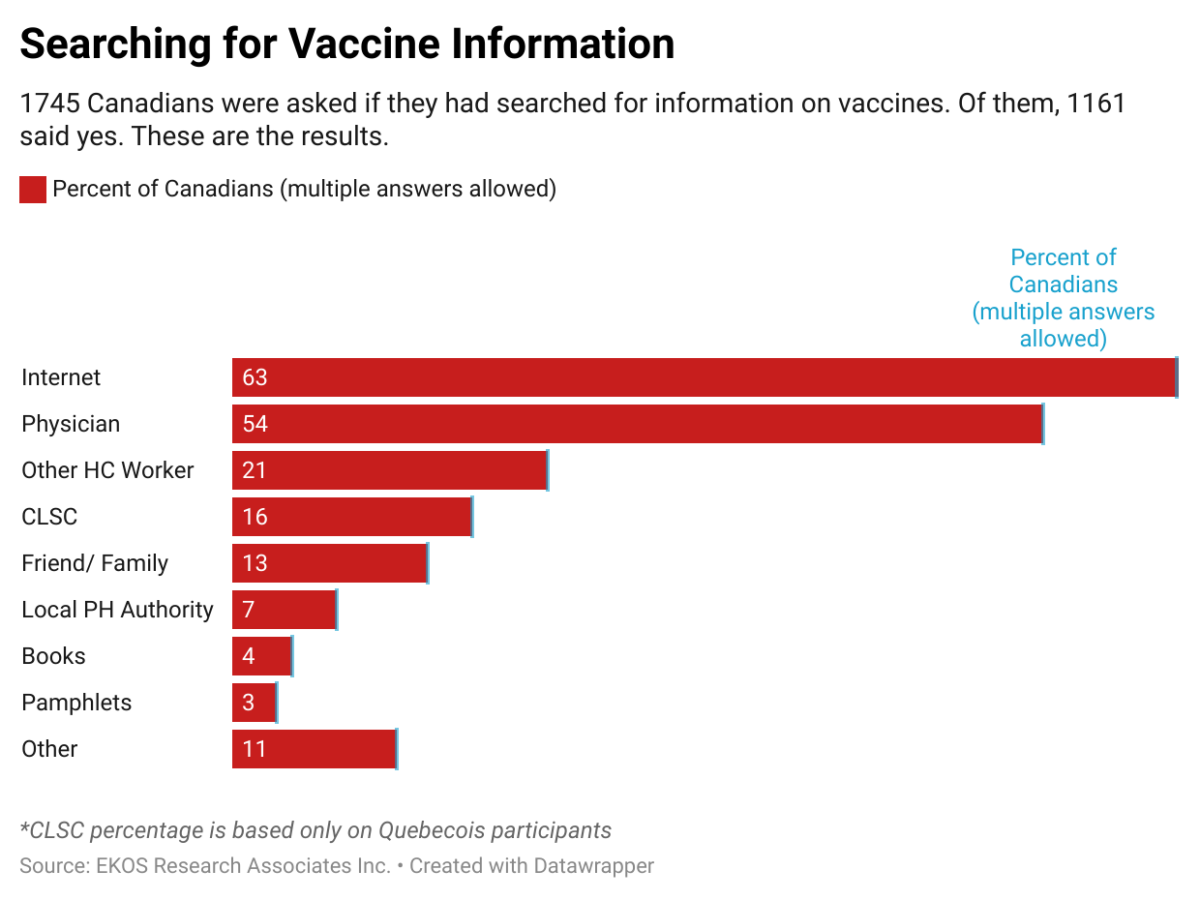

Vinita Dubey, Toronto’s associate medical officer of health, has also conveyed the impact the internet can have on vaccine hesitancy, as close to two-thirds of Canadian parents said they checked online for information on immunization — a digital sphere where it’s not always easy to tell information and misinformation apart.

“Fortunately, more than half of Canadian parents continue to receive information about vaccination from their physicians,” Dubey wrote in a 2019 research paper. And those who talk with family doctors are less likely to have vaccination concerns.

In that same paper, Dubey also mentioned many parents who are vaccine hesitant will still immunize their children for one disease, but not another, often under-immunizing them rather than neglecting immunization altogether.

But with the number of anti-vaccination websites providing false information, it can be hard to combat hesitancy — especially with nearly half of Canada neglecting to speak with a doctor about their fears, according to the Government of Canada.

It’s not all bad news on the home front, though. CTV recently reported that Ottawa has one of the highest third-dose COVID-19 vaccination rates in Ontario. With only one million residents and 2.5 million doses distributed in the city, Dubey also notes that half of Ottawa has vaccinated themselves against the most recent Omicron variant.

Dr. Vera Etches, Ottawa’s chief medical officer, warned in a Sept. 13 public announcement that the winter months will see another spike in COVID-19 cases. Christmas 2021 saw Ottawa’s largest weekly spike in cases of the entire year, with more than 7,000 new cases reported across the city.

With many Canadians still not seeking a booster shot, there’s no certainty about what’s in store during the holiday season and throughout the winter of 2022-23. Canada’s Health Minister Jean-Yves Duclos, though, has advocated for more children to get their COVID-19 shots to counter surging hospital admissions.

As for Brown, he noted his son has received a number of vaccines in school, and is soon planning on getting his first booster shot. And although Jack is non-verbal, Brown noted his emotions are quite evident through his facial expressions.

“Jack communicates a lot through his eyes. When he winks at me, he’s telling me he loves me, or thanks me.”

One of Jack’s more recent winks, said Brown, includes one given to his bus driver when he got his first ride to school.