David McGee loves the silly stories that have emerged on Lost Ottawa in recent years.

For those who may not know Lost Ottawa is a Facebook research community devoted to images of Ottawa and the Outaouais up to the year 2000.

McGee has captured the conversations that emerged on the site in his most recent book, Lost Ottawa 3.

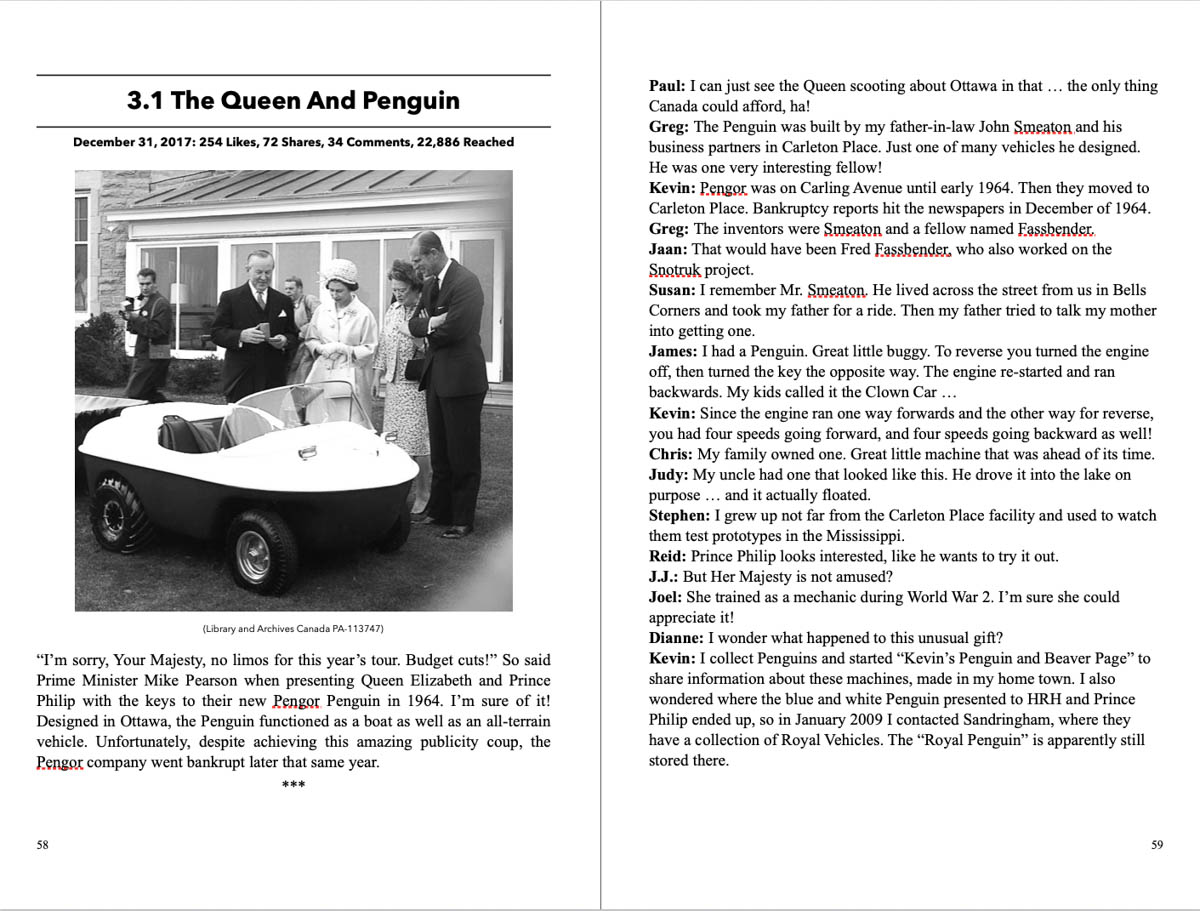

Filled with bicycles, stories from the suburbs, memories of bomb shelters, Le Hibou coffee house and a photo of the Queen, it’s the result of his online interactions with people through the Lost Ottawa site. The site, started in 2013, has nearly 55 000 followers and counting.

Lost Ottawa 3, now available on Amazon, is one of many local history books to hit the stands in recent times. There’s Phil Jenkin’s new book, As I walked About, and his updated An Acre of Time about the history of LeBreton Flats. There’s Ottawa Rewind 2 by Andrew King, Capital Builders by John McQuarrie and a host of others. The Historical Society of Ottawa also releases local history pamphlets by a variety of authors.

McGee started the project to see if people would want to interact with local history using Facebook. As a historian, he wondered, “Can we get people to engage in history using these newer tools? … And if so, what would be the history that interested them?”

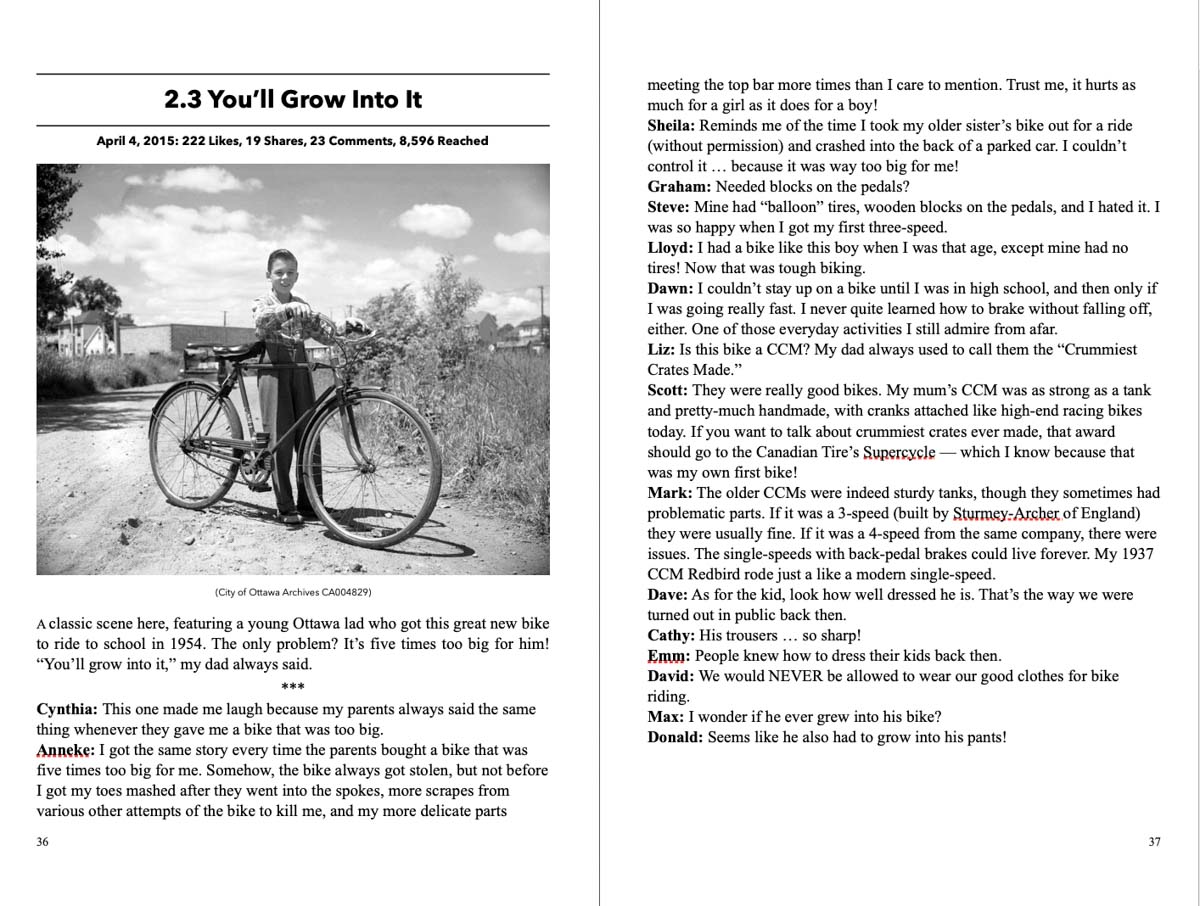

“I want communities to start talking about their experiences with bicycles, and how they used to ride around on them and how it gave them freedom to go wherever they wanted,” McGee said. “It was a really, really important part of their childhood to have a bicycle.”

Only in modern times has it become possible to share history online. Digital archives are a recent development that has changed the way historians look at sharing information.

“[W]hat we’re doing is new, but it really wasn’t possible before,” McGee said.

Through sharing digital images of the way Ottawa used to look, people can have conversations about how the city has grown and changed. The best of these make it into McGee’s books. Interestingly, while McGee has made videos for Lost Ottawa, they don’t garner the same popularity and conversation as the photos.

McGee said he hoped for a “tiny improvement of their experience of the city by knowing a little bit more about what used to be on that corner; and that would show people in a way that history still affects them.”

Connections like this are often made on Lost Ottawa. Robert Graham has followed Lost Ottawa’s Facebook page for about a year. “It’s interesting how places around Ottawa I’m familiar with looked in the past and how the city has evolved over the years,” Graham said.

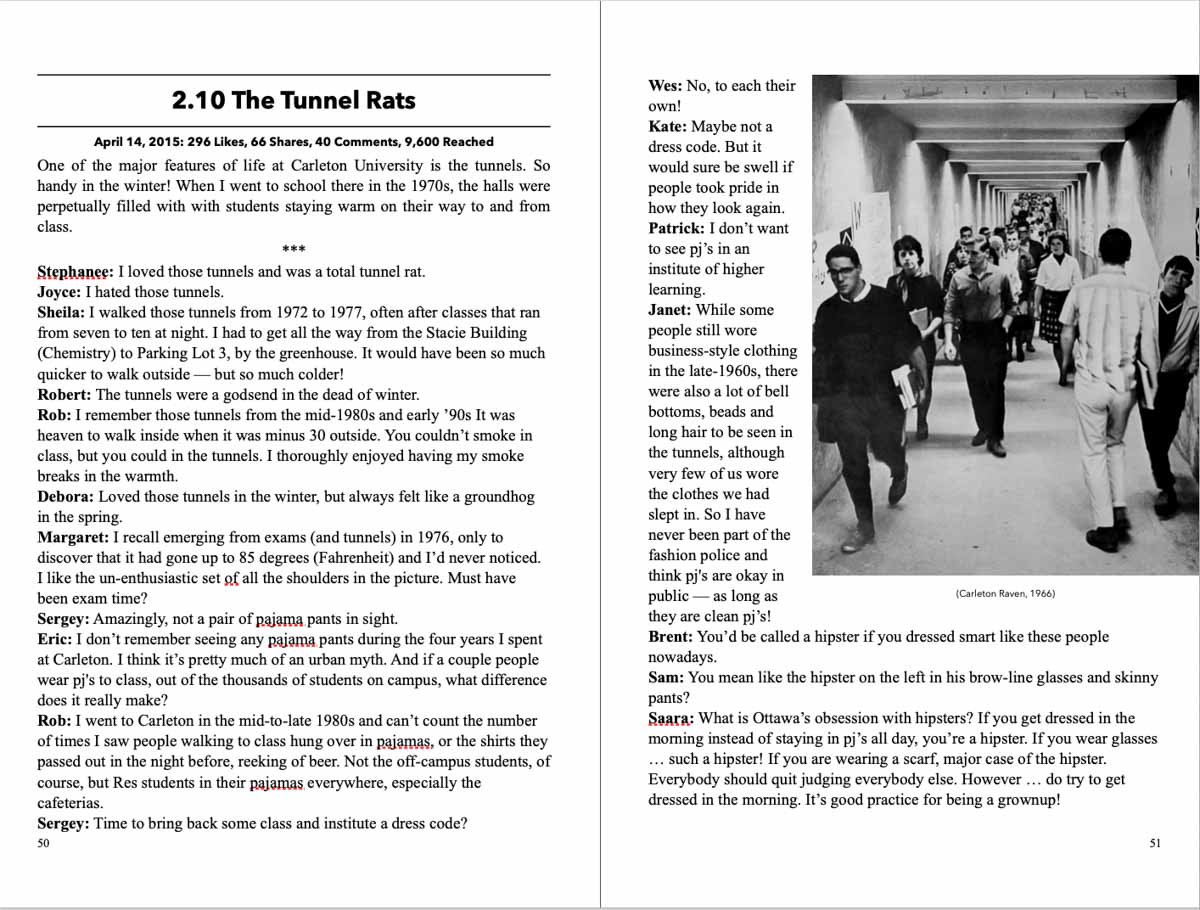

For the conversations featured in the Lost Ottawa books, the narrative is usually based in shared memories and experiences.

Randy Boswell, a local history buff and journalism professor at Carleton University, said, “There’s a bit of nostalgia, I think, that is being satisfied.”

He compared the stories Lost Ottawa tells to those that are shared when a family sits down over the holidays to swap stories. “[Y]ou remember the house that you grew up in or certain past times when you shared it with your siblings,” Boswell said. He believes people instinctively want to share memories and reflect on the past.

Some experiences, however, tend to be shared more than others.

“I’ve noticed that the community doesn’t really like to talk about divisions. They don’t like to engage in things, discussions about what might separate us,” McGee said.

With Lost Ottawa’s focus on built surroundings and memories intertwined with them, it is easy to overlook the importance of where things were built and who inhabited the land prior to the founding of Ottawa. Boswell says that local history tends to start in the early 1800s, despite the rich history the land had before it was settled by white people. He said this is often talked about as the beginning of history for an area.

“Well, that’s a pretty glaring oversight in terms of the history of the places in Canada,” he said.