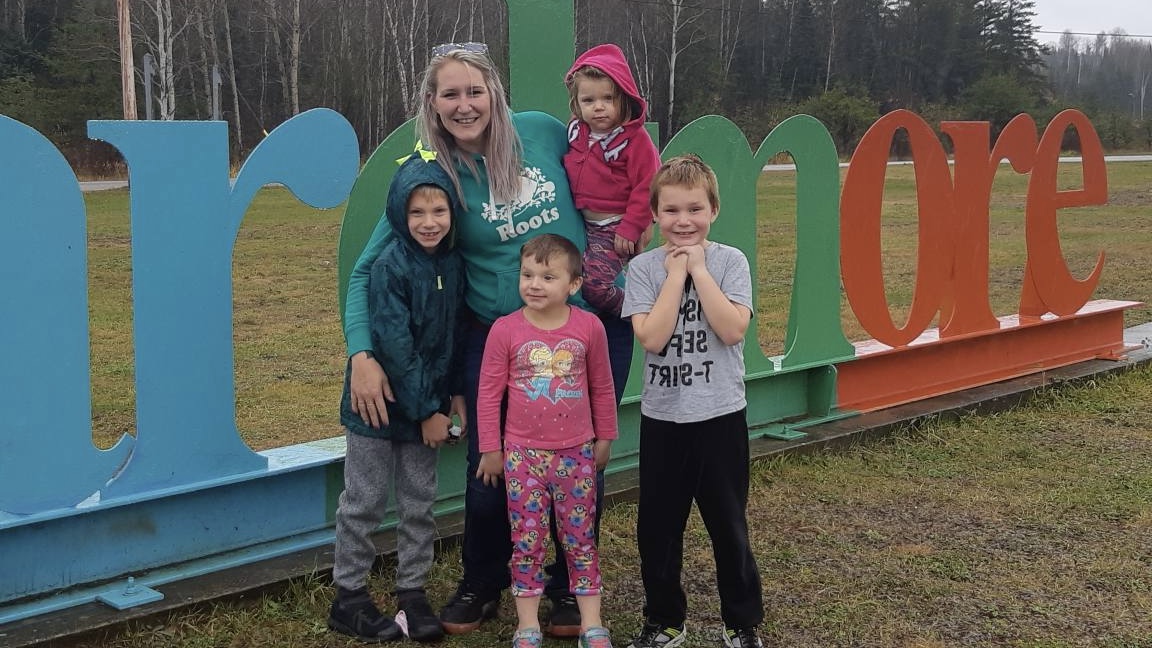

Megan Davey, a 30-year-old Ottawa resident and mother of four, never fit in with her family. As a pansexual woman — which she describes as basing her attraction on spiritual connection rather than gender identity — she said she, “never really fit in with their morals.”

“I always felt like the black sheep, and I still do in a lot of ways,” she said.

At age 16, when her parents still could not come to terms with her sexuality, she left home, unable to cope with her family’s casting aside of her identity and other forms of emotional abuse.

“I was dating a girl at the time and they would always say to me, ‘It’s just a phase,’ and it would drive me crazy,” said Davey.

With no place to go, she found herself homeless. She spent the next year and a half bouncing between shelters, couch surfing and even living on the streets for three months. For members of the LGBTQ2+ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and two-spirited) community, Davey’s experience is not uncommon.

An analysis published by Statistics Canada released in December 2020 found that 77 per cent of survey participants that reported having lived in a shelter, on the street, or in an abandoned building at some point identified as LGBTQ2+. Many experts have deemed this number to be disproportionate, given the total amount of queer-identifying individuals in Canada was only 13 per cent as of 2017, according to the Jasmine Roy Foundation.

Many of these same experts fear the COVID-19 pandemic could exacerbate these numbers.

Unaccepting households

John Ecker, the director of research and evaluation at the Canadian Observatory on Homelessness, has studied the LGBTQ2+ community specifically. He said homelessness within the LGBTQ2+ community — particularly among youth — is often linked to a lack of acceptance by the households of queer individuals.

“It could be family rejection based on one’s sexual or gender identity, having parents that kick you out of the house because they don’t accept your identity,” he said.

Ecker emphasized the prevalence of homelessness amongst LGBTQ2+ youth specifically. According to a survey featured in Where Am I Going To Go?, a 2017 book produced by the observatory, 51 per cent of the LGBTQ2+ youth participants said they had experienced homelessness as a result of being unable to get along with their parents. Only 36 per cent of heterosexual respondents said the same.

This phenomenon, Ecker said, could worsen as a result of COVID-19, particularly as young people are forced to spend more time at home with family members who might not accept them and with LGBTQ2+ youth having less access to support outside of the house, as well.

Potential discrimination from employers and landlords, continued Ecker, could also result in continued homelessness for members of the LGBTQ2+ community, leading to increased unemployment and/or lower wages — an issue already prevalent within the queer community.

Money matters

Alongside its evaluation of LGBTQ2+ homelessness, the Statistics Canada analysis also indicated LGBTQ2+ individuals are disproportionately more likely to earn less than $20,000, and are less likely to earn more than $60,000.

Elena Prokopenko, a research analyst at Statistics Canada and one of the lead authors of the study, said these findings aligned with previous research on the topic, and that LGBTQ2+ individuals could find themselves even less likely to make it to higher-income brackets during the pandemic.

“The majority of the LGBTQ2+ respondents also identified as being between the ages of 15 and 24,” she said. “Many of the sectors these people work in — food service, retail, etc. — have been seriously affected by the pandemic, meaning it could be much harder for them to earn more, or even earn at all.”

This is a significant reason, added Prokopenko, why more LGBTQ2+ Canadians may be forced into homelessness during the pandemic.

Though Davey said her time as a homeless LGBTQ2+ youth was “awful” — leaving her with financial and emotional strain that was difficult to overcome — she said she would never change anything about her past. She said her experience has made her more compassionate, helped her discover her passion for social work, and made her a better mother.

“It’s really shaped me to be a better person and to be able to educate my kids on issues related to homelessness — and hope we make a difference.”