The One World Bazaar isn’t your average shop stop. It’s a 6,000-square-foot Ottawa barn quite literally filled to the brim with handmade goods from all over the world — the majority of which are locally sourced by the bazaar’s globetrotting, Ottawa-based owners from more than 2,000 artisans in 20 developing nations.

Shelves of hand-painted dishes and elaborate wooden art pieces line the outside of the building under a roof overhang. The interior is a colourful collection of irresistible trinkets and exotic eye-catchers.

One World Bazaar celebrated its 40th anniversary this year. The celebration was marked with a giveaway contest in which the lucky winner got the chance to custom-create a piece of furniture or a painting by meeting the artisan over video chat and seeing the production process firsthand.

“It’s a way to give back to our community,” said owner Anneka Bakker.

The bazaar is open for seven weeks in the fall each year inside an old barn in the village of Manotick, at the southern edge of urban Ottawa. Bakker’s uncle, Paul Gervan, started the business with his wife Evelyn near Kingston in 1981. He was a world traveller and had the idea of bringing home handcrafted goods to sell in Canada, something he hadn’t seen done here before.

Gervan ran the successful business for 22 years until retirement, when he passed it on to his sister Peggy Bakker and her husband Dick. They relocated the bazaar to Manotick, transforming Dick’s parent’s unused barn into an international marketplace.

The couple’s daughter, Anneka,bought the business last spring and 2021 was her first year running the show, although she’s been involved since the ripe old age of five.

“This year has been really good,” Bakker said before the bazaar shut down Nov. 14. “There’s a totally different energy with customers around comfortability being out of the house. People are generally more comfortable which leads them to come in droves. The crowds have been very strong.”

The business has experienced high demand through its online store, which was launched in September 2020 to accommodate customers during the pandemic, said Bakker.

Although the bazaar is only open for a handful of weekends each year, running the business is a year-round job that requires lots of planning. One World has up to 12 employees working throughout the year, then staffing goes up to 50 staff during the in-person sales season from September to November.

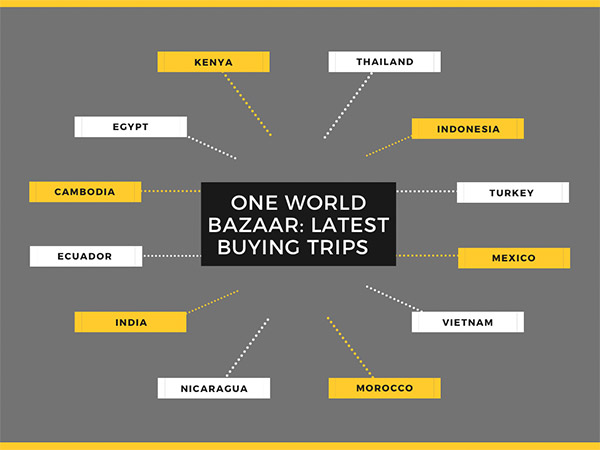

Each year, the owners go on “buying trips” to various countries, purchasing goods from local artisans.

Ensuring economic stability for their producers is one of the core values of the business, said Bakker, adding that providing living wages for artisans allows them to support their families.

One World follows a fair-trade model and is committed to fairness in equitable pricing, she said.

“There’s some artisans we’ve been working with for almost 38 years. We’ve seen their businesses grow and get passed down to the next generation and that happens alongside our business evolving, as well,” said Bakker.

“There’s some artisans we’ve been working with for almost 38 years. We’ve seen their businesses grow and get passed down to the next generation and that happens alongside our business evolving, as well.”

— Anneka Bakker, owner, One World Bazaar

She said her family knows 80 per cent of the producers personally and the business is seeking fair-trade certification this year.

The pandemic slowed buying trips in 2020 and halted them altogether in 2021, so everything had to be bought remotely. Supporting craftspeople in developing countries who lost 90 per cent of their business due to the pandemic’s impact on global tourism was especially important this year, said Bakker.

“We put in our order for our coffee wood beaded chandelier and the artisan told me we were the first order they’d received all year — three and a half months into 2021. His wife was pregnant and due to that order, he said he now had enough money to allow her to have the baby in hospital and care for the wife,” said Bakker. “What gets us up in the morning is knowing that we directly impact the lives of others in ways that we don’t always know.”

The One World Bazaar features products from Vietnam, Turkey, Indonesia, Thailand, Ecuador, Mexico, Nepal, Bolivia, Guatemala, Kenya, India, Bangladesh, Cambodia, Namibia, South Africa, Morocco, Egypt, Peru, Costa Rica and Cuba. Jewelry, clothing, garden decorations, furniture, art, musical instruments, holiday decorations, lighting, and home decor can all be found inside.

“In Indonesia alone, we’re working with 100 artisan businesses,” said Bakker. The Bakker family further supplements their inventory by buying from wholesalers in Canada who source and sell products from developing nations.

Clients this year could be seen leaving the old barn with terracotta tableware from Mexico, hand carved wooden puppets from Bali, teak chairs crafted in Java, vibrant cotton cardigans from Thailand, and mini Buddha statues from Indonesia.

Miranda Rice has been a loyal customer since the early 2000s and decided she loved the place so much she’d get a job there this year. She worked in the furniture area.

“I have all kinds of little treasures all around my house from this place. Seeing this family supporting artisans around the world is just great. They’re exposing Ottawa and the greater area to these wonderful treasures that people couldn’t get on their own,” said Rice. “People come in and they’re so excited and happy to be here. It’s just a really nice environment to work in.”

“Everything is selling, there’s almost nothing in storage,” said Bakker. “People are certainly investing in their homes and spaces; that’s a trend we saw last year and it continued into this year. Furniture basically has been walking out the door, and paintings too.”

Bakker said she added a furniture room extension to the building this year in response to popular demand.

The bazaar showcased its artisans by including little info cards beside their displayed products. Beside the driftwood carvings, a little card identified the artisans as the Liong Su family from Ubud, Indonesia. Husband and wife Ketut and Wayan, along with their son Made, each have a role in their family business. Made collects the driftwood from rivers near his town after heavy rainfalls, then his parents design and carve the material.