Ontario’s registered nurses’ union is warning of a worsening shortage of care-givers, as survey data shows a significant increase in young nurses’ desire to exit the profession.

“We need to save this profession so we can save people,” said Dr. Doris Grinspun, CEO of the Registered Nurses Association of Ontario (RNAO).

Nurses under 35 are more likely to want to leave, according to a survey of Ontario’s registered nurses (RNs), by the RNAO, published during March, 2021. Young nurses “have the chance to turn around and basically save ourselves from entering this field,” said 29-year-old Alexandra Garcia, a registered practical nurse (RPN) working in home care in North York, Ont.

The survey shows the rate of Ontario RNs who said they intend to leave the profession multiplied by four during 2021, said Grinspun.

According to data from the College of Nurses of Ontario, the professional regulator for nursing in the province, about 2.7 per cent of RNs aged 30-34 did not renew, or otherwise lost their membership during 2020. In contrast, the survey data from the RNAO reported 13.3 per cent of nurses aged 31-35 reported they are “very likely,” to leave the profession after the COVID-19 pandemic.

In the companion analysis to the survey data, the RNAO reported that 15.6 per cent of all respondents could leave within a year. If all respondents who said they intended to leave "after the pandemic" or "within one year" actually did so, there would be a "net loss of 10.8 per cent above the background rate."

The Ontario Hospital Association (OHA) said it is working to “implement appropriate measures to rebuild Ontario’s health workforce,” in an emailed statement.

For her part, Alexandra Garcia said she was frustrated with the lack of support young nurses receive from the government, hospitals and their older colleagues.

Garcia, who has also worked as a nurse in a North York hospital, said she wasn’t surprised by the survey results.

When nursing students complete the hands-on portion of their training known as ‘clinical,’ Garcia said that older nurses will hand students the more difficult parts of the job.

“We are there to support and help but we're not ultimately there to carry everything for you. It is ultimately a learning experience,” said Garcia.

“Nurses eat their young,” she called the phenomenon. Garcia said older nurses throw early career nurses “into the lion's den.”

According to a 2020 inquiry into the history of nurse bullying in Canada for the journal of Quality Advancements in Nursing Education, Garcia's experience reflects the pre-established culture. Rather than attributing the prevalence of bullying to individual failings, the authors said the normalization of bullying is caused by many factors, "such as misuse of power, structural constraints, corporatization of health care, hierarchical structures and divisiveness."

Despite organizations, institutions and individual acts to rid nursing of bullying, this history of bullying is reflected in the lived experience of nurses like Garcia.

Abusive patients are another issue that Garcia said isn’t being dealt with.

"Take the abuse and take it because you know like, that's what we are. We're nurses. They treat us like it's okay to be a punching bag," said Garcia.

Nurses are expected to continue treating patients who inflict verbal and physical abuse, she said.

Concerns had been raised about abuse towards nurses before the COVID-19 pandemic began. According to a 2019 report from the House of Common's standing committee on health, a brief from the Canadian Federation of Nurses Unions reported 61 per cent of Canadian nurses experienced harassment, abuse or assault in the year prior.

"Workplace violence is a pervasive problem in health care settings across Canada," according to the report. "Health care workers have a fourfold higher rate of workplace violence than any other profession. And yet, most of the violence experienced by health care workers goes unreported due to a culture of acceptance."

“When we bring it up to our employers, the only action I've noticed is there's a poster," said Garcia. "There's posters on the unit saying that they won't tolerate abuse.”

Training was a resource in short supply during the pandemic, said Garcia. At her last position, she said she was supposed to receive a couple months of training, which was reduced to four shifts.

“So, because of the abrupt training, because we keep getting new nurses, we cannot retain enough nurses. A lot more errors are definitely prone to happen, especially in long-term care,” said Garcia.

Grinspun said the anticipated losses are more than the system can take.

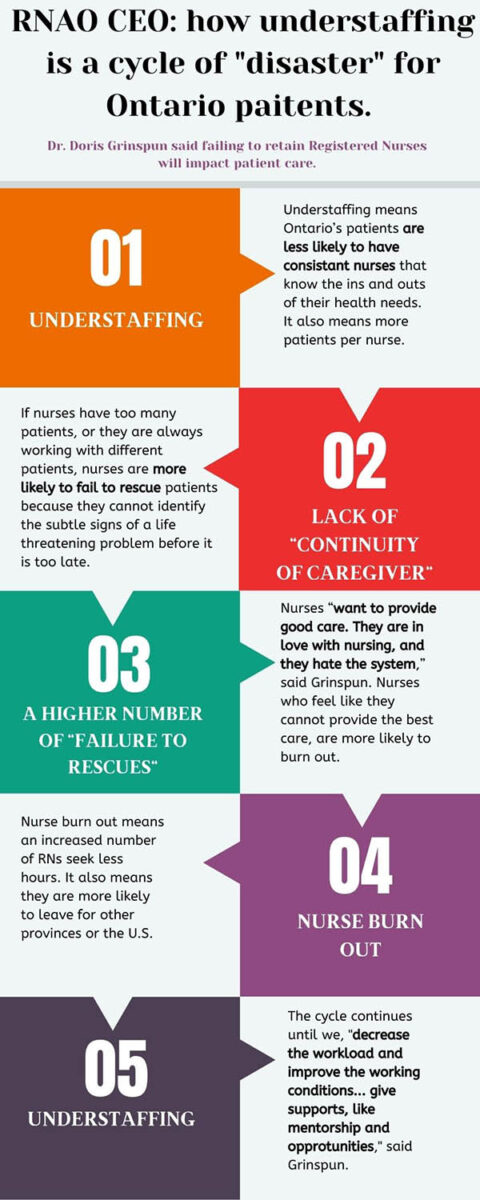

She warns that understaffing disrupts the continuity of caregivers which increases the chances of missing subtle changes in a patient’s condition and more frequent “failure to rescues.”

Nurses want to provide good care but they have too many different patients to do so. The result is burnout, said Grinspun.

Continuity is especially important for long-term care because the facility is the patients’ home, Garcia said. Patients are used to certain routines and expect certain care. Retraining nurses to provide that specific care can be frustrating for patients and nurses, she said.

The OHA said it has been, “working closely with ... hospitals, Colleges Ontario, the Council of Ontario Universities and the Ontario government, to understand the impact of the pandemic on health human resources,” and that it will take “appropriate measures,” to strengthen Ontario’s health human resources.

Grinspun said that before the pandemic, Ontario already had the lowest RN to population ratio among the provinces.

“We entered the pandemic with a [shortage of] 22,000 registered nurses compared to the rest of the country,” she said.

“Then layered on that, an extremely difficult and challenging pandemic ... [nurses] went to work every day, they gave it all.”

“Then, layer Bill 124 on that, and you have a complete disaster,” said Grinspun. She called the legislation a “slap in the face,” from a premier who does, “not understand the crisis of the situation.”

Bill 124, Protecting a Sustainable Public Sector for Future Generations Act, received Royal Assent Nov. 7, 2019. The bill imposed raises for public sector workers, including nurses, to one per cent a year for three years.

More than 100 physicians signed an open letter condemning the law. The Ontario Nurses' Association launched a Charter challenge, on the grounds that the bill interferes with nurses' right to free bargain.

While the Charter challenge continues, the law stands.

The province has delivered on a 10 per cent increase in nursing school enrolment, Grinspun said, adding that she was “pleased with that.” And yet, without improving conditions and decreasing the workload, she said, freshly trained RNs will move to other jurisdictions.

“We can recruit all we want. If we do not retain, nothing is enough … if we do not focus big time on retention, basically we are giving people expertise for them to leave for the U.S.”

I’ve been an RPN for 7 years. Cuts over the decades have nurses running off their feet just to provide subpar care. My hospital doesn’t have PSW’s to provide care its been incorporated into the nursing role. Ford said PSWs deserve a raise because how hard they work. OK what about us that now do both jobs?!?! I see medical stuff get missed all the time because nurses are busy showering, toileting, changing diapers, feeding, transferring patients to and from bed, cleaning rooms and making beds. Everybody makes mistakes but in nursing mistakes can have deadly consequences. Understaffing or heavy workloads cause nurses to miss stuff meaning people will die more often. Hospitals will blame it on health condition instead of what nurses really know, if we had proper staffing they might have survived. waiting 20+ mins for a nurse to answer call bell unacceptable, if they were choking they’d be dead. RPNs hit max pay after 2 years, so 2 year RPN and 30 year RPN make the same. High schooler can get RN in 4 years, RPN takes 3 years after 2 years of college and years of hands on experience. Talk about exploiting people trying to get a raise. Nurses are mini doctors and most patients won’t see their doctor till a nurse deems it necessary but the public treat us as hand holders. Most patients are shocked to find out how much nurses do and how they never see their doctor… everyday I think about quitting nursing but it was my dream. I have to admit its killing me inside. Im starting to hate Canada and our government. Terrified to end up in Canadian healthcare cause I know its off the backs of nurses.

Wow well said Robin, its disappointing and very true as to how they have exploited and down played a nurses worth. I believe Canada is actually trying to drive the healthcare system to the ground. Especially after bill 124. This is honestly a joke and I hope this all will change

It’s not “cuts” it’s that a purely public system always becomes increasingly inefficient until it becomes unaffordable. Healthcare is a HUGE expenditure in the Canadian budget. It’s that we aren’t getting the bang for our buck.

WELL SAID GARCIA IF FLORENCE NIGHTINGALE COULD ROLL OVER IN HER SHE WOUKD HAVE, THANK YOU FOR YOUR ARTICLE.