The COVID-19 pandemic has left thousands of Canadian charities in financial limbo.

Cancelling events for safety or flipping the virtual switch have created significant setbacks for charitable organizations trying to raise money.

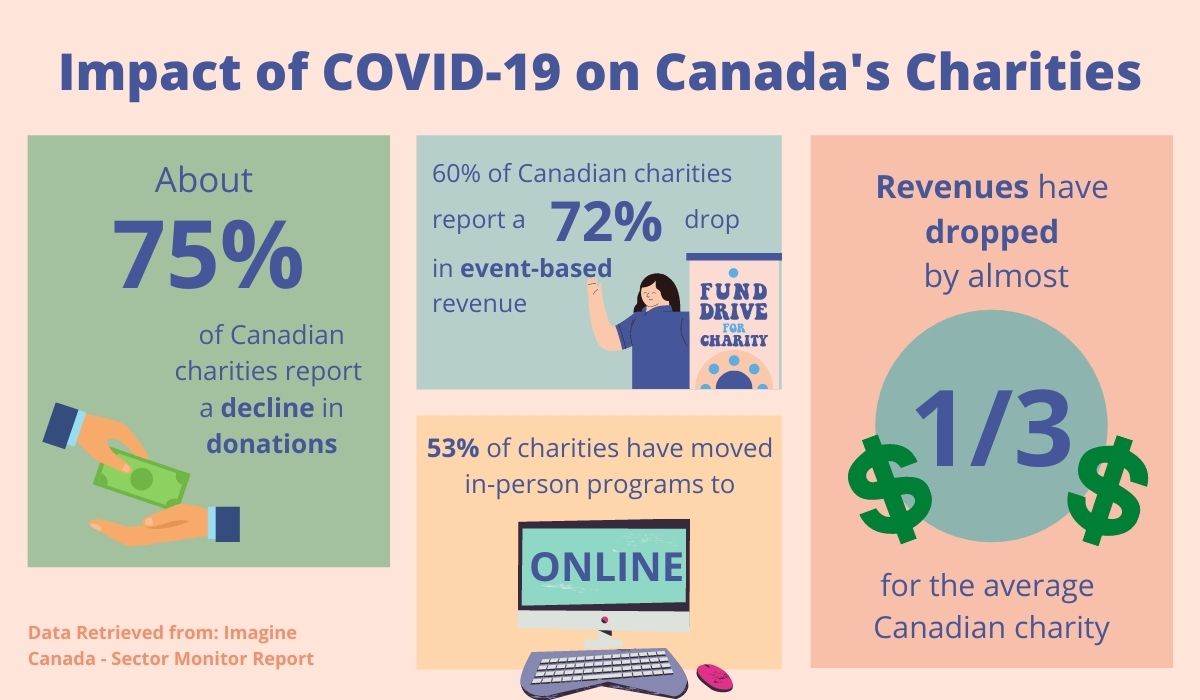

In May, almost 75 per cent of Canadian charities reported a decline in donations, and total revenues dropped by a third, on average, according to Imagine Canada’s Sector Monitor report.

There is a concern that if this downward slide continues, charities will not be able to provide the usual level of support to those in need.

Cathy Barrick, CEO of the Alzheimer Society of Ontario, says virtual events are collecting about half of the revenue that would typically be expected at an in-person fundraiser.

“Donor behaviour varies depending on the economic outlook, and particularly, how it affects them,” she says. “Many major gift donors give from their stock portfolio … and when the market falls, so does the availability of funds to donate.”

Job loss, or fear of job loss, is another factor Barrick highlights when considering changes in donor behaviour.

Barrick says it’s impossible to predict the exact impact this economic deficit will have on the Alzheimer Society, but continued drops in revenue will affect its ability to provide service.

“At least 50 per cent of our revenues for the Alzheimer Society come from fundraising,” she says. “Already we don’t have enough funding to meet demands.”

‘Well of need will deepen’

Continuing to provide support, despite fresh challenges, is the main goal of Mark Taylor, vice-president of resource development at United Way East Ontario.

Taylor says when COVID-19 arrived in Ottawa, it became clear more people would be in need of support, and already-vulnerable communities would be hit harder.

“No matter how generous and how supportive people are, when there’s more need, there’s going to be fewer resources to spread around,” he says.

Taylor’s biggest fear is that during community rebuilding, only certain groups will recover, and others will be left behind. For example, restaurant workers, taxi drivers and parents who rely on a strained child care system will be more vulnerable to the negative financial impacts of the pandemic.

Donations are also dependent on the broader economy. Taylor says about 10 per cent of United Way East Ontario’s regular donors have had to shift the timing or amount of their contributions this year.

[Photo courtesy Mark Taylor / United Way East Ontario]

Thankfully, he says, new donors have stepped up to contribute to areas of increased demand in response to COVID-19, which has prevented a large drop in their donations. However, it is unclear how long this will continue.

“Generally speaking, the philanthropic sector, of which United Way is a large part in Canada, estimates it may take in up to 20-per-cent less in personal and corporate contributions,” says Taylor.

Despite the unpredictable nature of the pandemic, Taylor says it has prompted United Way East Ontario and its donors to consider innovative ways to help the community, such as providing face masks to vulnerable communities.

Taylor has also noticed donors demonstrating extra generosity, for example, people donating despite being impacted by COVID-19 themselves.

He says media coverage of the pandemic has created a “shift in attention” and brought light to the work the United Way does in Ottawa. People want to be more engaged and help with community recovery, he says.

Thinking long-term

Lisa Sullivan, executive director of Hospice Care Ottawa, a charity that offers palliative and end-of-life services at no cost, appreciates extra generosity, but does not see it as a solution for the losses in fundraising.

“I don’t think it’s sustainable,” says Sullivan. “Over the long haul, if this continues, people just aren’t going to have the extra money.”

Sullivan says Hospice Care Ottawa has lost about 40 per cent of its fundraising revenue due to COVID-19.

“It’s really concerning,” she says. “We don’t really know how it’s going to affect us, but we have to start planning.”

If funds from donors or government support do not increase, Sullivan worries the charitable organization will need to restrict services.

Silver lining

In the face of economic uncertainty, stakeholders agree COVID-19 has shone a light on the need for charities to receive adequate government funding, alongside support from the community.

“It’s been a moment in time where people have the time to reflect on what’s important to them and give to those who need it,” says Barrick.

Taylor says COVID-19 has put extra pressure on Ottawans to notice an emergence of need in their respective neighborhoods.

“We’re not going to let that capacity and that capability that we’ve created as a result of the pandemic slide,” he says. “We’re going to capitalize on it, and use it to help our community.”