The COVID-19 crisis has locked us down and one result of the confinement is that citizens are putting out more garbage than ever before, according to media reports.

The crisis has also delayed public consultation on Ottawa’s new Solid Waste Master Plan, a 30-year strategy to be completed by the end of 2021 that would provide a framework for waste diversion from the Trail Road landfill.

The plan aims to expand the life expectancy of Ottawa’s main dump, which is expected to reach capacity by 2045.

How does our current waste management system work?

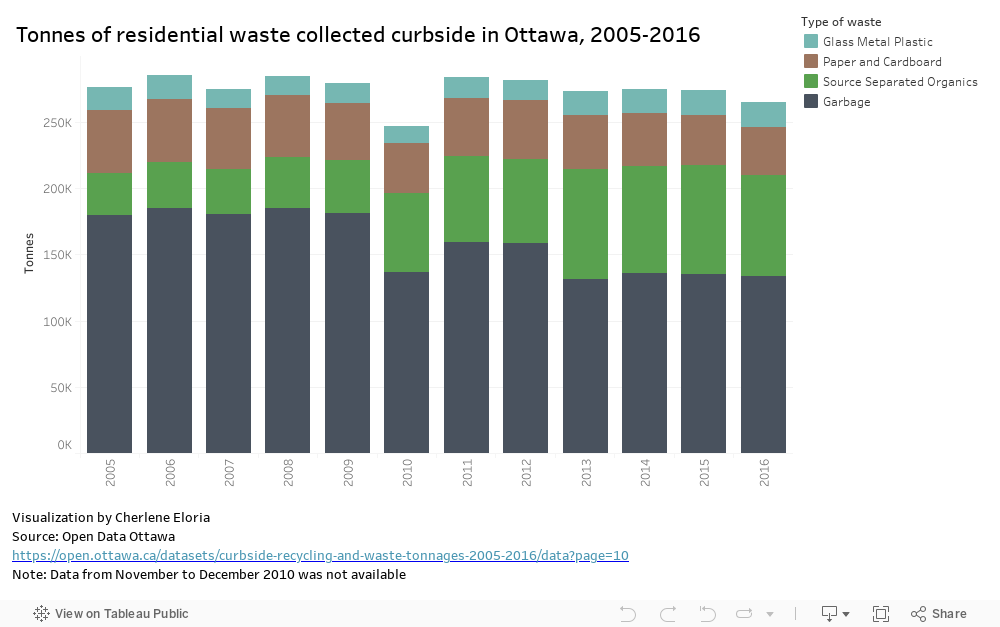

Ottawa, one of Canada’s largest cities by area, has 126 trucks travelling across 5,600 kilometres of roadway every week to collecting waste from 294,000 single family homes and about 1,700 multi-residential properties. According to the city, these homes generated 272,692 tonnes of waste in 2018.

Source: 2018-2019 City of Ottawa Curbside Residential Waste Audit Study

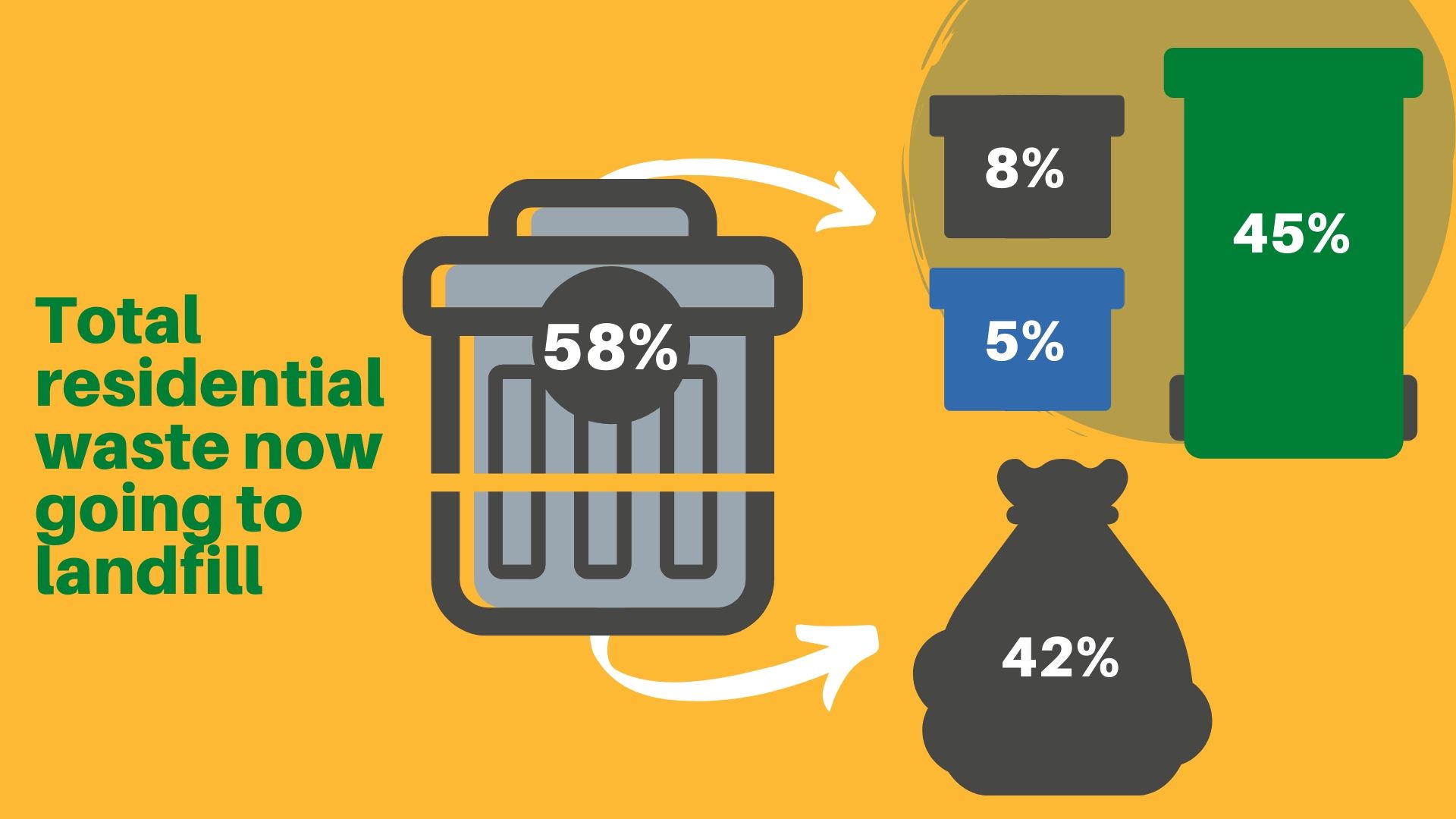

The city reports that 85 per cent of single family homes recycle. However, residents are putting far too much waste into garbage cans and trash bags that should be recycled instead.

In fact, 58 per cent of materials that are thrown out could be diverted from the dump through recycling and compost bins.

Source: City of Ottawa 2020 report: “Overview of the City of Ottawa’s Current Waste Management System”

Dr. Calvin Lakhan, a research scientist at York University says, “the people that are not participating in recycling are largely doing it because of inconvenience.”

He mentions a lack of awareness and impediments such as living in a multi-residential building as factors that prevent people from recycling and composting.

“People are good environmental citizens,” he says. “They want to participate with us, but if they even have the slightest impediment they’re not necessarily going to go way out of their way to do it.”

When it comes to Ottawa’s organics collection, the city has diverted more than 600,000 tonnes of compostable waste from landfill since 2010, according to a recent city report.

“When we talk about waste management, from a residential perspective, in a lot of instances we kind of only think about the blue box and historically other waste streams. Particularly organics has kind of been an afterthought,” says Lakhan.

What is waste diversion and why does Ottawa need it?

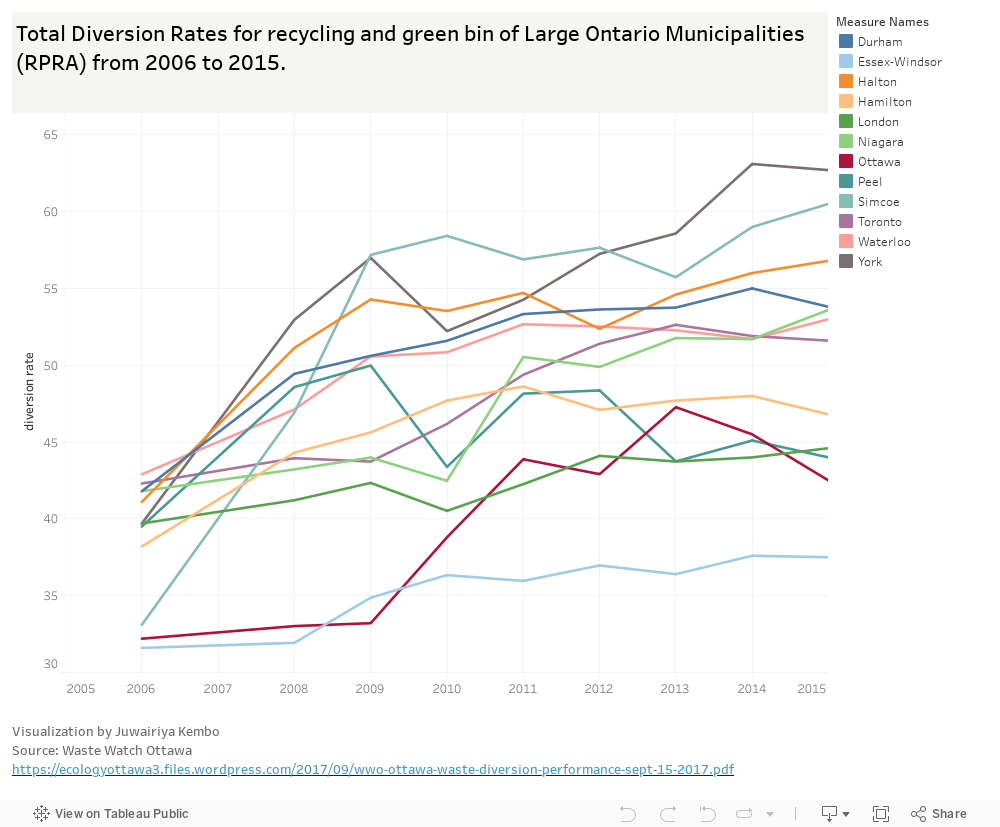

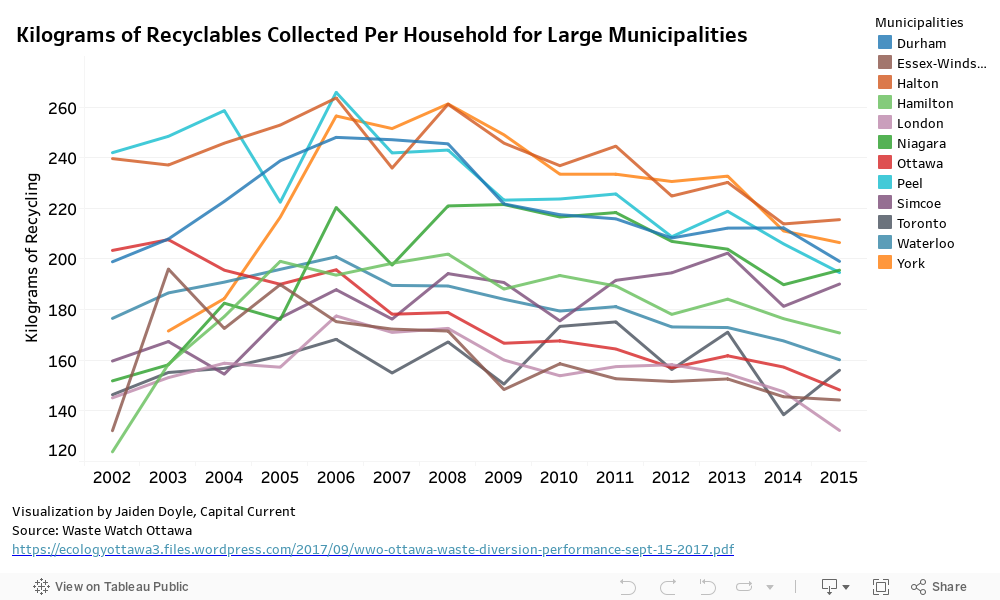

According to Waste Watch Ottawa, a volunteer group dedicated to environmentally sustainable management of the city’s waste, the municipality’s diversion performance falls well below that of comparable cities in the province.

Waste diversion, or landfill diversion, involves shifting trash away from landfills and thereby extending the life of dumps and delaying or avoiding the creation of new landfills.

A recent WWO report shows Ottawa’s waste diversion rate in 2015 was 42.5 per cent, or 5.2 per cent below the overall average of all municipalities.

“Clearly, diversion is the big goal here. What (the city) needs to do is maximize the amount of waste that gets diverted from disposal,” says Duncan Bury, co-founder of WWO.

The WWO report states that Ottawa falls short of the potential that is possible and demonstrated by better-performing recycling and green bin organics programs. Ramping up rates of recycling and composting could add decades to the lifespan of the Trail Road landfill, the organization argues.

The long-term consequence for Ottawa’s poor performance rates will be expensive.

In fact, according to a 2019 city report, the cost of building a new landfill is “in the hundreds of millions of dollars.” For instance, the City of Toronto purchased its current landfill in 2007 for about $220 million.

“If we diverted the level of waste and the amount of tonnes of organics and recycling as the leading municipalities in Ontario do, we could add 20 years to that capacity, which would take it to 2065, and that’s significant,” says Bury.

However, Lakhan says there are some issues with evaluating the success of municipal waste programs based on weight. For example, producers are increasingly switching to light weight materials which are not easily recycled in the existing system.

Instead, he adds, cities should focus on environmental goals such as carbon abatement.

“You can recycle less and achieve a better environmental goal in terms of carbon abatement or whatever it is by priorizing materials for recovery. And that’s something that’s been very absent from municipal thinking over the past decade,” says Lakhan.

Why create a Solid Waste Master Plan for Ottawa?

A Solid Waste Master Plan is being described by city officials and environmental advocates as a necessary step to help a municipality respond to future waste-management needs. It is meant to ensure the city operates a fiscally responsible, socially accepted and environmentally conscious system.

“I think the city recognized finally they needed to say, ‘Well, we really need to be aware of what the province is doing, but we have responsibilities to our own infrastructure and our own programs,’” says Bury.

WWO suggests that if Ottawa is to improve its current waste diversion performance, the life expectancy of the Trail Road landfill would be significantly longer.

With increases in population in coming years, Lakhan suggests promoting education for new Canadians who have never recycled before.

There’s a tendency to assume all Canadians recognize the universal loop-of-arrows symbol for recycling and what it means — but this isn’t the case, he says.

“More than 60 per cent of first-generation immigrants have never seen that symbol before.

“Municipalities should work with cultural and religious institutions in delivering that message,” he adds.

The City of Ottawa’s current planning process was launched in July 2019, when council approved a framework for the development of the Solid Waste Master Plan for the next 30 years of waste management.

Phase 1 ran until the end of March. This involved the city providing background information to the public to highlight some of the key issues. Phases 2 and 3, which include public consultations and drafting the final waste strategy, are to unfold between April 2020 and June 2021. However, delays are expected due to the outbreak of COVID-19.

City councillors are scheduled to vote on the plan in the last quarter of 2021.