Winter presents a slew of challenges for Ottawa’s growing homeless population and for the organizations across the city struggling to find shelter for them during the bone-chilling season ahead.

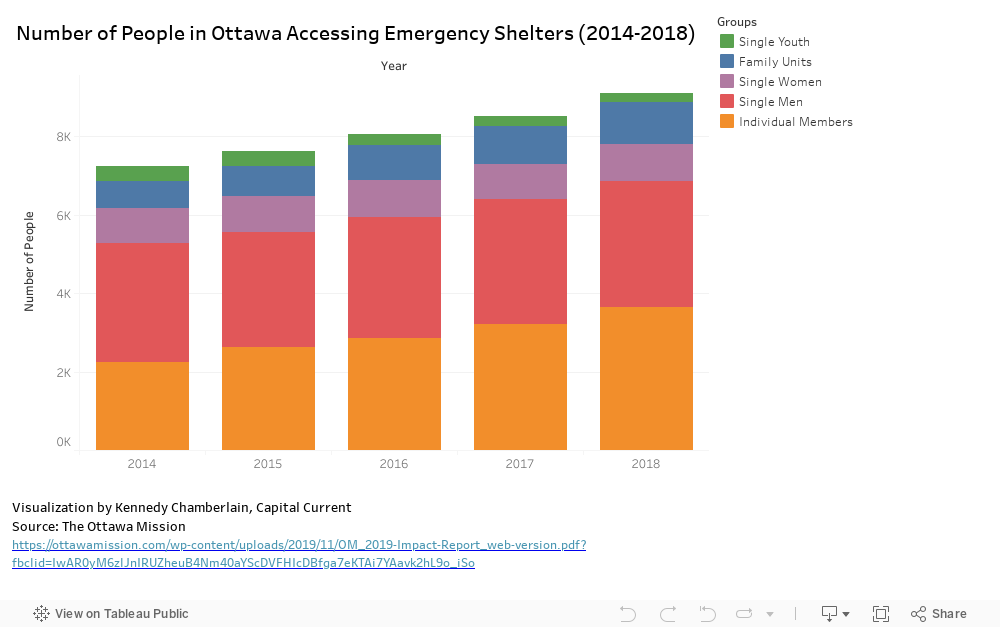

The city’s homeless population has been rising steadily in the last few years. According to the Canadian Observatory on Homelessness, 7,530 Ottawa individuals and families were reported homeless in 2017, up more than five per cent from the previous year.

One visible example of the challenge has been the tent city near LeBreton Flats. At the start of December, according to the CBC, about 10 people were still living in it.

Citing safety concerns, the National Capital Commission and the city of Ottawa warned the inhabitants recently that they would have to leave their makeshift shelter. That prompted tent city residents to hold a protest. Leilani Farha, the UN Special Rapporteur on the right to housing, said in a statement that the city of Ottawa, “should step up and must communicate with the residents directly to reach a human rights-based solution.”

The NCC has since formally told the tenters to leave the site.

In a joint statement, Somerset Coun. Catherine McKenney and Kitchissippi Coun. Jeff Leiper said all original residents of the encampment had been offered temporarily housing or motel rooms until more permanent housing becomes available.

The two councillors also urged all three levels of government to do better, stating “it is unacceptable that the only option for those without housing is to sleep on the streets or shelter.”

A statement from @JLeiper and me on the removal of the tent city. pic.twitter.com/28PCPfLJHV

— Catherine McKenney (@cmckenney) November 30, 2019

McKenney plans to table a motion with city council to declare a state of emergency on homelessness. Only a few weeks ago, Toronto Mayor John Tory did the same in his city. McKenney told 1310 News that the declaration would allow more levels of government to invest in emergency shelters and affordable housing.

We have “failed” those who slept outside or in shelters and “the situation will continue unless we treat this as an emergency,” said McKenney.

As the city struggles to cope, here’s a look at three of the many other organizations across Ottawa that help those with no roof over their head:

St. Luke’s Table

Helping the homeless is a key part of the mission for St. Luke’s Table, a ministry of the Anglican Diocese of Ottawa. The organization’s website describes its main goal as “[providing] a supportive environment where visitors can maintain and improve their personal and mental health.” Its programs range from meals for those in need, to counselling and social services.

St. Luke’s Table is run with the help of eight employees and 20 regular volunteers. The cold is the main challenge facing Ottawa’s homeless now, said Rachel Robinson, the ministry’s executive director. Yet despite the extreme temperatures, some people would rather sleep outside, she said.

“The reason they don’t want to go to the shelters is that they’re full. “Women in particular are very vulnerable when they’re in the shelters.”

The shortage of space in the shelters is part of why Robinson said she wishes the ministry had more resources so it could operate extended hours, “If we could open in the evenings and the weekend, it would help people in the winter for sure.”

Limited funds have not stopped St. Luke’s Table from helping those living in the Bayview tent city. The residents were displaced by fires in two rooming houses. The camp is relatively close to St. Luke’s Table, and, Robinson said, the ministry has acted as a drop point where people could leave donations – anything from sleeping bags and tents to propane and car batteries.

“We’re the venue for the donations, and there’s an outreach team at Somerset West Community Health Centre, which is taking the donations to the people [living] in the tent city.”

Shepherds of Good Hope

With more than 200 employees and hundreds of volunteers, the Shepherds of Good Hope organization provides food, shelter and supportive housing for some of Ottawa’s most vulnerable citizens.

Caroline Cox, senior manager of communications and community and volunteer services for the Shepherds of Good Hope, oversees the organization’s soup kitchen and its 500-plus volunteer program.

Cox said the organization serves as a stepping stone for those who turn to it for help. “A lot of people come to us, in my experience, not because of one thing that’s happened in their lives, but because many things have fallen through for them,” she explained. “Shepherds is often the last stop for them, but the first step towards rebuilding their lives.”

A lack of proper clothing is among the major challenges facing Ottawa’s homeless population, Cox said. When it comes to coats, boots, hats and mitts, “it’s been a scramble for people to try to get those things together.”

She added that “when people have mental health and addiction issues, they may be more vulnerable to being outside. They may need more people to look out for them if they’re intoxicated.”

One man who has benefited greatly from the Shepherds of Good Hope’s services is Irwin Kenneth Windsor. Originally from Bella Bella, B.C., Windsor spent four years living on the street in Ottawa.

Windsor, who struggled with alcohol, said he preferred the freedom of life on his own to the regulations of Ottawa’s shelters. However, he knows well the hardships of Ottawa’s extreme cold. “I was using two sleeping bags to sleep on and six sleeping bags over me in the wintertime” he said.

Now, Windsor is staying at the Oaks, a supportive housing residence run by the Shepherds of Good Hope. He said the organization’s rehabilitation program helped get him off the street.

“It took me a long time to get up here, that’s one thing, they weren’t going to take me up here for a while,” he described. “Until my best friend Guy, he was going to come here, but he said he wasn’t going to come up here unless I came. So, we both came up here together.”

Windsor said he looks forward to getting back into society. “I’ve started to learn from my mistakes, and I wouldn’t mind going back to school.”

Multifaith Housing Initiative

Staff at the Multifaith Housing Initiative (MHI) also know the challenges that winter brings. Suzanne Le, the organization’s executive director, said freezing temperatures can be deadly to someone unable to sleep indoors.

In Le’s words, “The shelters help homeless people survive winter. It can be the difference between life and death. However, what we need is housing for the homeless. They need permanent places to go. Places that they can be at all hours of the day, as much as needed.”

While the MHI is not a shelter, the organization owns and operates affordable housing at several properties. One example is Blake House, a 26-unit apartment building in Vanier that the MHI purchased in 2008. The building is one of four properties the organization owns. According to Le, these provide an option for those who are homeless and wish to move out of a shelter.

As a tenant of Blake House, Cindy Pothier said she has enjoyed her seven years living there with her 22-year-old son and an eight-year-old girl she has custody of.

Describing how she came to live there after spending time in a family shelter on Carling Avenue, Pothier said she thinks people with families, especially with children, get preference.

Pothier said she was lucky that she never had to live on the street, and she hopes Coun. McKenney’s proposed state of emergency has an impact on the city if it becomes official. “You have to really work at it and find out why there is such a long line for housing. Eight to 10 years for housing is ridiculous.”

–– Additional photos provided by Samantha Pope and Maryam Ammar, Carleton University School of Journalism.