Pandemic lockdowns prompted many Canadians to experiment with new hobbies as a way to cope with isolation. For some Ottawa artists, it was an opportunity to turn inward and put their deepest reflections on display.

Stay Silent, Drift Deep is the result. The exhibition at the School of Photographic Arts Ottawa (SPAO) features pieces about mental health by four local photographers. Each spent the summer creating as part of a student residency at SPAO. The result is rich in innovation and diversity with images of safe havens, self-portraits and even brain scans.

Exhibit curator and gallery program manager Darren Pottie said the pandemic has shed light on mental health issues across the nation. Working closely with the featured photographers during their residency, Pottie said the pieces produced show viewers different avenues they can take to work through struggles they may be facing.

“This exhibition tries to come to terms with mental health … to try and find something out there in the void that can help us overcome (struggles),” he said. “It’s all about fresh starts, maybe new directions, and kind of trying new things (to see) what else is out there.”

Though the pandemic has caused great mental strife for many, Pottie said it emphasized the importance of strong mental wellbeing. With the exhibit, he said, he hopes visitors will reflect on this new understanding and see themselves in the work.

“I hope they can start this process of looking outward and then looking inward as well,” said Pottie. “I hope people can see not just the portraits or the places and spaces on the walls, but see something reflected inside of them through their work.”

The SPAO exhibition runs until Dec. 19.

Meet Shaelynn Tredenick

Shaelynn Tredenick, 23, is an up-and-coming photo-based artist who has recently graduated from SPAO with prior experience in Algonquin College’s photography program. After dancing competitively for a decade, Tredenick now creates the same sense of movement in her visual art, which often consists of photographic scanographs of still life, plants and dried flowers.

Her featured piece, titled Knell in Blue No.1, is an illustration and depiction of a traumatic event she experienced about a year ago. She and her mother settled into a home together in Ottawa and her mom’s then-boyfriend visited regularly — however, when he came over, Tredenick said she witnessed “a lot of fighting.” These problems spiralled into a break-in and the subsequent flooding of their home, leaving mother and daughter with a lot of emotions to process.

“It was probably the worst thing that’s ever happened in my life,” Tredenick said. “The first time that I walked up to my front yard, I just saw my front-door-glass all over my front yard.”

The explanation of her work details the damage and how they found “vents stuffed with shirts, boards across the front and back doors, holes poked in the ceiling for water to run through, and finally a noose hanging in (their) staircase.” While no person died that day, the comfort the two once felt in their home did.

As someone with divorced parents, Tredenick spent a lot of time moving between her mother and father. She said the home she shared with her mother — before it was vandalized — gave her a sense of stability and made it feel like a real home.

“That house was the most precious thing to me. I just felt so comfortable. It was who I was and it was my mom and I. It was our safe house. And then someone just ripped that away from us,” she said.

After the home sustained more than $150,000 worth of damage, Tredenick and her mother spent the last year slowly picking up the pieces. One of the main ways she has reflected on this event is through photography, especially in her eye-catching contribution to the Stay Silent, Drift Deep exhibit. Her piece is a framed print of dried flowers in a dark setting, juxtaposed by shards of glass, suspended by fishing line, hanging in front of the image. Tredenick said she views it as a representation of herself and the inner turmoil she’s faced since the traumatic experience.

“The flowers just represent something so elegant, so soft,” Tredenick said. “That contrast of that sharp glass in front of your face (dripping) down from the flowers . . . was a perfect contrast. It also looks like rain; it’s just such a downpour of emotion.”

She added that although the combination of the flooded home and the COVID-19 pandemic suppressed her passion for art, she wanted to confront her trauma in the way she felt most comfortable.

“I kind of just said f— it to myself,” said Tredenick. “I said, ‘Work with what you’ve got, your emotions are still so fresh that you could pour even more into (your art).’”

Meet Steven West

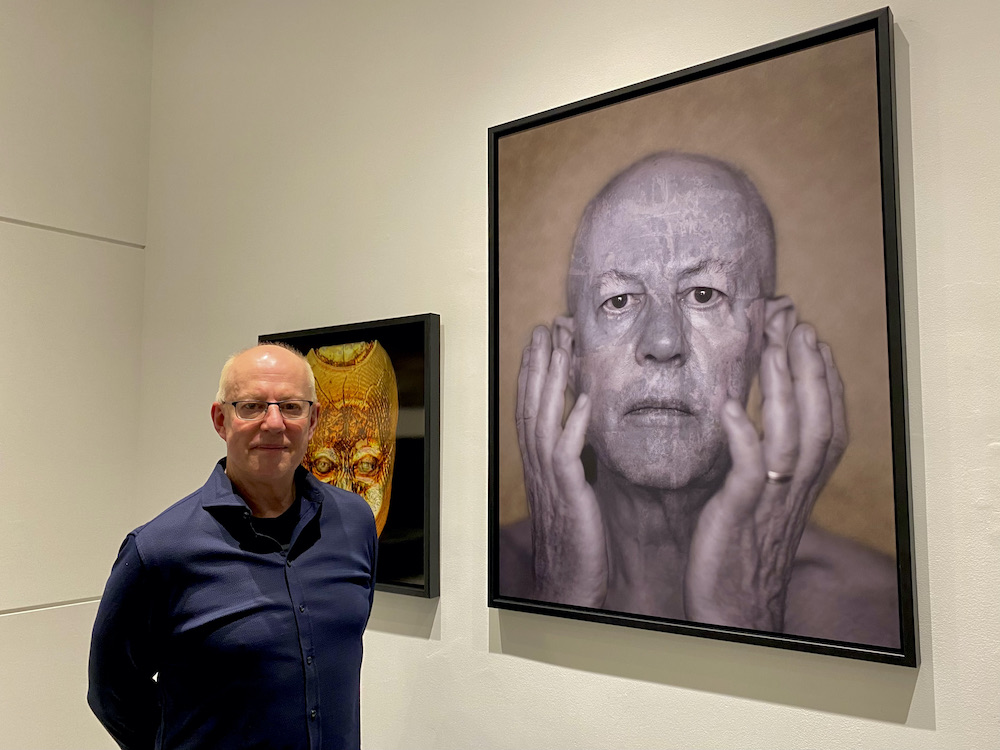

Steven West, 69, is a fine art photographer whose creations involve innovative, experimental combinations of photographs and science. Having spent most of his career in executive roles across the world, he decided to make a shift and pursue his interests in photography.

“It really was life changing for me because I came from health science and the business world,” West said. “I suddenly found myself in the artistic world, which was a huge transition. (It) took me completely out of my comfort zone.”

Science and technology has never left West’s work. Through his artist residency at SPAO, as well as his current position as chair of The Royal’s Institute for Mental Health Research board, West reflects on mental health by combining black and white brain scan X-rays, high powered digital imaging and photographic software. His contributions to Stay Silent, Drift Deep feature images of his own brain.

West said he hopes to create awareness around the importance of mental well-being through his work, because despite it being the most complex organ in our body, “we know very little about the brain.”

“We don’t fund research into mental health the way we fund research into cancer and diabetes,” said West. “I’ve been privileged to be part of The Royal to see the profound issues that society is struggling with when it comes to mental health.”

A silver lining from the pandemic is that it seems to have sharpened perspectives on mental health, he added. “There is nobody today that hasn’t felt uncomfortable,” said West. With his innovative approach to the fine arts, West said he hopes to normalize talking about that feeling of discomfort.

“I’m not creating art to hang up above the fireplace, that’s not my thing,” he said. “I want art that puts people outside of their comfort zone and makes them ask, ‘What is that?’ to have a conversation around.”

Meet Margo McDiarmid

Margo McDiarmid, 65, is a photo-based artist and former award-winning CBC broadcaster. After working as a journalist for about 35 years, her experience in filming videos and documentaries for The National in Alberta sparked her passion for digital storytelling and art. By 2018, she was ready to switch gears and applied to SPAO to pursue her interests in photography, but found that it wasn’t as easy as she initially expected.

“I was terrible,” McDiarmid said with a laugh. “My photographs were out of focus, I couldn’t figure out the darkroom, the printing drove me crazy. It was really frustrating and very stressful.”

Despite her initial struggles, McDiarmid said she found the experience to be humbling, particularly after a long career filled with successes. Three years later, she developed her skills enough to be comfortable with her work, which often focuses on documenting people’s interactions with empty and remote places.

The photographs featured at the gallery showcase six Ottawa ice rinks out of a total of 25 featured in a photo book she published titled The Outdoor Rink. She was interested in capturing the relationship between the city, which provides the electricity and boards, and the community volunteers, who perform general upkeep.

“I really wanted to reflect what those rinks mean to me,” McDiarmid said. “They’re cozy, reassuring and comforting, but I think they also helped to keep people safe last winter with the pandemic. They were a place where people could go and have some fun outside safely, so that’s what I tried to capture.”

McDiarmid said she hopes people experience the same feelings when looking at the rinks as she did, which is their special sense of beauty and significance within their respective communities. After collaborating with McDiarmid’s efforts to showcase the volunteers’ maintenance of the local rinks, The City of Ottawa was so pleased with the results it bought 300 copies of her book.

“I felt that project kept me sane for sure,” she said, describing that she was in the middle of renovating and selling a home which had been a great source of stress for her at the time. “It kept me occupied and focused, which is very helpful in a pandemic. I was able to connect with other people in a safe way, which you can’t if you’re in your home by yourself.”

Now a graduate of SPAO, McDiarmid said she’s proud of how far she has come and she looks at not only photographs, but life, in an entirely different way. She described that she sees things she never saw before and that her eyes are now opened to things a lot of people would typically miss.

“When I pick up a camera, I forget everything else,” she said. “I forget if I’m cold or hungry, everything that’s going on in my life. I just get into what I’m photographing and its a completely immersive experience for me.

“It’s almost like swimming, you’re in a different element. I think that’s what I like the most and it’s why I keep doing it.”

Meet Ava Margueritte

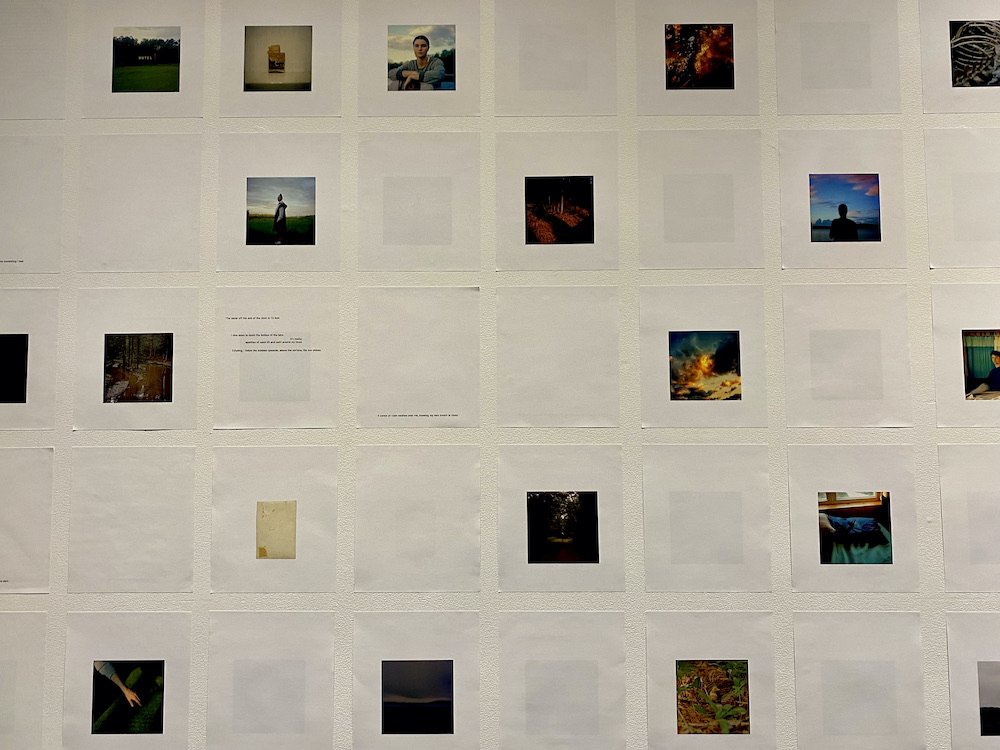

Ava Margueritte, 27, is a multidisciplinary artist who uses photography to explore the connection between body and mind. Her contribution to Stay Silent, Drift Deep is a deconstruction of her fifth self-published book, One Mile. The display is a visual diary that takes up a wall of the gallery’s main entrance, immersing visitors into her mind through pages of photos and poetry.

“While one image doesn’t give the whole story, among others it becomes intimate and an exploration of different emotions I’ve experienced and felt,” she said.

When the pandemic hit, Margueritte moved back into her family home. Given the circumstances, she said she felt a lot of anger and frustration, so she began a “meditative routine” through taking film photos on long walks.

“A lot of this past year was very reflective and I’ve had experiences that are difficult to unpack,” said Margueritte. “But through this process I’ve been able to unpack them a bit better. This body of work is a lot softer than my previous work, which stemmed from anger — this stems from acceptance and understanding that there is truth in my story.”

As a neurodivergent artist with dyslexia, she said she feels that a “text-oriented world” isn’t inclusive. By placing her photographs in a tangible book, she gives readers a more intimate experience with her work.

“With COVID, I experienced a lot of digital artwork and it just wasn’t doing it for me,” said Margeuritte. “I want to provide accessible artwork to my audience.”

She added that a major theme throughout her imagery is navigating feelings of control, which she feels is portrayed through the pages of her publications.

“A book is hyper-controlled and I’m able to portray the experience that I want you to (have). With a book, you can create a rhythm,” she said. “It’s an experience versus a moment.”

Many of the images in One Mile contrast with one another, which Margueritte said is due to her fascination with different forms of light. With around 600 photos shot for the project, ranging from self-portraits to a mouldy lemon, the batch she selected is diverse to carry readers through her experiences and have them reflect on their own.

“When people engage with my work, it should be about their experience and that’s how I connect with my viewers,” said Margueritte. “When it invokes something in (them), it creates this vulnerable moment of connection.”