Anouk Hoedeman stands before a vast display of meticulously placed bird corpses lying on the floor of Ottawa’s City Hall. She says she’s been a bird enthusiast for more than 25 years, and was devastated after a number of Bohemian Waxwings killed themselves after flying into a glass walkway attached to the building. “There were dead and dying birds all over the place. I thought, ‘this is really horrible. Someone should do something about this.'” That’s when Hoedeman founded the Safe Wings volunteer initiative, and began raising awareness about bird-friendly building design, with the help of a large group of advocates. “This is basically my full-time volunteer job.” [Photo © Adam van der Zwan]

Safe Wings has, for the past few years, held an annual display of dead birds. In March at City Hall, more than 1,600 feathered bodies, taken from the deep-freeze and categorized by species, lay in an ornate pattern on the floor. All died after slamming into glass around the city. They were unable to distinguish a window from the reality behind it. A notice at the front of the display says these birds represent only a fraction of the hundreds of thousands that die this way each year. [Photo © Adam van der Zwan]

The volunteers at Safe Wings have been monitoring dangerous buildings since 2014. In 2015 Safe Wings held their first dead bird display at the Canadian Museum of Nature. Many bystanders collect the birds and report them to Safe Wings volunteers, who bag the bodies and place them in a freezer. At the end of the year, the birds are sent to the National Wildlife Research Centre in Ottawa, where they’re frozen at -80 degrees, to kill any pathogens. After the annual display, some are donated to the Canadian Museum of Nature, others are sent to Carleton University and the rest are shipped to the Royal Alberta Museum. [Photo © Adam van der Zwan]

“A lot of people associate bird collisions with high-rise buildings in Toronto or New York,” says Hoedeman. But that’s not always the case. “It took us very little time to find out that this is a major, major problem in Ottawa.” Ottawa has a lot of birds. It sits at the junction of the Ottawa, Rideau and Gatineau rivers, which are all migratory bird routes, and the city’s many green spaces attract birds who need to rest or build their nests. Low-rise buildings and residences abound in Ottawa. These are the structures a bird would most likely slam into, says Hoedeman. Generally, small song-birds are the most vulnerable, as they use the stars and moon to navigate, though the city lights disorient them at night. [Photo © Adam van der Zwan]

Hoedeman says she’s been lobbying the City of Ottawa to create bird-friendly development guidelines for years. Toronto, a pioneer in bird collision research, was the first municipality in North America to develop and implement bird-friendly development practices in 2007. Amy MacPherson, a developer at the City of Ottawa, says her small team has been working on a set of guidelines for Ottawa since last year, but because of staffing changes the project has been delayed and won’t be completed until the end of 2019 at the earliest. Hoedeman isn’t satisfied. “We were supposed to see a draft last fall, so we’re really hoping to see something this year.” [Photo © Adam van der Zwan]

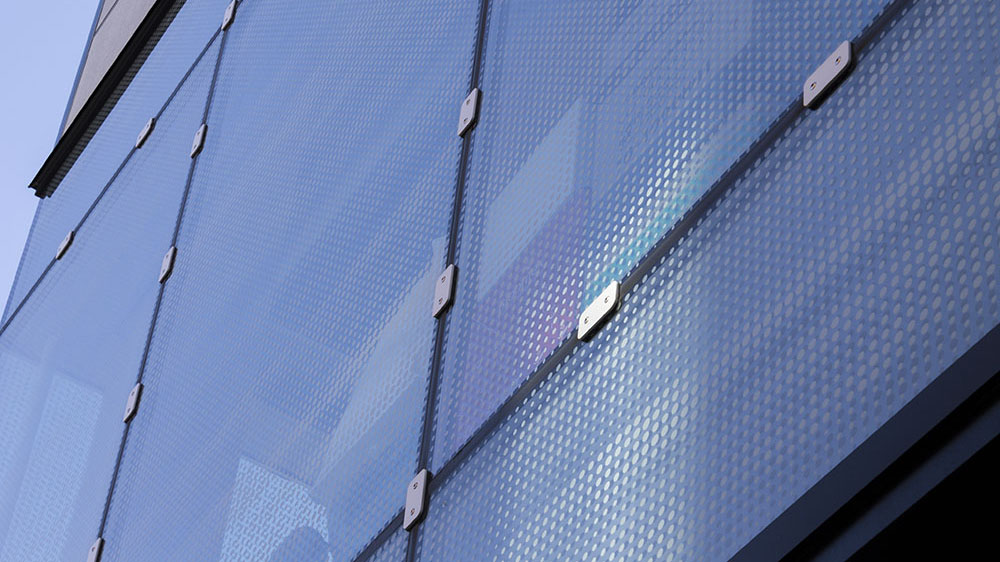

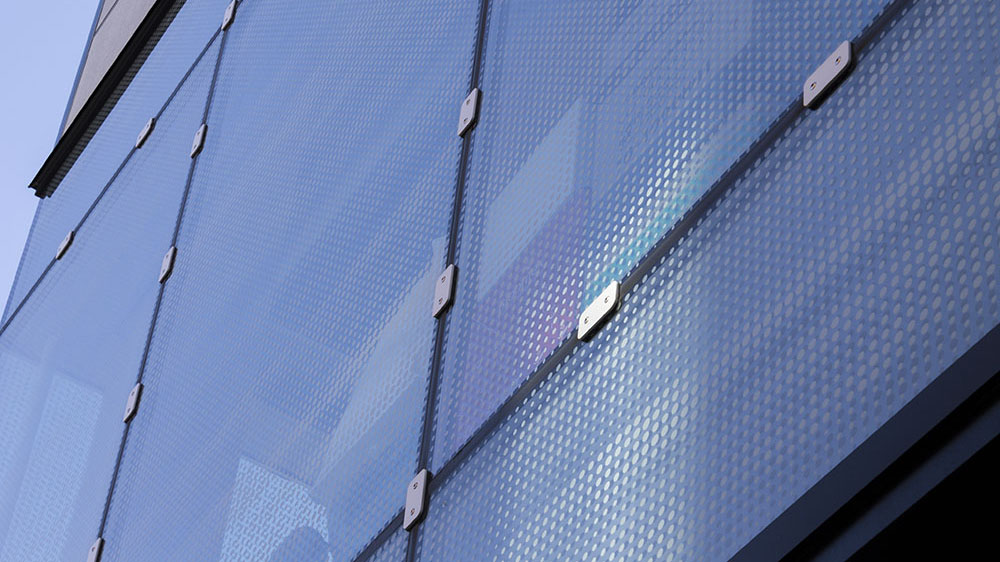

Toronto’s standard for a bird-friendly design recommends that builders adorn their windows with a visual indicator — a pattern of dots or decals — that help birds recognize a physical structure before they crash into it. Other markers could include “exterior screens, grilles, shutters, and sunshades.” While recent experimental designs have used hawk silhouettes on windows, research has found these to be ineffective, and instead suggests that visual markers be consistent and spaced no further than 10 cm apart, to deter the birds. In Ottawa, a number of newer buildings have already incorporated window designs, though not all have been effective. [Photo © Adam van der Zwan]

The new health sciences building at Carleton University, for example, has incorporated a dot-pattern on the lower exterior, that a Safe Wings web page says “would be more effective with a denser spacing.” [Photo © Adam van der Zwan]

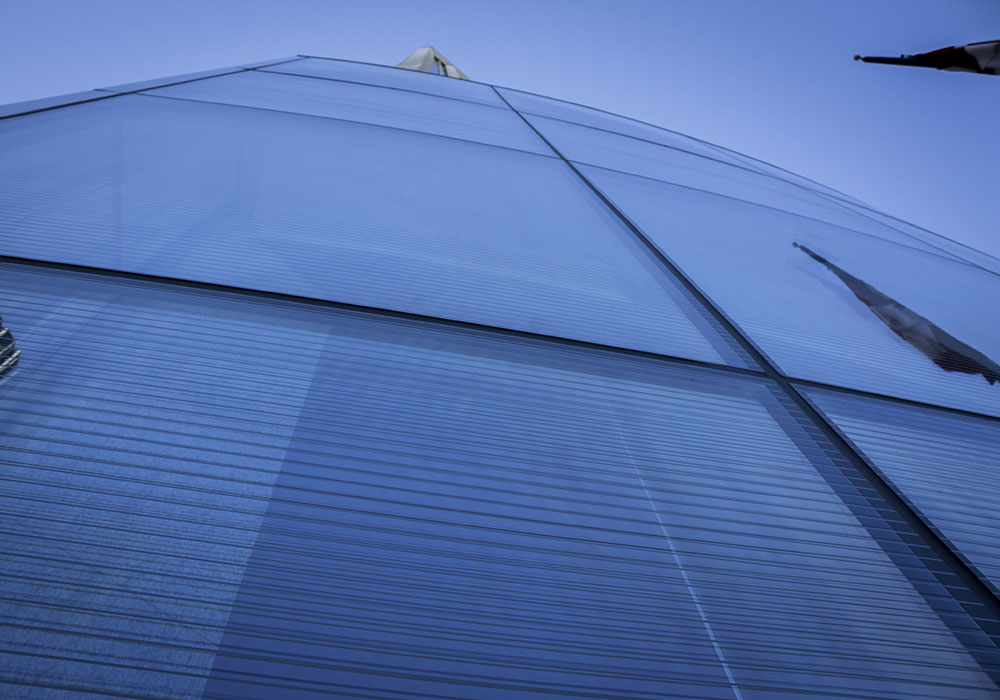

At Place Bell, on 160 Elgin St. across from City Hall, long white horizontal stripes run the width of the glass facade, which Safe Wings says have proven effective at deterring birds. “We haven’t found a single victim there,” their web page says. [Photo © Adam van der Zwan]

At the National Arts Centre, spacious markings — seen on the reflective glass above (right) — were etched onto the windows in 2017, and caused concern for bird advocates, who said the patterns were neither large enough nor dense enough to be truly bird-friendly. After studying Toronto’s guidelines, Jennifer Mallard, the project’s architect, created a “custom-tailored design” for the building. “We’re confident that what we’re doing here is the right thing to do,” she told the media at the time. [Photo © Adam van der Zwan]

Ottawa City Hall recently included a dot pattern on its suspended glass walkway, after numerous birds were found dead on the ground below. [Photo © Adam van der Zwan]

Anthony Leaning, an architect for 40 years, founded CSV Architects, a firm that focuses on environmentally friendly and sustainable design. “We’ve been aware of [Toronto’s] bird-friendly guidelines for sometime here,” he says. “It’s a great initiative.” [Photo © Adam van der Zwan]

In 2017, Leaning’s firm designed the new International Pavilion, a National Capital Commission building in the Byward Market, which “replaced an old stone building that had been condemned because the mortar was falling apart,” Leaning explains. The re-design aimed to meld modern architecture with the historical elements of the surrounding buildings. After the NCC suggested a bird-friendly design, the CSV architects created a dense pattern resembling limestone on the office windows above a retail store. While the pattern was lauded by bird advocates, to date this is the only bird-friendly project Leaning’s team has worked on. Apart from budget restrictions, he says “the culture still just isn’t there,” but he predicted it won’t take long because “humans are very adaptable.” [Photo © Adam van der Zwan]

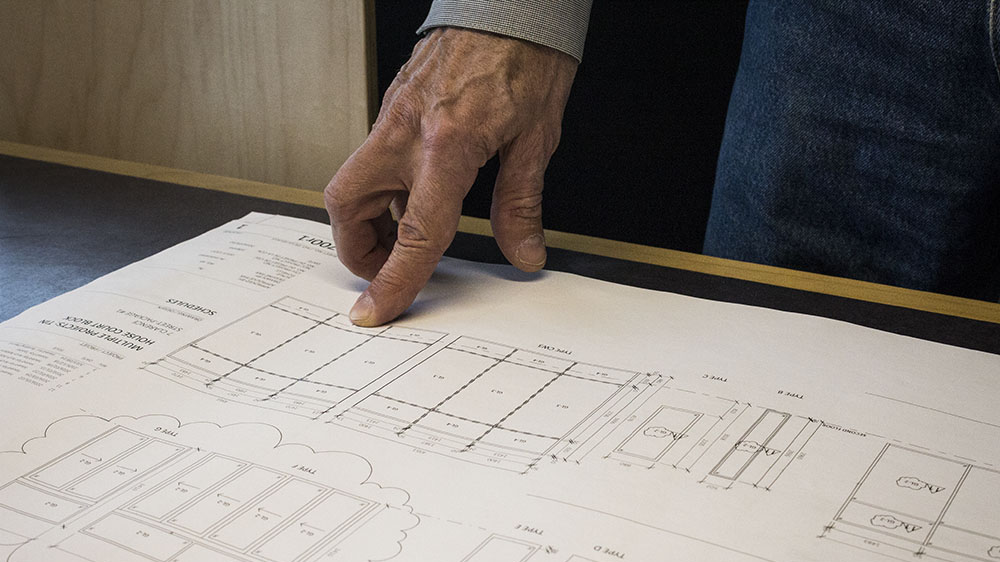

Leaning is seen here observing the plans for the newly designed NCC building. “We’ve done one building, and we should be doing every building,” he says. Leaning added he hopes the large, glass stations on Ottawa’s new O-Train Confederation Line will include bird-friendly designs. Currently, though, no patterns can be seen on the glass at various locations. Amy MacPherson, with the City of Ottawa, says her team has been trying to encourage OC Transpo to incorporate bird-friendly development. [Photo © Adam van der Zwan]

“What would be great is if [bird-friendly development] was mandated by law,” says Leaning. Like in Toronto, the guidelines that the City of Ottawa hopes to release at the end of the year are just those — guidelines. MacPherson explains that as something like this gains popularity and more people begin to see it as important, the guidelines could then become part of the building code. [Photo © Adam van der Zwan]

Until then, Anouk Hoedeman encourages Ottawa residents to adopt bird-friendly patterns on their home windows, and suggested products like Feather Friendly window tape. “People always worry that it might ruin their view, but it’s actually very subtle,” she says, adding that the human eye becomes used to the consistent pattern of dots on the window, and learns to look through them. “It’s incredibly effective at preventing needless deaths.” [Photo © Adam van der Zwan]