The number of homeless cats in Ottawa has reached crisis levels, with the Ottawa Humane Society having to euthanize more than one in three felines admitted to the shelter last year — double the national average.

In 2017, 32 per cent of the cats admitted to the Ottawa Humane Society were put down, according to the the shelter’s annual report. In 2018, the euthanasia rate rose to 36 per cent. The national euthanasia rate for cats is 18 per cent, according to Humane Canada’s 2017 Cats in Canada report. However, according to OHS’s latest annual report, all healthy cats were adopted in 2017-2018. The ones that were euthanized had serious health problems or other issues.

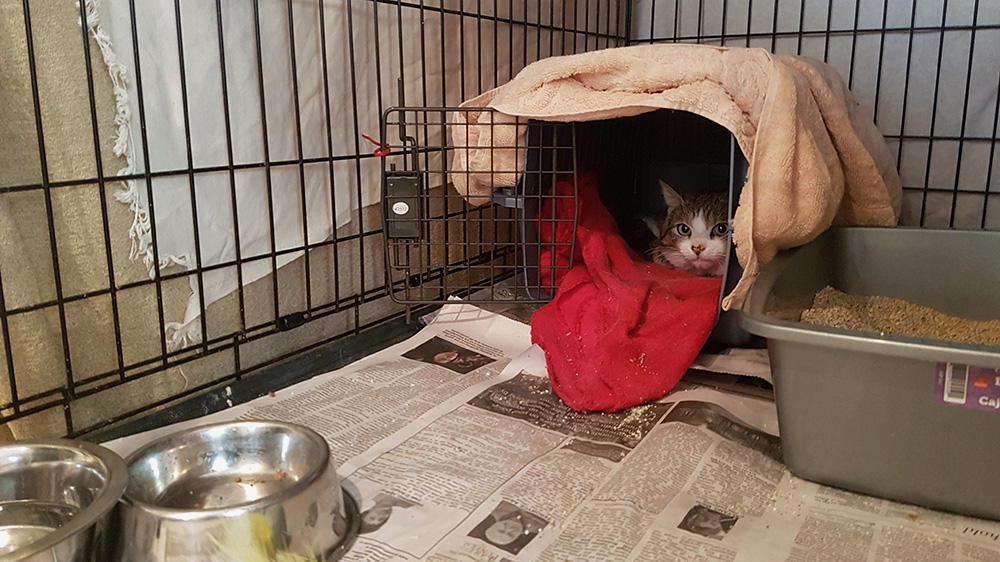

Claire Castell, Ottawa Stray Cat Rescue’s trap-neuter-release (TNR) co-ordinator, said a lack of space and resources has left the Ottawa Humane Society with few options outside of euthanasia for feral cats. She said this has been devastating for the animal welfare community.

“They just don’t tell people, and I kind of wish they would,” she said of the deluge of cats who have to be put down. “They do euthanize a lot of cats, but it’s not because they want to. They just have too many.”

The Ottawa Humane Society would not agree to an interview with Capital Current.

Despite statistics showing Ottawa significantly exceeds the national average for euthanasia, Alison Sandor, public information officer for Ottawa bylaw says there is “no evidence to demonstrate that Ottawa’s cat population has increased significantly in recent years.”

However, the Ottawa Humane Society’s annual reports showed an increase in numbers last year. In 2018, the shelter took in 4,980 cats and kittens — 257 more than in 2017. Castell says Ottawa’s cat rescue organizations took in an additional 4,000 cats last year.

Only the cats admitted to the Ottawa Humane Society are reflected in the city’s cat population numbers because Ottawa bylaw is not responsible for transporting and holding cats for independent rescue organizations.

Castell said this demonstrates a real “disconnect” between the animal welfare community and the city. She said 2018 was “the worst year for kittens being born outside” and needing homes.

“Hopefully we reach a tipping point where suddenly it goes down again, but right now, I just don’t think it will,” she said.

With little help from the city, Castell says the problem is only going to get worse this spring.

Typically, shelters and cat rescue organizations see a spike in the number of kittens admitted to their facilities between March and June.

This phenomenon, known as kitten season, is a consequence of feline biology, says Toolika Rastogi, policy and research manager with Humane Canada — Canada’s federation of humane societies and SPCAs.

Cats’ reproductive systems react to changes in sunlight. As daylight hours increase, more and more female cats begin to breed. And while a city swarming with kittens may sound adorable, it is anything but for rescue agencies.

“In areas of overpopulation, where you have shelters that are managing at a certain level throughout the winter, we see influxes in the spring and summer,” Rastogi said. “We see shelters getting overrun.”

For instance, last August, the Ottawa Humane Society declared an internal “kitty crisis,” when it was caring for more than 500 cats and kittens in a matter of days. In 2017, they received around 800 cats and kittens during kitten season.

Judith Aubin, senior spay/neuter services manager for the OSPCA, said that for shelters, the problem with kitten season is not necessarily the kittens.

“The kittens do get adopted pretty easily. Unfortunately, sometimes they take the space of the adult cats who would have otherwise found a home,” she said.

This can lead to capacity issues year-round for rescue agencies, Aubin said, as adult cats wait longer to be adopted than kittens. According to the 2017 Cats in Canada report, on average, cats spend 20 days in a shelter or 44 days in a foster home before being adopted.

This has been the case in Ottawa, said Castell, where adoption numbers remain low for mature cats and many more are abandoned or go missing.

Of the 4,723 cats and kittens the the Ottawa Humane Society admitted in 2017, only 2,969 were adopted. While this number was slightly above the national average in 2017, where 64 per cent of cats admitted to shelters were adopted, the Ottawa Humane Society’s adoption rates fell from 66 per cent in 2017 to 62 per cent in 2018.

In addition, 4.7 per cent of lost and abandoned cats were reunited with their owners after arriving at the Ottawa Humane Society in 2017, compared to six per cent nationally.

“We don’t have the manpower, the finances, the foster homes, the everything,” Castell said. “We just don’t have the capacity.”

According to Humane Canada, large-scale sterilization programs can help to increase shelter capacity by reducing the number of unwanted cats born each year. In 2017, 87,737 cats were admitted to Canadian shelters — a 26 per cent decrease from 2012.

Aubin said her organization has seen similar results in Ontario.

“We can see the positive impact it’s having, because we’ve seen our shelter intake at the OSPCA go down since our [spay/neuter] clinics opened,” she said. “If done properly, it can be very successful.”

But Castell said too many Ottawa cat owners are not sterilizing their cats, which she says is behind the “exponential growth” she sees in Ottawa’s cat colonies during kitten season.

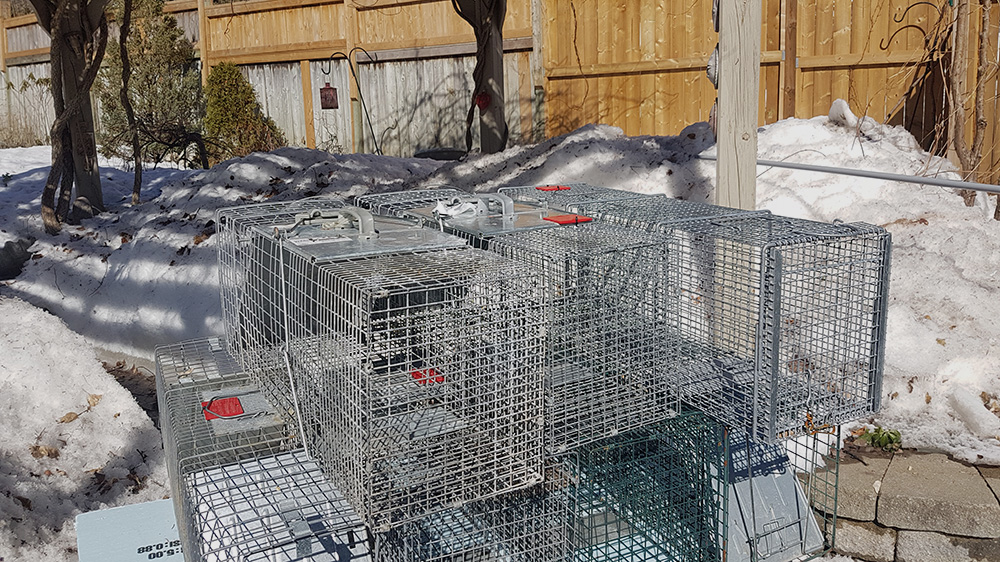

Ottawa Stray Cat Rescue manages Ottawa’s feral cat colonies through their TNR program, a population-control strategy that involves trapping and sterilizing mature cats to prevent them from breeding.

Nearly 800 colony cats were sterilized through their program last year, Castell said. The Ottawa Humane Society has sterilized an additional 3,300 domestic and feral cats since they launched their mobile sterilization clinic in 2016.

In comparison, the OSPCA responded to 6,959 sterilization requests province-wide in 2017—only 183 were for feral cats. This is down from 2016, where they performed 8,951 sterilization procedures.

Shane Bateman, a veterinarian who researches feral cat colonies at the University of Guelph, said this demonstrates the limitations of a sterilization-only approach to managing cat populations.

“There’s not going to be a one-size fits all or one silver bullet that solves this,” he said. “Finding like-minded stakeholders from animal welfare work, from nature conservancy work, from scientific research work, from local leadership . . . all those people need to come together around the table.”

But for this to happen, Bateman said local communities need to start caring more about cats.

“We’ve chosen to overlook cats. It takes a lot of conversations and a lot of people working hard to change minds and hearts,” he said.

“Cats are just treated like vermin and euthanized at huge rates,” Castell added. “I just can’t understand it.”

Note: This article has been edited to clarify that the Ottawa Humane Society finds homes for all healthy cats, according to its latest annual report. The cats that are euthanized fall into other categories, such as those that are seriously ill or feral.

Why can’t it be the law for pet owners to spay or neuter all their pets whether dogs and cats? That’s why there is no population control and they become feral!! AND the prices for spay n neuter and vaccines are too high!

Anyone who would like such a companion should not have to be wealthy to afford it. It’s plain stupidity and money hungry vets. Canada should be ashamed that they have not progressed rather regressed.

Ownership should involve mandatory neutering unless you pay for a licence to keep them intact. The government should sponsor free clinics several times a year because a lot of intact animals are that way due to cost. Fines should be issued for intact, unlicensed animals.

How do I organize a cat shelter in my area? There are too many cats roaming around, and it is getting cold. Any information about funding will help.