As the federal government prepares to ban plastic bags in its plan to achieve zero plastic waste by 2030, experts warn single-use alternatives like paper can be just as destructive to our planet.

For decades, scientists have sounded the alarm that plastic bags don’t only end up as harmful waste in landfills and the ocean, but they also shed toxic microplastics into ecosystems and infiltrate food webs.

Though the federal government has taken strides to cut back on this waste, experts say the production of paper bags — a popular alternative to plastic — is just as destructive. Switching to paper comes with a host of other environmental concerns, explained Sarah King, head of Greenpeace Canada’s Oceans & Plastics campaign.

“We are deeply concerned about the government’s failure to make it clear that alternatives need to be reusable and that we should not be switching from one type of product that fuels the climate crisis to another,” she said. “Instead, we should really be looking for reusable options.”

Even before the government ban on plastic bags comes into effect, big chain grocery stores like Sobeys are already taking measures into their own hands. In January, Sobeys removed plastic bags from all its stores, taking 225 million plastic grocery bags out of circulation each year.

Other grocery stores were way ahead of the game, such as Whole Foods. It eliminated plastic bags in 2008. As an alternative, paper bags have been made available to customers at both stores, among many other stores across the country.

But since plastic grocery bags are thin and light, their production actually generates less environmental impact compared to paper bags, according to a 2017 study by Recyc-Québec, a Quebec recycling group. The use of fossil fuels and the emission of fine particles and chemicals during paper bag production is of particular concern, the authors wrote.

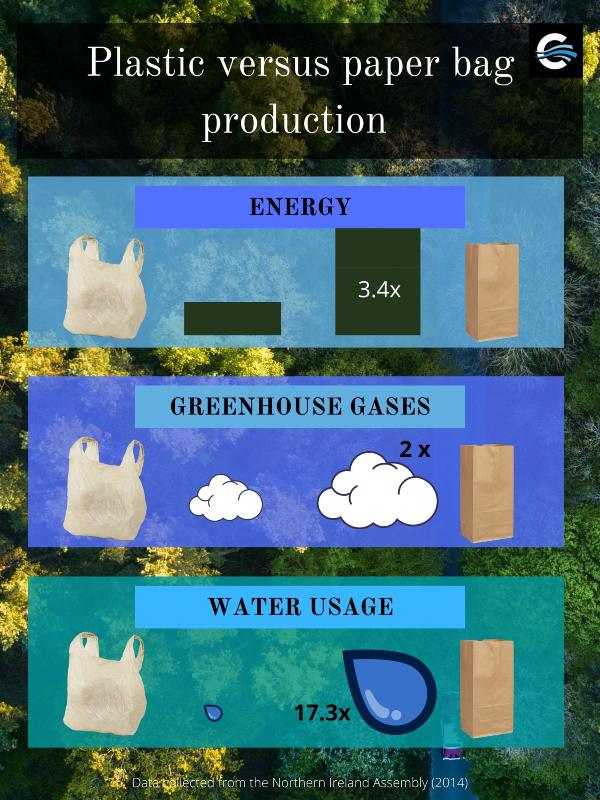

It also takes more than four times as much energy to manufacture a paper bag than a plastic bag, according to a widely-cited 2011 research paper by the Northern Ireland Assembly.

“For paper bag production, forests must be cut down and then the subsequent manufacturing of bags produces greenhouse gases,” the authors explained, adding that the majority of paper bags are made by heating wood chips. “The use of these toxic chemicals contributes to both air pollution, such as acid rain, and water pollution.”

Though paper does break down and can be recycled and composted, it takes 91 percent less energy to recycle a plastic bag than a paper bag, the researchers noted.

When the Canadian government announced its plastic waste plan, it did so with the intention of protecting wildlife and our waters, reducing greenhouse gas emissions and creating jobs, according to Environment and Climate Change Canada spokesperson Chelsea Steacy. But the department acknowledges that people still need bags to pack groceries.

“The (government) will work to ensure that items identified for a ban or restriction can be replaced by readily available alternatives that can serve the same function,” she said, specifying that this could include single-use alternatives like paper bags and reusable alternatives, like durable plastic or canvass.

“Differences in cost are an important factor to consider in developing regulations and analyzing (their) potential impact on Canadians and businesses,” said Steacy, referring to the potential rules on both single-use plastics and their alternatives.

Though consideration is being given to the environmental impacts of alternatives, Steacy said banning paper bags is not on the government’s radar as they are “not items with high prevalence litter audits.”

Despite the government’s tolerance of other single-use alternatives such as paper bags, King said this is the last thing people should be supporting.

“We should be looking at reusable options that originate from a sustainable, socially responsible source — non-toxic materials that can ultimately be kept in a loop,” she said. “We need to look for ways to deliver our products and services that aren’t reliant on fossil fuel-derived materials.”

Ideally, people should use bags they already have as an alternative, King said. People can also make their own bags out of material they already own, and then continue to reuse that when they go shop for groceries.

When it comes to companies, often a switch will be made to paper-based and bio-based alternatives. However, King encourages companies to take that extra step and create “a new reuse model that is healthier for the planet, for our communities, and ultimately for ourselves.”

Moving forward, the government needs to be incentivizing and investing in systems that are more focused on reuse models, King said.

“We need to constantly ask ourselves whether there are reusable options that can be used instead of disposable ones. Right now, our biggest concern is that there’s just no talk about these models,” she said. “We have a really, really long way to go.”