The Ottawa People’s Commission on the Convoy Occupation has released part one of its planned two-stage report on last year’s truck blockade in downtown Ottawa, describing what happened as a “human rights failure by all three orders of government and police” in response to the “violent” protest.

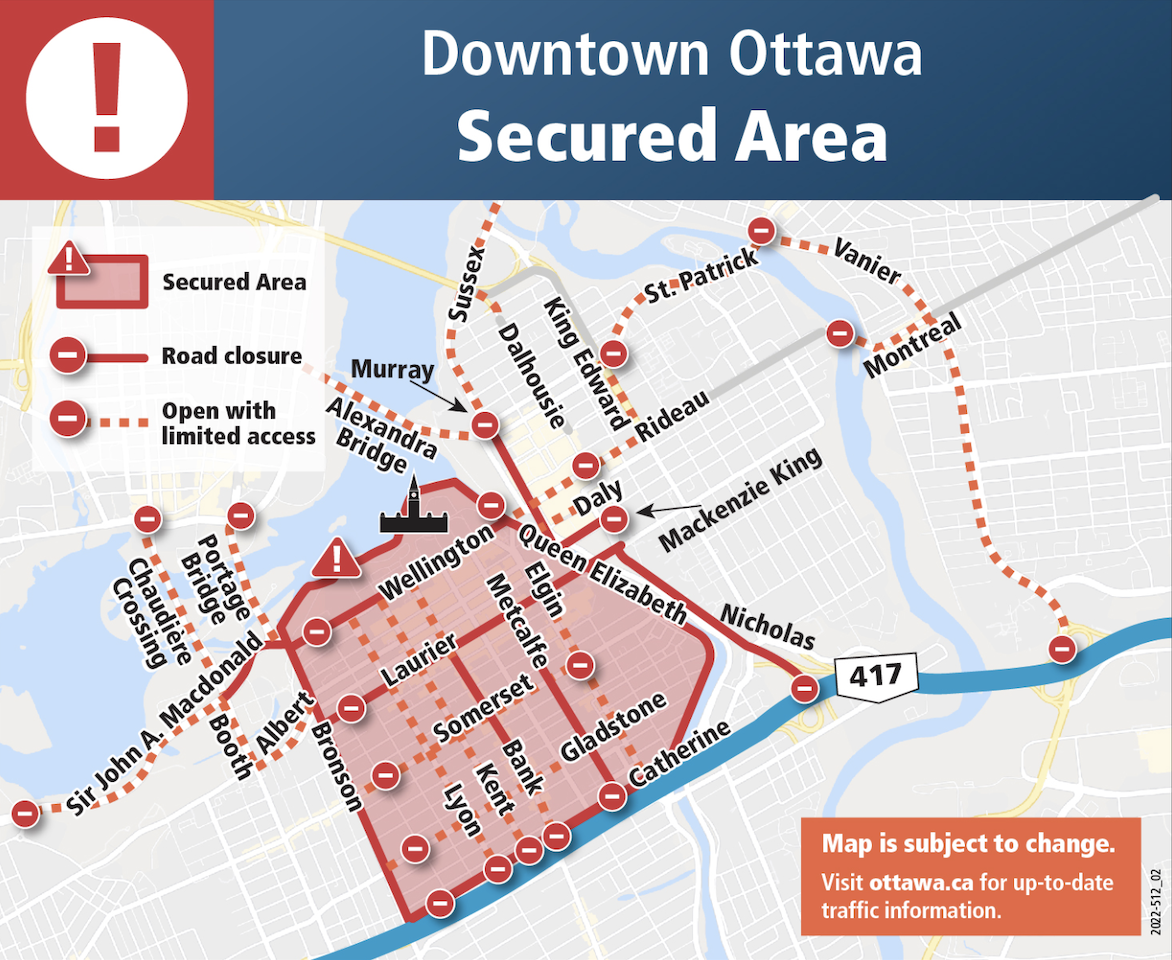

The downtown occupation severely disrupted the lives of those living in Ottawa. At this time last year, all streets in the core were closed following the arrival of hundreds of convoy vehicles. Blockaded streets were described as “a red zone” and were off-limits to local residents for much of February.

The commission report titled What We Heard was released Jan. 30 during a press conference at the Centretown Community Health Centre, which formed and administers the commission. The release marked one year since the beginning of the occupation by convoy supporters in response to a COVID-19 vaccine mandate for cross-border truckers and other pandemic restrictions.

The report was the culmination of 14 hearings, eight community consultations, and more than 75 written submissions. It recaps the experience of more than 200 Ottawa-Gatineau residents in a bid, the commission said, to bring healing as well as accountability.

‘Often, we heard (from) some media and politicians that the Ottawa convoy was a ‘peaceful’ protest. On the ground and from a majority of residents affected by the convoy, the description was the opposite. Many of the residents experienced physical, verbal, and mental violence.’

— Dr. Monia Mazigh, commissioner, Ottawa People’s Commission on the Convoy Occupation

The report documents the occupation of the downtown core, the violence experienced by downtown residents, the sense of abandonment felt by Ottawa residents and the mobilization of the community in response to the three-week blockade.

The report also presents testimony from some supporters of the convoy.

“In the absence of much-needed leadership from decision-makers, residents mobilized to create new networks of care: getting essentials for the vulnerable, organizing safe walks, and sharing vital information on how to navigate the new challenges faced while living in and around downtown,” said Commissioner Debbie Owusu-Akyeeah, a long-time social justice advocate and executive director of the Canadian Centre for Gender + Sexual Diversity. “Most importantly, people mobilized collectively to reclaim power many had lost as a result of the ongoing occupation.”

Residents described experiencing human rights abuses, threats, fear, sexual harassment and intimidation fuelled by racism, misogyny, antisemitism, Islamophobia, homophobia, transphobia and more.

“There was so much that went wrong and was overlooked during this occupation. There was so much hate and violence on display,” said commission witness Sheldon Kiishkens Ross McGregor, a member of the Kitigan Zibi Anishinabeg First Nation near Maniwaki, Que., in one of many excerpts published in the report.

‘There was so much that went wrong and was overlooked during this occupation. There was so much hate and violence on display. … This should not have happened. We must learn from this experience. We must listen to the people who went through it. We must make changes so that we do not go through something like this again.’

— Sheldon Kiishkens Ross McGregor, OPC witness, Kitigan Zibi Anishinabeg First Nation

“It was upsetting for our elders to see such disrespect for our ceremonies and for the protocols that are to be followed in our territory,” McGregor stated. “There was so much misinformation. Communication was poor and people were so fearful. This should not have happened. We must learn from this experience. We must listen to the people who went through it. We must make changes so that we do not go through something like this again.”

According to another commissioner, human rights lawyer Leilani Farha, “the gravity of what happened in Ottawa when the convoy arrived, and stayed, is found in one word: occupation. Many residents didn’t experience this like a regular protest; they felt their city had been invaded and was under siege.”

Author and social justice activist Monia Mazigh, also an OPC commissioner, added: “Often, we heard (from) some media and politicians that the Ottawa convoy was a ‘peaceful’ protest. On the ground and from a majority of residents affected by the convoy, the description was the opposite. Many of the residents experienced physical, verbal, and mental violence. The violence they went through was unbearable.”

The OPC’s key initial conclusion was that all three orders of government and police were responsible for the human rights failure that took place during the occupation of the city.

Though most residents who testified had strongly negative reactions to the occupation, some witnesses heard by the OPC praised the blockade.

“I received free hugs, hot dogs and hot chocolate. I saw supporters, teachers, farmers, doctors, and nurses hand in hand cleaning up the streets, feeding the homeless, and giving out free haircuts,” a woman identified as Christine is quoted saying in the report. “I witnessed one lane for emergency vehicles being kept open at all times and I was given free earplugs. Never once did I feel unsafe due to the freedom convoy. In fact, I felt a sense of pride and hope in my country that I haven’t felt for in a long time.”

But Alex Neve, a human rights lawyer and one of the OPC commissioners, described how most downtown residents’ experience was “to be stripped of dignity. It is absolutely to feel abandoned.”

The 72-page report captured Ottawa residents’ opportunity to be heard and understood. Part II of the commission’s findings are to be released in in March. It will continue the discussion about those who welcomed and participated in the convoy, offer a fuller analysis of events and propose relevant recommendations.