A report on the City of Ottawa’s response to last May’s hugely destructive “derecho” wind storm has highlighted gaps in emergency preparedness, including the way municipal officials support citizens with disabilities and ease food insecurity in a crisis.

The “after-action report” assessing the city’s response to the extreme weather event was given to the city’s emergency preparedness and protective services committee on March 30.

Among other things, the report looked at the effectiveness of the municipal emergency plan. While the plan was deemed quite extensive, the severity and unexpectedness of the derecho exposed gaps in the blueprint for managing a major natural disaster.

“Unfortunately, we can’t have all the answers for every potential type of emergency. We’ve never seen a derecho before — this was unprecedented,” said Kim Ayotte, general manager of the city’s Emergency and Protective Services.

A derecho is a long-lasting thunderstorm, characterized by extensive wind damage.

The derecho that hit Ottawa on the afternoon of May 21, 2022 cut a huge swath across southern Ontario and Quebec, with winds reaching 190 km/h, along with torrential rain and at least four localized tornadoes. By that evening, the City of Ottawa’s Emergency Operations Centre moved into “enhanced operations,” according to the report.

The storm downed trees and snapped hydro poles. More than 180,000 Hydro Ottawa users lost power, some for almost two weeks.

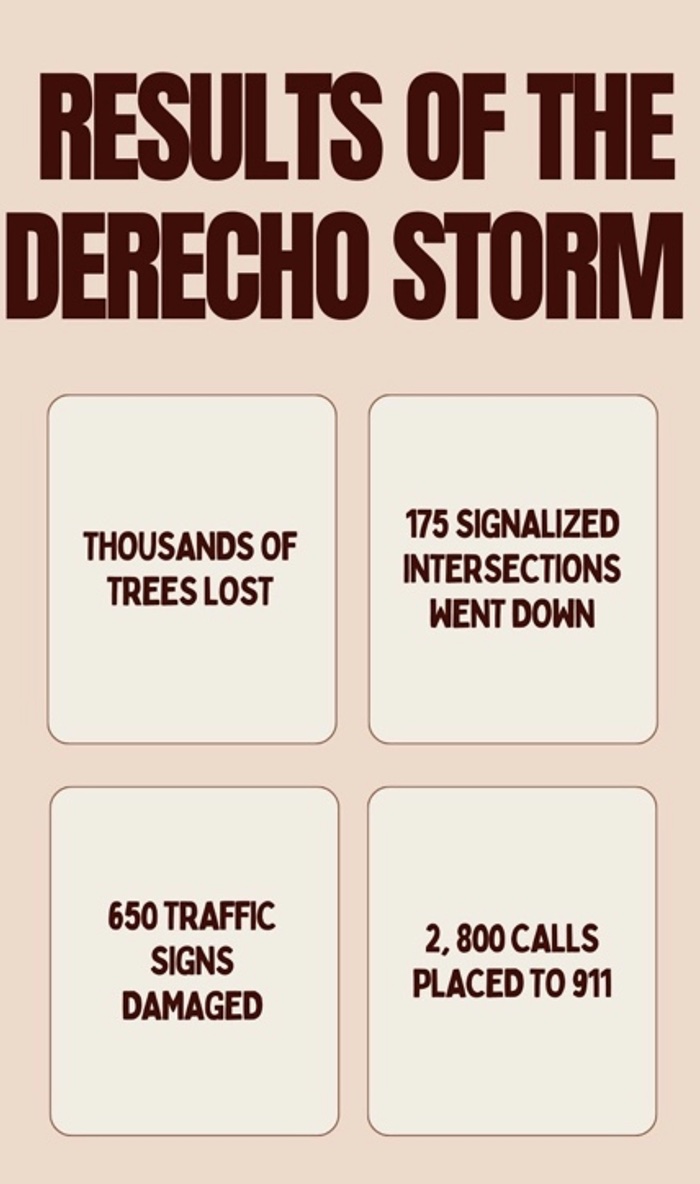

In the first 24 hours, the city’s 911 system received 2,800 calls — three times more than they would normally get in a 24-hour period at that time of year.

“Considering the size and scope of the event, the City conducted a well-coordinated response that aligned with the guidance of the Municipal Emergency Plan,” the report concluded. “The rapid and skilled response from first responders helped to save lives. The Human Needs Task Force was still supporting pandemic response and was quickly able to transition to support broader community needs associated with the City’s storm recovery efforts.”

The report also noted that “volunteer agencies were a valuable partner that provided support and subject matter expertise, where needed.”

In terms of areas of emergency response that require improvement, the report noted that “the city should continue to build greater depth in emergency response capacity such that more staff are capable of fulfilling crucial roles during situations.”

The report identified a need to “enhance public education and awareness related to emergency preparedness at both the individual and community levels.” It also highlighted the need to prioritize the development of “ formal response protocols in three key areas: 1) Food Security; 2) Wellness Visits; and 3) Volunteer Management.”

‘We’ve heard stories about people in wheelchairs being trapped on the ninth floor, in the dark with no water.’

Theresa Kavanagh, Bay Ward Councillor

The report also stated that “the city should review and update its existing agreements with non-governmental organizations, as well as enhance its public-private partnerships – both with a view to working more efficiently with external partners during emergencies.”

Finally, the report concluded that “the city should continue to seek ways to communicate effectively with the public during prolonged power outages.”

The Emergency Operations Centre was active for 17 days after the storm and was responsible for communication between the city and hydro companies, and the city and residents concerning fallen trees, emergency shelters and more.

The city’s emergency services quickly mobilized, the report concluded, adding the emergency management program is comprehensive and considers all municipal departments and three boards overseeing police, public health, and public libraries. This ensured city-wide understanding and compliance with the program’s recommendations.

Emergency services relied heavily on first responders, volunteer organizations and spontaneous volunteers to ensure safety. These three groups were found to be highly effective in providing aid to residents through debris clean up, providing meals and strengthening communication, the report stated. More than 1,000 city employees were on the frontlines assisting affected areas.

After receiving the report, members of the emergency preparedness and protective services committee thanked the work of all frontline workers and volunteers.

“I do want to thank all the residents who really stepped out and said listen, we’re going to help each other, we’re going to get through this. And you know, that’s one of the reasons why I love our city,” said Orleans West-Innes Coun. Laura Dudas.

‘I do want to thank all the residents who really stepped out and said listen, we’re going to help each other, we’re going to get through this. And you know, that’s one of the reasons why I love our city.’

— Orleans West-Innes Coun. Laura Dudas

The derecho damaged many hydro lines, leaving thousands of local residents without power and disrupting communication. People without access to data could not go to Ottawa.ca to receive updates from the city, and for those who did have access to smart devices, the prolonged time without power meant their batteries could not be sustained.

This left many residents without access to information and left councillors with reduced capacity to communicate with residents in their wards.

The city’s emergency services do not have a comprehensive list of vulnerable communities or buildings, the report found. During the derecho, assistance was spread out across the city, but planning did not account for neighbourhoods hit hardest by food insecurity or accessibility issues.

“We’ve heard stories about people in wheelchairs being trapped on the ninth floor, in the dark with no water,” said Bay Coun. Theresa Kavanagh. During the derecho, she said, an emergency centre was not set up in her ward, making it difficult for residents in that west-end area to access food and shelter.

Since the derecho, the Office of Emergency Management has been working with the city’s Accessibility Office and advocacy groups to better assist people with disabilities during a crisis.

The report said “the city’s climate resiliency group indicate(s) that Ottawa is expected to become warmer and wetter over the next several decades.” This could lead to more severe weather events. The emergency preparedness and protective services committee is expanding its risk assessment program to investigate crisis management for the top 30 potential risks Ottawa may experience.

During the derecho, thousands of trees were also lost. The “Trees in Trust” program has been established by the city’s Public Works Department to allow residents to request the replanting of trees that were lost during the storm.

The report critiqued various aspects of the City of Ottawa’s emergency response. The report also excluded analysis of the role of Hydro Ottawa and the province’s Hydro One in handling the disaster.

Hydro Ottawa has produced its own after-action report, but it’s unclear if it will be shared with the city or residents.