With Ontario students returning to school in September, a group of medical experts is advising against strict physical distancing measures that they say put strain on mental health.

Researchers from SickKids hospital in Toronto published a document on June 17 offering recommendations for schools opening in the fall, including an emphasis on hand hygiene, regular screening and lenient distancing. The report also discourages making face masks mandatory in the classroom.

“Strict physical distancing should not be emphasized to children in the school setting as it is not practical and could cause significant psychological harm,” the report stated. “Close interaction, such as playing and socializing, is central to child development and should not be discouraged.”

The report recommends hand washing tutorials to teach students proper technique, and “hygiene breaks” scheduled throughout the day.

On June 19, Ontario announced tentative plans to open schools in September after consulting health experts, including those at SickKids.

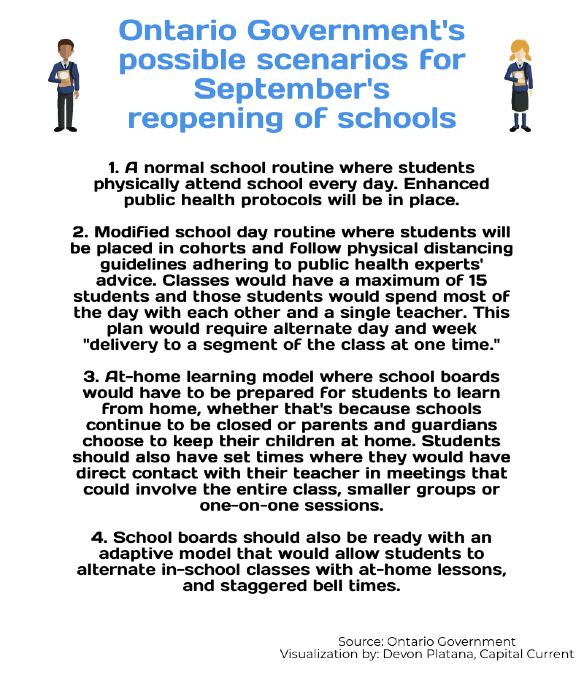

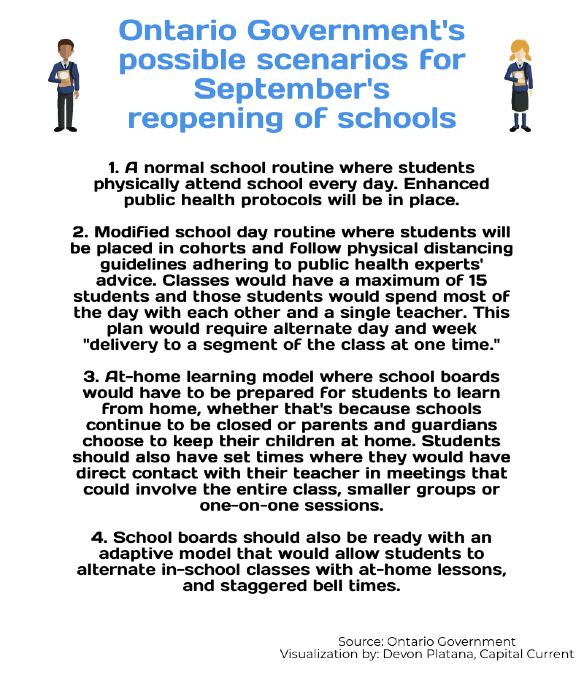

The announcement suggests different scenarios for the fall, “depending on the public health situation at that time,” including smaller class sizes and a potential blend of in-school and at-home learning.

When it comes to a possible return to the classroom, Ottawa teacher James Grant said mandatory masks would make him feel safer, despite of the report’s recommendations.

“Proper cleaning of the classrooms and bathrooms, as well as masks, would make me comfortable,” said Grant, while acknowledging that rules requiring students to wear masks would be difficult to enforce, especially for younger elementary school children.

“Younger kids could fiddle with them (masks), pull on each other’s, trade masks, take them off when they’re unsupervised in the bathroom or out of sight on the school yard,” said Grant. “Older kids who have parents who don’t believe in COVID or refuse to give it the respect it deserves could possibly rebel or be difficult about it.”

While the SickKids document explains that the risk of COVID-19 in children is “minimal,” Grant said that he is worried that schools might contribute to second-wave outbreaks if proper measures are not put in place.

“I’m not too concerned for myself as an individual, honestly,” added Grant. “I’m more worried about our entire population.”

When Quebec reopened elementary schools on a voluntary basis in May outside of Montreal, students were required to stay two metres apart and classrooms were capped at 15 students to allow for distancing.

When Quebec’s reopening was announced, some parents expressed concerns about their children sitting in classrooms for many hours with little interaction with teachers or fellow pupils, and about the heightened risk of children contracting and spreading COVID-19.

Some parents, such as Ottawa resident Daniel Pascuet, have no qualms about sending their children back to school in September. He said he feels “very comfortable” with the idea, even amidst uncertainty about what the fall might look like.

But not all parents feel as comfortable as Pascuet.

Melissa Marchant, a mother from just outside of Shawville, Que., said that she and her husband are wary of sending their seven-year-old son back to school.

“Some of my concerns involve the feelings of the government using our children as guinea pigs,” said Marchant. “They aren’t sure how this virus will mutate or what long-term side effects will this have on our children.”

When Quebec schools reopened in May, Marchant decided to keep her son at home. It’s a decision that she struggled with because her son misses his friends and teachers.

While the SickKids report cites negative impacts of school closures on students’ mental health, Marchant said that returning to a drastically different school environment might do similar damage.

“The teachers, and school staff all in masks, desks pushed apart … staggered recesses. Not being able to interact with all their friends,” she said. “I get that we’re in a changing world, but, we need to protect our most precious people: our children.”

Marchant said that she recognizes that many people may not be able to keep their kids at home, especially in households where both parents work full-time.

Whatever decision her family eventually makes, Marchant said that it will be made with her son’s best interests in mind.

“It’s a decision I struggle with daily: What is best for him?” she said. “Everything is so upside down, all I can do is go with my gut.”

[…] Source link […]

[…] Ontario government has taken a similar approach with three envisioned scenarios, the first being regular school days, the second having smaller […]

The average family works

Monday to Friday. The average salary is less than 80k a year. So both parents have to work to pay for the mortgages and rent for housing that is way too expensive to begin with. Not to mention all the other bills not regulated. Now these families will need to pay for 3 days a week for their kids in childcare-in centres were there will be a ton of children because PARENTS HAVE TO WORK. It’s got to be so nice for families where one parent stays home but that’s not the norm and not returning to school is putting millions of people in financial jeopardy. Hire more teachers. Have smaller classrooms. Figure it out. If you don’t want your child to return then you figure that out. The majority of people need school to return for financial, emotional and mental health reasons

Melissa said it all! Students MUST return to school FULL time.

The gov’t needs to continue providing financial payments. I have a right to keep my child safe