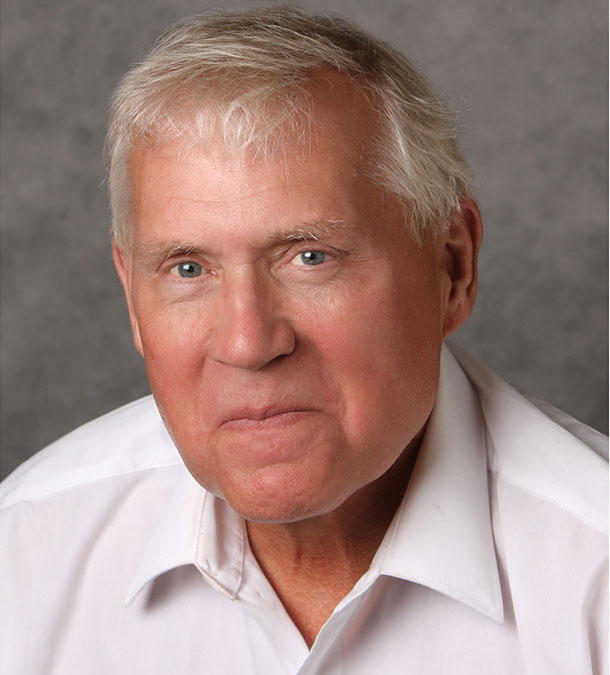

Ashton Mathias has been renting in Ottawa for a few years and recently started living with his partner. While he said he hopes to purchase a home one day, he said the odds of becoming a homeowner look particularly bleak now.

“There’s a lot of competition for housing, whether it’s a rental or even to buy a house in the first place. So No. 1 is because of the income to house price ratio. No. 2, the pace at which housing is not keeping up with the population growth,” he said.

Mathias said he saves 40 per cent of his monthly income for investments. At some point, his savings could go towards a down payment on a home, but it would take a few years to make this achievable.

“A lot of the house prices in Ottawa, I think, are very, very high and maybe overpriced,” he said.

Mathias’s father is a real estate agent, and his motto, according to Mathias, has been to look at home ownership as the one way to success and wealth.

“I kind of pushed back on that, just saying, ‘No, there [are] other ways to build wealth.’ And homeownership may have been easier for perhaps his generation but not actually for ours. So, it is a little discouraging. I think it’s still a little bit more normalized, the idea of renting for the long term, either for your lifetime or even just a longer time than they used to.”

A recent Statistics Canada report found that people born in the 1990s, whose parents are homeowners, are twice as likely to own a home in 2021 compared to those whose parents are non-homeowners. The rate of homeownership was 17.4 per cent for children of homeowners. In contrast, the rate was 8.1 per cent for children of non-homeowners.

Today, many factors determine a young person’s likelihood of purchasing a house in the future. They’re facing more difficulties in being able to afford a down payment, resulting in fewer young people thinking they will one day become homeowners.

Bank of Mom and Dad a ‘powerful force’

Ian Lee, an associate professor in the Sprott School of Business at Carleton University, said it’s statistically more likely that children of homeowners will purchase a home because the vast majority of a homeowner’s wealth goes to their children after they die.

“If their parents owned a house, then they’re going to inherit a whole bunch of money,” he said. “And if they don’t already own a house, then they can go and buy a house.”

Lee also said property prices can increase because of inflation. Or, if a person renovates, it makes their property more valuable. As a result, the homeowners’ children will inherit that extra wealth, which could allow them to buy a house.

In addition, Lee said the Bank of Mom and Dad can consist of other family members and not just solely parents. He said he has also seen parents advance their children’s inheritance, helping them afford the down payment.

“It’s not in any textbook. You won’t find this in any textbook or any official government document in Canada,” he said. “The Bank of Mom and Dad is an incredibly powerful force in Canadian society.”

Steve Pomeroy, the Senior Research Fellow for the Centre for Urban Research and Education (CURE) at Carleton University, said the Statistics Canada report is not a surprise.

“Having someone to give you that down payment obviously makes [purchasing a home] much easier, which is why we see the differential between the ownership rates for those with parents with equity versus not,” he said.

Pomeroy teaches at Carleton University and has started asking his students their expectations of being able to buy a house in the future. One of his colleagues has been asking his students the same question for more than 20 years.

Pomeroy said when he has asked the last two summers, no student thought they could buy a home. Last year, a third of the students asked said they didn’t even want to buy. Pomeroy sees this as a sign that attitudes towards ownership amongst young people are changing.

“I think it was more just the fact that the frustration, the fact that the [financial] gap was so big, they were never going to get there, and they’ve just given up on the aspiration.”

Barriers to homeownership

While children of homeowners are more likely to purchase a home, barriers still prevent young people from doing so.

Canadian regulations require a down payment of at least five per cent on homes up to a purchase price of $500,000, more for more expensive. This means a $500,000 home would require a down payment of at least $25,000, while a $750,000 home would require that payment to be $50,000. Lee said there is a bias in these rules against people who don’t have money.

“If you don’t have any money and you don’t have a down payment, you cannot buy a house,” he said. “The laws of our country discriminate against people that don’t have any money.”

Pomeroy says socioeconomic characteristics play a role in young people’s access to housing. He said if a person comes from a family with less income, that person has less opportunity.

“All of those social determinants of economic outcome would come into play based on income and the fact that rental incomes are lower,” Pomeroy said. “So you’re sort of starting off with a disadvantage.”

“Leaving aside whether your parents give you any money, just the way you were brought up, just because of the opportunities that you had, there is going to be a difference. And that would explain why those ownership parents have a higher percentage to some extent, alongside the fact that they’re giving some money.”

Renting long term

There are alternatives to buying. Some countries, notably Switzerland and Germany, have far lower rates of home ownership than Canada. In these countries, and others, people rent instead.

Pomeroy says from a labour market perspective, there are trade-offs between renting and buying.

“I think we are moving to the point now where people are scratching their heads and saying, ‘Well, do I really need all the stress of trying to own?’”

Pomeroy said there’s been a dramatic increase in people choosing to rent because renting is more affordable than buying. But he said once a person starts spending a massive amount each month on rent to “pay for someone else’s mortgage,” that can change the calculus for some people.

“There’s nothing wrong with renting. It’s very much part of our culture [and] other cultures,” he said. “Renting is perfectly normal, and a lot of people do it.”

Pomeroy said the policy bias towards ownership provides assistance, grants and non-taxation of capital gains. He said these things encourage people to purchase a home because they will acquire an asset once they own a home.

“When they retire, they’ll be able to use that asset to help them with their retirement income. So there’s some inherent logic to that. But it is a different sort of circumstance.”

As for Mathias, he and his partner will be in Ottawa for the foreseeable future. He said they will have to accept the reality at some point that they need to start saving up for a down payment and start looking for a house.

“I think [that] is multiple years away, keeping in mind there is the option, of course, just to rent for the rest of our lives. But I think we have to see, based on what the interest rates are and what the overall house price would be versus … what makes more financial sense.”