Flu clinics in Ottawa have opened up this month as part of the Ottawa Public Health influenza prevention strategy, one month later than usual. As of Nov. 9, 10 cases of the influenza A strain and three cases of the B strain had been lab-confirmed since Sept. 1, according to Ottawa Public Health. The agency also reported one influenza-related death. Reports earlier this year suggested there would be a delay in vaccine distribution and the first round of vaccines were delivered in late September in Ontario and allocated to high risk groups such as seniors.

Although the late vaccine distribution may cause longer wait times at clinics, one group that probably will not wait in line is what the World Health Organization (WHO) calls “vaccine hesitant” individuals. Vaccine hesitancy was listed as one of the WHO’s top 10 threats to global health in 2019.

Vaccine hesitancy

WHO defines vaccine hesitancy as the reluctance or outright refusal by people to be vaccinated despite availability of vaccination services. In the organization’s words, “the reasons why people choose not to vaccinate are complex; a vaccine advisory group to WHO identified complacency, inconvenience in accessing vaccines and lack of confidence are key reasons underlying hesitancy.”

Vaccine hesitancy is making news in Ontario as the non-profit organization Vaccine Choice Canada fights Ontario’s child vaccination laws. The current law requires parents to have their children vaccinated against a specific list of diseases to be eligible to attend school, unless they have been granted a medical or religious exemption.

Toronto’s Medical Officer of Health, Dr. Eileen de Villa, said in a media release on Oct. 7, that there has been a steady growth of non-medical exemptions in Toronto over the last few years. Rising from 0.8 per cent in 2016 to 1.7 per cent in 2019.

In Ottawa, according to Marie-Claude Turcotte, program manager of the Immunization Unit at Ottawa Public Health, “we’re always around the two per cent mark, which tells us it’s pretty stable, the number of parents who are asking for a non-medical exemption [for their children].”

Although influenza vaccines are not mandatory in Ontario, Vaccine Choice Canada (VCC) has posted more than 40 articles pertaining to flu vaccines on its website.

When asked if the organization had found any negative consequences associated with flu vaccines, Gisele Baribeau, director of Vaccine Choice Canada, said that they have consulted many studies that question how effective these vaccines are, as well as the risks they pose.

Baribeau said that any medical intervention has risk. In her words, “our concern is that Canadians are not fully informed of risks versus benefits when it involves vaccination.” She said because the efficacy rates of the influenza vaccine tend to be low, the risk of taking it is even more relevant to Canadians.

Baribeau also described how, in October, VCC launched a charter challenge against the “compulsory nature of Ontario vaccine regulations.” This is part of the organization’s mandate, which she said is to advocate for informed consent and voluntary vaccination decisions. As Baribeau explained, “where there is a need with existing or new legislation in a province, we will be there to protect the rights of Canadians.”

A change of heart

Arnprior resident Tara Hills has been on both sides of this issue. From 2009 to 2015, Hills chose not to vaccinate her seven children. She said some of the major factors that contributed to her vaccine hesitancy were the anti-vaccination sentiment she heard from other moms and from social media, in addition to her own skepticism of authority.

After one of her friends, a health advocate, asked her to look more closely at her sources, Hills began vaccinating her children again in 2015.

“Within two days I knew that the anti-vax contingent didn’t have this wealth of well-supported, well-documented, peer-reviewed studies that I expected were there,” said Hills.

Hills, who now has nine children with a 10th on the way, said she continues to share her experience because she worries vaccine hesitation could become more popular, particularly among parents.

“It’s totally okay to have questions and feel hesitant, but I would urge them to use that and go forward to find answers to their questions by checking the resources carefully,” said Hills. “But don’t just stay hesitant, get answers and check your sources.”

Hills said she does not support mandatory vaccinations. In her words, “this is in large part a communication issue and would be better addressed with improved communication, not the threat of government force or punishment.

“Our government is better than that and should be willing to take responsibility and do the hard work to maintain civil freedoms while addressing complex issues,” she said.

Locally, Ottawa Public Health is already working to bridge this alleged communication gap. Turcotte said, “now that it’s flu immunization season, we do a lot of promotion about flu vaccines on social media. We work with the schools to promote vaccines, we work with different partners to get the word out there, and we also work one-on-one with parents when they come in to do an information session, if they want to put in an exemption.”

Flu vaccine effectiveness

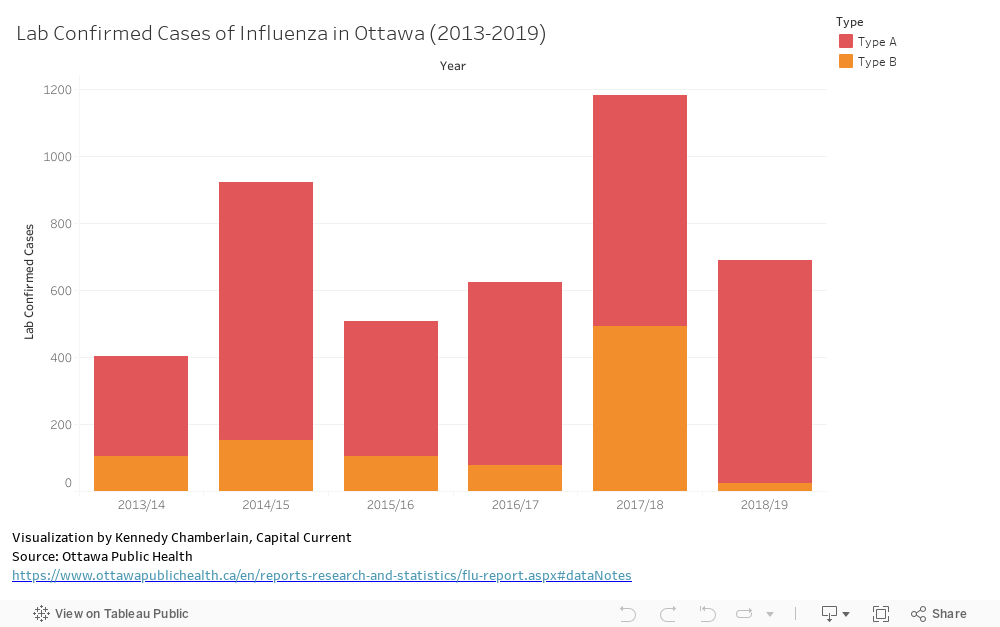

In addition to vaccine hesitancy, the effectiveness of flu vaccines is contentious, especially after the low efficacy rates during the 2017/18 flu season.

“It can vary anywhere from 50 to 90 per cent,” said Dr. Ramachandran Nair, vice-dean in the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Ottawa. “For example, when we are developing a vaccine it is based on what we know currently, and by the time the vaccine is created and administered, the virus might have mutated. Therefore, it may not be as efficacious.”

Dr. Nair said he believes that in the middle age group, compulsory flu vaccinations may not be needed, but for those in groups at greater risk like young children and the elderly, it should be essential. He also said that some within the medical community are worried about vaccine reluctance because it disrupts the concept of herd immunity.

According to Dr. Nair, herd immunity can be achieved when a large percentage of the population is immunized, roughly 80 to 90 per cent, reducing the chance of an epidemic. Growing non-medical exemptions of vaccines has the potential to disturb the equilibrium of herd immunity in Canada.

“People opting out of vaccination is completely against the principles of public health. Unfortunately, there have been a lot of arguments about one particular study about autism related to vaccination, but that study itself has been debunked. There is really no need for anyone to fear the flu vaccine as being a cause for subsequent diseases. The medical community is in fact quite worried about vaccine reluctance,” Dr. Nair said.

Dr. Usha Krishnan, specialist in internal medicine at the Royal Victoria Health Centre in Barrie echoed Dr. Nair’s concern.

“[The] medical fraternity is very upset about vaccine hesitancy and anti-vaccine drive for childhood illnesses such as chicken pox, smallpox, measles, rubella and things like that which have been eradicated because of active vaccination. Now we are seeing a surge because the population is naïve,” Dr. Krishnan said.

Dr. Krishnan said he worries that if these diseases were to come back en masse, the viruses may mutate over time, making current vaccination practices ineffective.

In her statement to the press, Dr. de Villa claimed that in Toronto, an evidence-based conversation is part of the solution to this debate.

“We need to start with this conversation now, so that we don’t find ourselves in a situation with several outbreaks that cause severe illness in children and contribute to added strain and ultimately cost to our health-care system as a whole.”