Growing up, my little brother Jaden always stood out from his peers. He hated loud noises and Victoria Day with a passion, loved planes and was more empathetic and sensitive than anyone I know. He was as passionate about his Q400 model planes as he was caring for our infant cousins.

No one in my family was surprised when he accepted his offer to attend Ontario Tech University for mechatronics — a combination of mechanical and electrical engineering and robotics.

Though Jaden showed many of the early signs of autism, he was not diagnosed until he was 13 — much later than the typical detection age of four years old. This may be because of our family doctor’s ignorance or the stigma around the diagnosis. Or, it may be because he was a young boy of colour.

People of colour often go unnoticed or are overlooked for a variety of reasons in the health-care system. Black women in the U.S. are three times more likely to die during childbirth than white women, and people of colour are less likely to receive the same care as their white counterparts.

The same holds true for autism diagnoses. Although one per cent of the population has autism — almost the same number of people with red hair — people of colour are often less likely to be screened for autism and tend to receive a lower standard of care after the diagnosis.

Autism affects people in different ways and can include barriers with socialization and sensory issues. People with autism are on a spectrum because people experience the disorder in a variety of ways.

Although one per cent of the population has autism — almost the same number of people with naturally red hair — people of colour are often less likely to be screened for autism and tend to receive a lower standard of care after the diagnosis.

But many advocates — and my brother — say autism is exceptional. Many people with autism have “special interests,” which are topics or areas of study to which they are able to give a higher than usual degree of focus and time. My brother’s enthusiasms have fluctuated between planets, airplanes, drones, blockchain and being the next Elon Musk at various points in his life.

Unfortunately, many people with autism also face social stigma. And, people of colour with autism often face discrimination in society and in health care specifically.

Understanding what disparities exist in the quality of care for people of colour can help not only minority and racialized groups receive better care in autism diagnosis and treatment, but can also help the medical field in general.

“Identifying and implementing effective strategies to eliminate racial inequities in health status and medical care should be made a national priority,” states one U.S. study published in 2000 in the journal Health Care Financing Review.

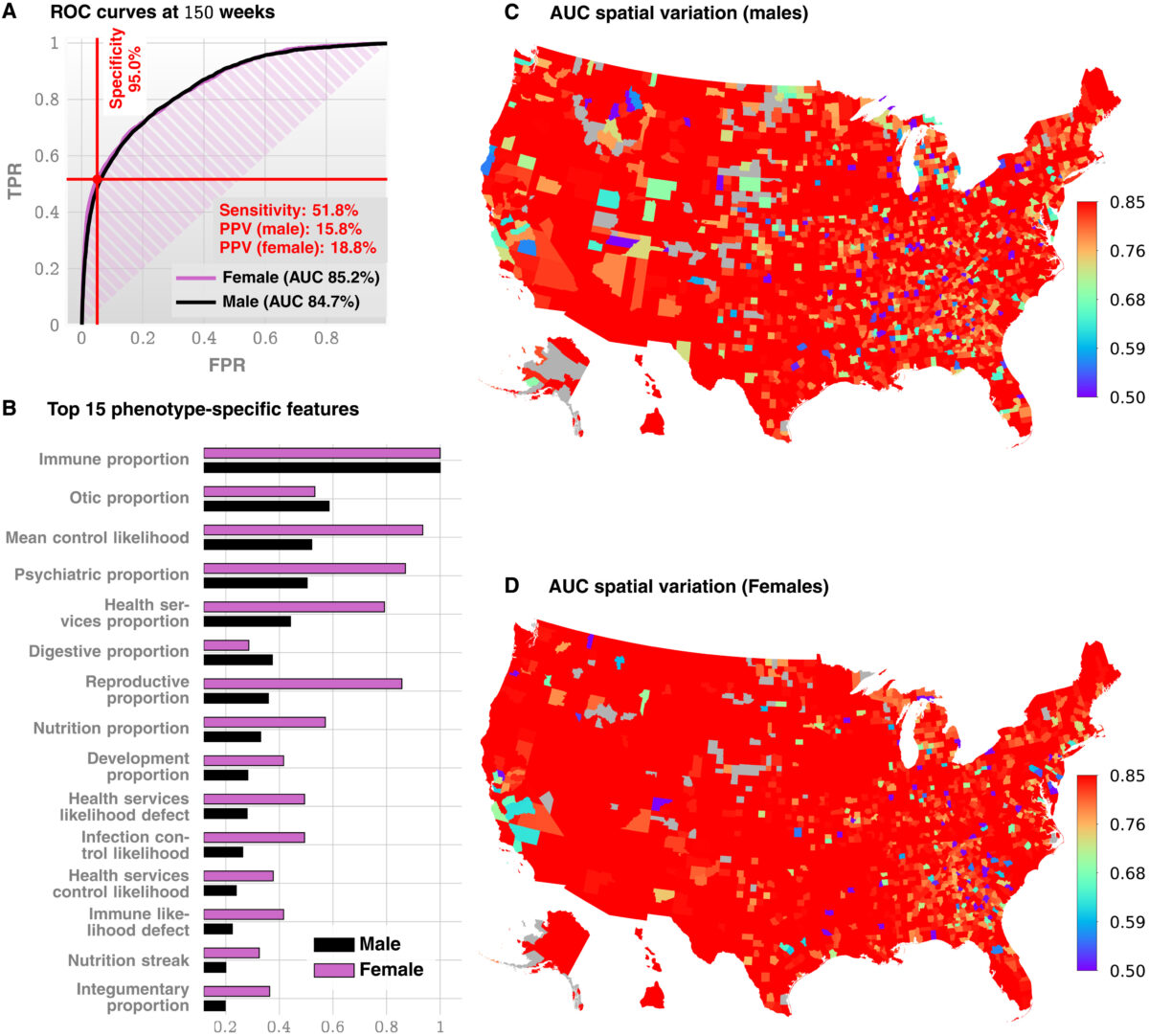

Another study, published by University of Chicago researchers in October in the journal Science Advances, proposed a new Artificial Intelligence tool to help eliminate bias when diagnosing autism.

In typical autism diagnoses, parents of children suspected of having autism are given questionnaires based on the medical provider’s professional opinion, according to Dr. Ishanu Chattopadhyay, the lead researcher in the study, which tested these new AI diagnostic tools.

“Most of the tests that are done for autism currently in screening tools are not really that objective,” he stated.

The traditional diagnostic practice creates long queues for autism diagnoses and can ignore underserved populations, including women and people of colour.

“If the children are not diagnosed before they start school, then the effectiveness of interventions is dramatically reduced,” Chattopadhyay said.

Today, my brother is a thriving and well-rounded 18-year-old with professional experience and interests beyond his years. He still deals with some anxiety and the general barriers of autism, as well as being a person of colour, but he’s thoroughly proud of who he is.

I hope that other children of colour exhibiting autistic traits would not be overlooked as he was all those years ago. And, I hope that the medical field in general begins to treat people of colour the same as our white counterparts.