The Ottawa People’s Commission has heard more traumatic first-person accounts delivered by residents who were personally affected by the Freedom Convoy occupation earlier this year.

Witnessesgot five minutes to recount their experiences with the trucker blockade that shut down central Ottawa in January and February over vaccine mandates and other issues.

The grassroots inquiry into the impact of the convoy occupation on downtown residents, has been holding hearings throughout the fall and is happening at the same time as the Public Order Emergency Commission is probing the federal government’s controversial invoking of the Emergencies Act to end the trucker blockade.

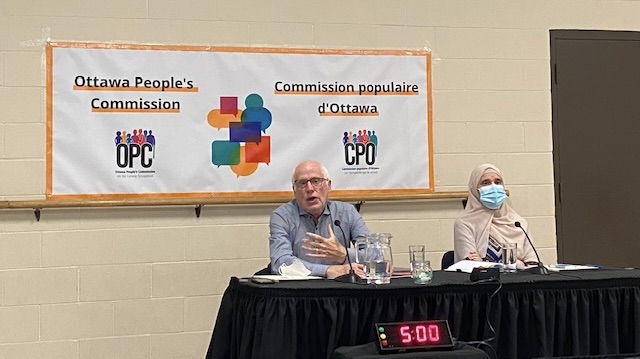

Two of the OPC’s four commissioners — human rights lawyer Alex Neve and author and human rights activist Monia Mazigh — led the Nov. 5 hearing held at the Jack Purcell Community Centre in Centretown.

The witnesses, residents of the downtown core or workers in the central part of the city, said the convoy occupation was unlike any protest they had ever witnessed.

“I’ve seen how protests often have many passionate supporters voicing causes vigorously, mostly polite. And they leave again, to live out their convictions at home. Most of us understand that this is what life in a capital city is like, especially downtown. The Freedom Convoy was a very different, disorderly, divisive experience for so many,” said Rev. Jim Pot, of Knox Presbyterian Church.

One resident who identified herself as Dawn, echoed this opinion.

“The number of bylaws that were broken and the level of fear, discomfort and intimidation and inconvenience it imposed on both myself and residents of this downtown core — I’d never seen this before,” she said. “It reminded me of being bullied as a child.”

Throughout the hearing, witnesses described the inconvenience they endured and the harassment and torment caused by the occupation.

Dawn, who described herself as a queer, disabled downtown resident, said the incessant honking by convoy trucks in the early days of the occupation exacerbated her tinnitus and caused her severe headaches.

“The use of noise — now that is a tactic of psychological warfare. That’s what the Americans used in Vietnam and there are many other instances where it has been used,” she said.

Truckers were “honking horns for 12 hours or more — even once there was a court order issued against the honking,” she said.

The convoy’s presence also prevented Dawn from seeking dental treatment that she said she desperately needed.

“The convoy blocked access to essential medical appointments. Trucks parked along Queen Street forced my dentist to close office at the beginnings of a dental abscess,” she said.

“The blockade meant the preventative treatment I needed was not available.”

Pot said that, during the occupation, he witnessed incidents of disrespect directed by convoy supporters towards his church, volunteers, guests attending Knox’s charity food service — and even himself.

“I also recall the following: Protesters urinating against our church walls, volunteers mocked by protesters for wearing masks, our dinner guests in line harassed to take off their masks,” he said.

“During my walk to Knox to assist our volunteers, I was brutally threatened by three protesters,” Pot added. “I’ll never forget when the loudest person’s unmasked face shouted directly into mine about four inches away, ‘Get the hell out of my face.’ Ironic.”

The convoy disrupted church services, one of which was a weekly meal program for those in need.

“One of the Saturdays of our meal program, a group of protesters became visibly angered on seeing our church sign that stated ‘Online worship only.’ One of them pointed a fist towards me, shouting, ‘You should obey God, rather than ‘effing Trudeau’. Ironic, again, how these folks were the very reason we had delayed in-person gatherings,” he said.

‘The number of bylaws that were broken and the level of fear, discomfort and intimidation and inconvenience it imposed on both myself and residents of this downtown core — I’d never seen this before. It reminded me of being bullied as a child.’

— Dawn, a downtown Ottawa resident

Dawn said she also experienced harassment at the hands of convoy protesters, all because she wore a mask to protect her 85-year-old mother at home.

A convoy supporter “followed me, screamed and yelled at me for wearing a mask, moved close up to my face and then they started to video tape my angry reaction to harassment,” she said. “They taunted me and they told me they would post my reaction on Facebook and dox me.”

Many months after the occupation, Dawn says she still suffers from the effects of the trauma she experienced.

“Frankly, writing it (her experience) down was re-traumatizing. … I still jump when I hear a loud noise or a horn,” she said, referring to the written statement she read to the commissioners.

Despite complaints and attacks on downtown residents and their property, witnesses said the police were, at best, disengaged and unhelpful.

Andrea Harden, who described herself as an experienced campaigner and participant in social movements and protests, said that police were ineffective in responding to the unlawful occupation.

“The police kind of stood back, didn’t really engage a lot with what was happening,” she said.

Pot said police he spoke to claimed they were unable to assist in a more active way.

“Their constant refrain was that they didn’t have adequate resources and they could only respond in accordance with directives from higher up,” he said.

Dawn also expressed her frustration with the lack of police action in the face of obvious bylaw violations.

“We had no or little help from the police or the city. I complained about the noise to the City of Ottawa bylaw (department). … I made calls, I filed online reports about the noise infractions — nothing,” she said.

‘I also recall the following: Protesters urinating against our church walls, volunteers mocked by protesters for wearing masks, our dinner guests in line harassed to take off their masks.’

— Rev. Jim Pot, minister at Knox Presbyterian Church, recalling incidents during Freedom Convoy

Harden, whose brother is Ottawa Centre NDP MPP Joel Harden, said the leeway the police gave to convoy protesters was unlike anything she had experienced throughout her involvement in peaceful protests.

“I remember once organizing a rally on Parliament Hill and bringing some props and going through all of the proper protocols and was kicked off Parliament Hill because I had a stick — and that was considered a potential weapon,” she said.

“I’ve been threatened with arrest for having a group of folks on Wellington Street talking about climate justice simply by not crossing when the light was red,” she continued.

“So seeing a bunch of trucks in our downtown and witnessing police watch this happen on the sidelines, was disturbing to say the least.”

Harden said that there were instances where the police not only disengaged from the conflict, but added to it.

At one point, officers were attempting to get a truck moved to a different location. Harden’s partner yelled “jerry can” to alert the officers that there was a gas container in the vehicle. According to Harden, this caused one of the police officers to get angry, and start yelling in her partner’s face.

“So I ran towards my partner … and basically tried to intervene and say let’s calm things down … and the police officer (put) his hand on me and pushed me aside quite hard,” she said.

There were no charges pursued against her partner or the police, even after the conflict escalated briefly when her partner pushed the officer in response and was then dragged aside by three other officers.

Harden also described how she and a group of other community members successfully prevented trucks from getting downtown and were approached by the police. The so-called “Battle of Billings Bridge” saw Harden lead fellow citizens in stopping a line of convoy vehicles that were intending to reinforce the downtown occupation.

“There was a moment when a pickup truck was coming forward and it was very clear to me they were inching forward closer and closer to this group of people and I just began becoming really worried that they were going to push through this crowd of people. And I suppose I felt a sense of responsibility … so I threw my back against the pickup truck,” she said.

“We stopped them. We did not allow them forward. About 10 minutes later the cops arrived … The first thing that came out of that police officer’s mouth was: ‘You understand that you could be arrested for this?’ ” she said.

Harden said that the way convoy protesters were handled was vastly different than how racialized groups she has organized with in the past had been treated.

“Compared to the treatment of folks who have organized here in the past, particularly indigenous, BIPOC folks, it was just completely different. Utterly different.”

Despite the difficulty of re-telling her traumatic experiences with the convoy, Dawn said she was there at the hearing to help prevent something like this repeating in the future.

“The reason why I’m here is because I don’t want this to happen again,” she said.

“The last thing I want to say is a quote from (Canada’s ambassador to the United Nations) Bob Rae: ‘A truck is not a speech. A horn is not a voice. An occupation is not a protest. A blockade is not a freedom, it blocks the liberty of all. A demand to overthrow a government is not dialogue. The expression of hatred is not a difference of opinion. A lie is not the truth.’ “