As Canadian children head back to school this fall, their parents continue to hear politicians extolling the virtues of $10-a-day childcare.

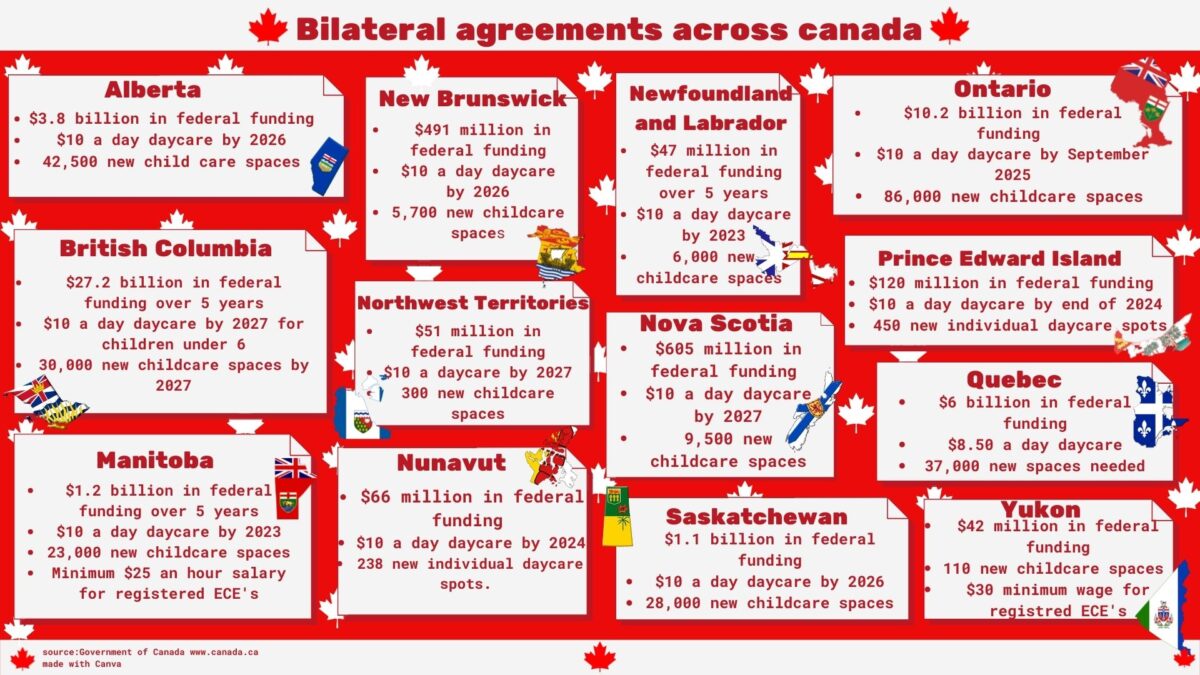

The $30-billion plan, introduced in the 2021 federal budget, aims to make $10-a-day childcare available to all, including parents who live in rural areas, work unusual hours or have children with special needs.

But while every province and territory has signed on, an increasingly critical worker shortage threatens to derail the program.

StatsCan reports that Canada’s childcare workforce shrank by 21 per cent during the pandemic. According to Jim Stanford of the Centre for Future Work, that shortfall and the anticipated expansion of demand under $10-a-day childcare means an additional 200,000 childcare workers will be needed over the next decade, almost double the current number.

Rachel Vickerson, executive director of the Association of Early Childhood Educators of Ontario, says better compensation and working conditions are key to solving the problem. Vickerson’s association wants wage floors of $30 per hour for registered ECEs who have completed requisite post-secondary training and $25 per hour for other childcare staff.

While the modest demand would result in top earners receiving just a fraction of what schoolteachers earn, the Ontario government would only commit to a guarantee of $18 per hour, followed by an increase of $1 per hour annually — but only for registered ECEs.

“The low wages are intrinsically connected to the fact that it’s a feminized and care-based profession and that that’s not valued in our economy right now,” says Vickerson, referring to the fact that, according to StatsCan, 96 per cent of childcare workers are female. “We think of care-work as being work that women are intrinsically able to do, that it comes naturally and therefore it doesn’t need to be compensated well,” Vickerson explains. “ECEs love this work, but just because they love it, doesn’t mean they don’t deserve to get paid for it.”

Bernice Nyembwa, an ECE in Toronto, says that love for the work and the children often causes ECEs to spend a portion of the little money they do earn on supplies. “The best part of the job is interacting with the kids,” she says. “We aren’t provided with materials. What are we going to do? We go buy the materials so the kids can have those experiences.”

Compensation is not the only issue plaguing ECEs. With increasing labour shortages, those remaining are forced to pick up the often overwhelming slack. Added to that are split shifts for those working with school-aged children.

“They’re working a few hours in the morning,” Vickerson explains, “then they’re off for a while and then they’re back after school. So, they’re working kind of a 40-hour week, but they’re only getting paid for 25 or 30 hours. It’s a really challenging schedule.”

The politicians extolling the virtues of $10-a-day childcare have reason to do so. Stanford’s research demonstrates significant societal benefits resulting from high-quality care for young children. As with the expansion of any sector, the additional jobs will have both direct and indirect economic benefits.

‘They’re working a few hours in the morning, then they’re off for a while and then they’re back after school. So, they’re working kind of a 40-hour week, but they’re only getting paid for 25 or 30 hours. It’s a really challenging schedule.”

— Rachel Vickerson, executive director, Association of Early Childhood Educators of Ontario

Stanford also calculates that the productivity mothers will be able to contribute once they are able to access childcare will add up to an additional $63 billion to $107 billion GDP. But perhaps the most significant benefits are to children.

Stanford indicates that people who receive high-quality childcare in their formative years are physically and emotionally healthier, happier, more productive, better educated, have fewer conflicts with the law and have better employment opportunities.

According to Stanford, high-quality childcare will literally pay for itself. For Nyembwa, there is another feature that, while lacking a quantifiable return, is nevertheless the most important benefit of all. “High quality childcare,” she says, “makes kids feel like they belong.”