As the new federal Liberal housing minister, Ahmed Hussen, is sworn in, he will be in charge of a key platform promise for the re-elected Liberal government to address the housing needs of Canadians by committing $1 billion to see more rent-to-own housing opportunities.

But critics say it may not be enough to make housing more affordable for residents of Ottawa and other parts of the country.

Carolyn Whitzman, a housing and social policy consultant and an adjunct professor at the University of Ottawa, thinks the Liberal plan is not big enough to tackle the affordability gap facing many Canadians.

“What it might do is have a few little trial projects that will help … 3,000, 2,000 households across the country,” she said.

The Liberal plan would allow tenants to buy the home they rent. Their aim is for renters to be able to pay less than market rate so they can save for a down payment on a property. Landlords would have to commit to ownership in under five years.

Whitzman explained that unless the government poured hundreds of billions into the program, it would not have a significant effect on affordability of home-ownership for the vast majority of Canadians. The small-scale housing initiatives that the federal government seems to prefer are “just nibbling at the edge of the huge problem,” Whitzman says.

A report by the City of Ottawa shows nearly 40 per cent of renters spend more than a third of their income on housing. The Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation defines affordability as spending less than 30 per cent of income on one’s home.

In the housing crisis in Canada, Whitzman said, there are two issues that stand out.

“One of them is unaffordable home-ownership, and that one is not going to be solved quickly or easily. The second is making renting less horrible for people.”

One issue that can make renting an undesirable housing option for Ottawa residents is how units that were first occupied after 2018 are not subject to Ontario’s rent control rules. Kaite Burkholder Harris, the executive director of the Alliance to End Homelessness Ottawa, says that this gives landlords have the freedom to increase rent as much as they want when a lease is renewed, “which is really scary when you think about how many people that might throw out onto the street.”

Whitzman said that unless you have wealthy parents, buying your own home will stay unaffordable for the foreseeable future. Measures such as a capital gains tax on all real estate sales, or an impactful wealth tax on homes could lower market prices enough for the next generation of adults to afford their own homes. It is unlikely any of this would be part of a future housing plan, Whitzman says. She explained that these initiatives would hurt anyone using their home’s value as a retirement plan.

Politically dangerous

“That’s why the federal government would find it politically disastrous to address the issues that have raised home prices in relation to income, by say, two or three times since the 1980s.”

“I’d like to say that there’s an easy solution to the absence of home ownership possibilities for people in their 20s and 30s. I have to say that the rent-to-own scheme isn’t it.”

The government’s other option to address the housing crisis, Whitzman said, is to make renting more stable and affordable by investing in non-profit housing on a large scale, which Canada has done before. “Non-profit housing was about 10 per cent of housing being created in the ’70s. Now it’s less than one per cent.”

Non-profit housing needs to be an essential part of an affordability strategy, according to Burkholder Harris. She said that even the rent subsidies that some low-income Canadians receive can fail to make private housing affordable.

“What we’ve seen in some communities is that landlords know the money is out there, so they increase the prices,” said Burkholder Harris. She said that this makes rent subsides less effective because they cover a smaller portion of rent than intended.

Burkholder Harris thinks that leaving housing up to market forces can fail to provide the best outcome for people.

“We assume the economy will support people, whereas I think it’s often in reverse.”

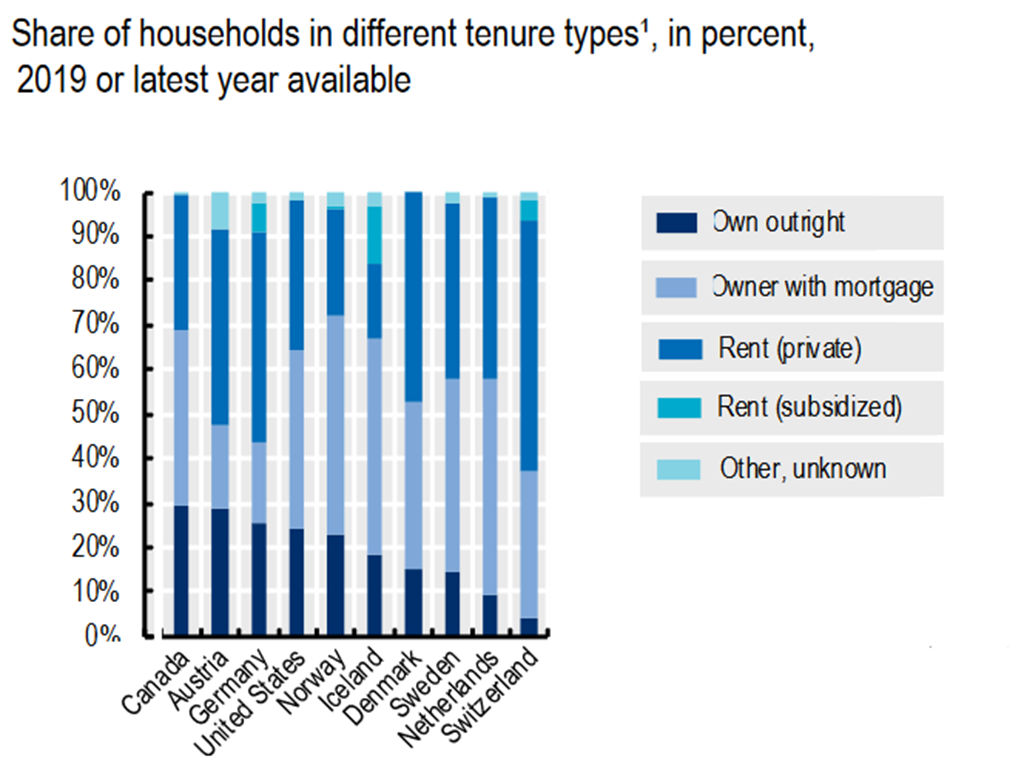

Looking at housing in other countries can give us an idea of what Ottawa might be like if more residents lived in rental units. In Switzerland, Germany and Austria, for example, where current homeownership rates sit at less than 50 per cent (compared to Ottawa’s rate of 67 per cent), people can enter into long-term leases that make renting a stable option.

“So maybe what the federal government needs to do is bite the bullet and be honest and say ‘we need a lot more rental housing in order to have affordable rental housing,’” said Whitzman. “The real question is how is Canada going to move towards that?”