The four years between elections is time enough for the resources, technology and tactics available to both the media and the political parties to change significantly. That alters the relationship between them in sometimes unpredictable ways and affects the coverage we rely on to make our decisions as citizens.

Most obviously, traditional media organizations, with the exception of the CBC, are operating with smaller newsrooms and budgets. And new technology, mostly internet-based, has changed the way the parties and an increasing array of political interlopers engage in the campaign.

Here are the four big things I will be looking for in media coverage.

Wheels up

Ever since John Diefenbaker boarded a coast-to-coast train to campaign for the Progressive Conservatives, the national leader’s tour has been the most important vehicle for the parties to convey their platforms and messages. It is the centrepiece of media election coverage.

For many decades, the parties have leased aircraft for the leaders to criss-cross the country and in recent years have charged media outlets between $50,000 and $70,000 for each journalist who comes along for the entire ride. This arrangement made it easier for the leaders to meet their exhaustive campaign schedules and made it logistically possible for reporters to follow them as they did. But, crucially, the funds contributed by the media also made the costs of leasing the large aircraft financially viable for the parties.

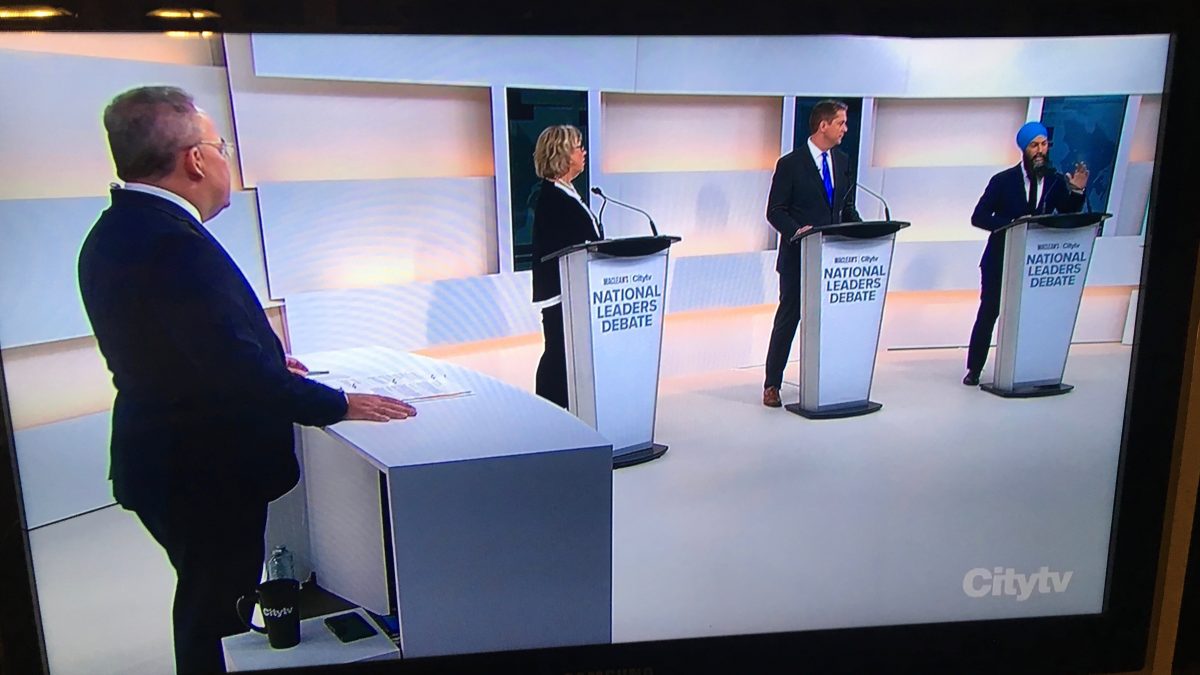

Straitened media budgets mean that fewer and fewer media organizations, including the big hitters like the Globe and Mail, are willing to spend the money to staff all the planes from beginning to end. In August, the Conservatives announced that they were dropping the cost of a seat with Andrew Scheer to a New! Low! Price! of $11,500, presumably to get more reporters aboard. This created a ludicrous contrast with the $55,000 the cash-poor NDP was charging to follow Jagmeet Singh. (The Liberals have priced the Trudeau tour at $27,000.)

I expect both the parties and the media to be shifting and adapting to this financial circumstance throughout the campaign, and there will be experimentation on both sides. But the smaller parties and perhaps even the Liberals and Conservatives will likely have to run more hub-and-spoke tours, based in major media centres such as Toronto, Montreal and Vancouver, allowing locally based media to cover them more frugally. More of the coverage we get as news consumers potentially will be written by local reporters rather than members of the Parliamentary Press Gallery. This may mean a broader range of issues gets covered, but with less continuity and less institutional memory. On the other hand, it may free political reporters from the daily grind to produce deeper stories on issues and trends.

Bots, trolls and statesmen

If Canadian politics was once a bit slow to fully embrace the world of Twitter, Facebook and Instagram, that day is over. These are now among the most important forums in which parties engage with their own partisans, with the media and with voters.

But unlike a political rally, a leaders’ debate or the door-to-door canvass, social media provides a relatively uncontrolled space, awash with partisanship, bad faith and even malevolence. The Russians, of course, have used social media to intervene in American and European elections with false or misleading content, and a recent report from an agency set up by the G7 said that supporters of the United Conservative Party had used similar tactics in the recent Alberta election.

All the major media organizations will be alert to what is happening on social media. Max Bernier has already paid a price for his decision to use Twitter to take a whack at the mental health of the teenage environmental activist Greta Thunberg. But every time the mainstream media reports on what it finds in the social media cesspool, it runs the risk of amplifying the false or misleading information there, as may have happened when Andrew Scheer decided to promote a spurious story about a convicted child murderer from Britain possibly coming to Canada.

The stealth campaign

Social media provides at least a semipublic space that the media can monitor and report on. That is not the case with many of the other campaign techniques enabled by modern computing and the internet. Parties today are constantly harvesting information about individual voters, just as private sector companies do with their customers, to predict behaviour and microtarget voters with selective messages aimed specifically at particular groups.

This targeted messaging may be through social media advertising, email or phone, or even at the doorstep. But it is inherently difficult for the media to monitor in real time at anything like its true scale of significance. The technical tools don’t yet exist, and social media companies such as Facebook have sometimes actively worked to frustrate media efforts. Needless to say, perhaps, the parties don’t help either.

In general, what the media learns about such activities comes well after the fact, so it is not possible for voters to assess the information before they vote. This was the case with Cambridge Analytica’s role in promoting Donald Trump’s candidacy in 2016.

Polls

Recent election campaigns have been awash in horse-race polling, which is cheap for polling firms to produce and easy copy for news organizations. (I wrote about this at length recently for Policy Options.) The focus on polls has encouraged a form of journalism that privileges stories about anything that seems like it has the potential to move the polls. I will be watching for the degree to which journalists allow the narrative created by the polls to determine their coverage.

Meanwhile, the sheer number of polls has led to the rise of aggregators such as the CBC’s Poll Tracker and 338Canada at Maclean’s. Paradoxically, the aggregators have undermined the ability of individual polling firms, who do the polling in part to build their reputations, to get the publicity they crave. Some firms have responded to this conundrum by undertaking deeper, more interesting work on the horse race that goes beyond what the aggregators can offer, such as the look at seat clusters by Innovative Research Group and the more detailed political tracking done by Abacus Data. It would be nice if some firms would also dive deeper on issues and attitudes — and not just from the perspective of how they might affect voting intentions. I am not holding my breath.

Of course, not everything has changed. Despite all the technological advancements and the rise of social media, voters still get most of their information about the election through traditional television, radio and newspaper outlets and the internet sites of these outlets. And the 40 days of an election campaign remains the most intense, exhausting, exciting and challenging phase of a political reporter’s career. Just as politicians reveal themselves in the artificial intensity of the campaign, stumbling or brilliantly innovating in unexpected ways, there will be reporters and editors who fail spectacularly and others who suddenly emerge from the herd. It is going to be fascinating to watch.

Paul Adams is an associate professor of journalism in the Carleton School of Journalism and Communication. He is a veteran of CBC, the Globe and Mail and EKOS Research.

This article is reprinted with thanks and first appeared on September 12 in Policy Options, the digital magazine of the Institute for Research on Public Policy (IRPP).