Shelley Ann Morris had her eyes tightly shut. On a crowded train from Rideau station to Tunney’s Pasture, and clutching a white cane, Morris was testing how easy it was for a person of low vision, such as herself, to use light rail transit. She said she had not had much input into the new transit system’s design.

The opening of Ottawa’s Confederation Line in mid-September produced mixed reactions from people with disabilities. Some advocacy groups felt the Rideau Transit Group (RTG), which built the line, should have consulted more with them.

Morris, an administrator at the Canadian Council of the Blind, didn’t meet with RTG until several days before the line’s opening, when it held an accessibility walkthrough. OC Transpo invited several groups representing people with disabilities to take a sneak peek inside three of the new stations and provide feedback.

While Morris’s experience on the tour was mostly positive, she said that earlier meetings could have reduced the issues that needed to be addressed.

“It’s a mainstay. You have to do it. Because if you try to retrofit things later, it’s harder and more expensive and more time-consuming,” said Morris. “We’ve seen instances where they think they know what people with disabilities need, but they’ve got it wrong.”

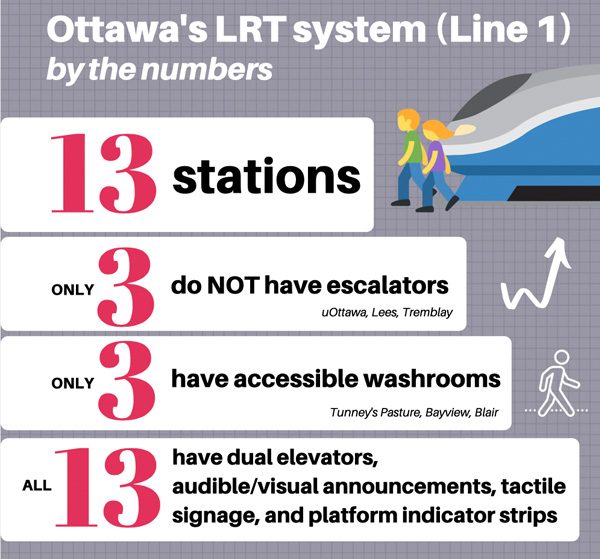

For instance, the accessible bathrooms, located in only three of the 13 stations, were confusing to use, said Morris. The lock button was too similar to a general help button. Many station maps also had small print with very low contrast, making them hard to read.

“They didn’t realize just how confusing it was to us until we all went in to try it,” said Morris. “It’s not just us that benefits, it’s in everybody’s best interest to ask.”

Morris’s colleague, Kim Kilpatrick, who is blind and uses a guide dog, also stressed the importance of a more inclusive design earlier in the process. She had several phone calls with RTG regarding accessibility services prior to the tour.

“We had been more hopeful that we would have been consulted more,” said Kilpatrick. “They didn’t ask us questions as they were building it.”

Keenan Wellar was never consulted before the walkthrough. “It’s off and on with the city,” said the co-director of LiveWorkPlay, a non-profit supporting people with intellectual disabilities and autism.

“If there was a prior call or offer to be involved in any of the design we sure didn’t see it or weren’t aware of it, and no one reached out to us about that,” said Wellar. “I don’t know if there’s a whole lot of things that can be changed once you’ve constructed a light rail system.”

Still, the group on the tour was impressed with several services, including loud announcements for upcoming stops, tactile signage including Braille, and new barriers between train cars to prevent slipping.

“When we got there, we thought it was really good, but there were a few little tweaks we suggested,” said Kilpatrick.

In particular, the invitees said tactile signs were well done, but they suggested that most people still need to learn what they actually mean. Tactile signs may have raised ridges that outline letters and images.

“I could just picture [people] standing in the middle of the station, like, spinning both ways going, ‘Okay which way?’ ” said Wellar. “It’s part of the ongoing challenge to have those sorts of needs included in accessibility considerations. It’s often focused on physical things.”

For the design team, “interpreting and reconciling … codes and standards relating to accessibility in the station designs” was indeed a problem, said Michael Morgan, director of Ottawa rail construction, in a statement to Capital Current. At least six codes had to be respected, said Morgan, including the Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act (AODA), and the Ontario Building Code. The OC Transpo website does offer an overview of the LRT’s accessibility features, and how to recognize and use them.

After their preview, Morris, Kilpatrick, and Wellar concluded that RTG had tried to anticipate the full gamut of disabilities, including mobility and intellectual.

“I didn’t get the feeling that they were leaving anybody out,” said Kilpatrick. “It felt like they really did care what we thought.”

Wellar said the stations’ flaws are minor and are “not going to be a crisis.

“They were taking notes and they seemed quite serious,” said Wellar. “Obviously they can’t change the physical environment now, but they can put up signage and things. They seemed to be quite interested.”

Very privileged to represent @LiveWorkPlay on an accessibility advance tour of @ottawacity @OC_Transpo Light Rail Transit! We promised not to share meaningful photos until Saturday but the big story is definitely going to be Pimisi station! #ottcity #ottnews #ottawalrt pic.twitter.com/vAJOQSGbO2

— Keenan Wellar 🐝 (@SocialKeenan) September 12, 2019

For others, it is still too early to make a final judgment about LRT’s accessibility. The major bus route changes on Oct. 6 are also expected to have an impact on commutes, said Rachel McKeen, communications co-ordinator for the Causeway Work Centre, in email correspondence with Capital Current. Causeway is a non-profit that works with individuals struggling with mental health disabilities.

“Ultimately, we feel that it’s too soon to properly get a sense of our clients’ perspective on the LRT system. Many of our staff have not had the opportunity to try out LRT,” said McKeen. “It will be very interesting to see how our clients’ commutes will change once the bus routes change.”

OC Transpo will continue to monitor Confederation Line’s accessibility services and receive feedback, said Pat Scrimgeour, director of customer systems and planning, in a written statement. Members of the public can submit feedback at the official OC Transpo website here.

Kathy Riley, accessible transit specialist for OC Transpo, was unavailable for comment on why local disability groups weren’t consulted earlier.