It was the year 1990, and at age eight, Shonna Foster was already decades ahead of her time when she starred in a short film written and directed by Black Canadian director, Annmarie Morais.

Titled Gone a Foreign, the film showcased Foster as the lead character playing a young girl who immigrated from Jamaica to live with her father, her white stepmom, and stepsister in Canada. With an interracial cast and a similarly diverse setting, Shonna found herself living an experience she could only sum up into one word — “magical.”

“I have a (sense of) nostalgia just thinking about that experience,” Foster said. “I remember as a child watching her work and thinking, ‘Wow… I want to do this’.”

Flash-forward 30 years, and Foster is a director and producer — but films led by Black, female directors remain almost as rare as they were decades ago.

When it comes to creative leadership roles, women have a long way to go in the film and television industry. The path is even longer for women of colour, according to a 2019 report by Women in View, an organization dedicated to strengthening gender diversity in Canadian media.

A long way to go

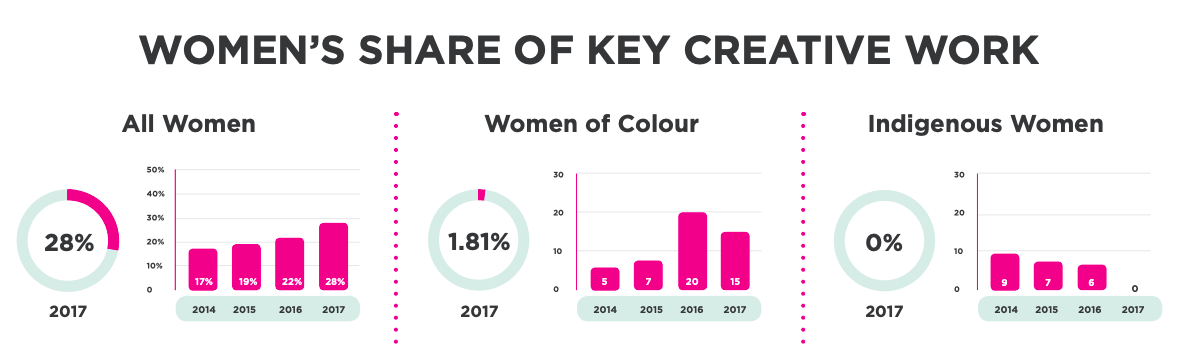

The report, which analyzed 5,000 national film and TV contracts between 2014 and 2017, covered creative leadership roles, including writing, directing, and cinematography, in productions funded publicly by Telefilm Canada and the Canadian Media Fund. The study found that only 28 per cent of those roles went to women over that period. In the same span, only 1.81 per cent were given to Black women and 0.69 per cent to Indigenous women. Of the 24 Canadian TV series created in 2017, not a single one had an Indigenous woman in a creative leadership role.

“The greatest barrier is history and that the culture was primarily created by males,” said Jan Miller, an international film and TV pitch expert who works on the board of directors at WIV, in a Zoom call from her Nova Scotia home.

“The business culture, the hiring culture — everything is very based on that sensibility. The biggest challenge for us is to break the historical pattern and shift that landscape.”

Miller said research by WIV has played a pivotal role in the progress women have made in film and TV since the group began issuing annual diversity and inclusion reports in 2012. The intent behind the reports was to provide concrete numbers so the problem could no longer be ignored.

“We were the first to collect statistics on diversity and inclusion and that had a huge impact on the conversation today. It really called out the broadcasters, so things started to shift,” she said. However, there is still a long way to go, she added: “There’s been some progress, but still no progress for women of colour or Indigenous women.”

In 2017, 14 per cent of the crew for male-led series were women and only two per cent were women of colour, the study found. By contrast, on female-led series, the number of women on the crew spiked up to 53 per cent. In the few instances where BIPOC women were in charge, eight per cent of creative roles went to Black women and 22 per cent to Indigenous women.

“Time and again, we’ve shown that women are just as capable as men — all genders are as capable as men — at holding these positions,” said Karen Bruce, executive director of Women in Film Toronto (WIFT), the Toronto branch of a global non-profit with 40 chapters worldwide dedicated to the development and advancement of women in the screen media industry. “But typically, men just hire other men.”

This trend isn’t exclusive to Canada. According to a 2017 report published by the Canadian Media Producers Association, studies from around the world have found a similar gender disparity in leadership roles for film and TV shows. After collecting data from 14 countries in the global North, including the U.K., France, and Australia, the study found women graduate from postsecondary studies in film and TV at equal rates to men, but rarely advance beyond 20 per cent of representation in decision-making and core creative roles.

A worldwide trend

Between 2012 and 2017, Canadian women made up 17 per cent of total feature film directors, ahead of the U.S.A. (13 per cent) and the U.K. (13.6 per cent). However, Canada was trailing many countries such as Ireland (20 per cent), France (22.6 per cent), and New Zealand (30 per cent). Sweden was leagues ahead of all other countries in the study, sitting at 50 per cent.

“When I started out, it was a very male-driven industry,” said Bruce. “There (weren’t) a lot of women to look up to in senior roles.”

Bruce’s organization has a mentorship program called WIFT Connect, which offers members with different levels of experience a series of one-on-one and group meetings over a six-month period through which they can learn from one another. This year, the group made a commitment that at least half of their mentees will come from BIPOC communities.

“The priority in our programming and our bursaries is BIPOC and underrepresented communities,” she said. “We just don’t always commit it will 100 per cent happen because we don’t always get applications from those individuals.”

This is a crucial point. Why aren’t underrepresented communities applying? Lisa Michelle Cornelius, co-chair of the diversity and inclusion committee at the Canadian performers’ union, ACTRA, said it’s because they are underrepresented.

“You have to see yourself in order to get involved,” she said. “Art reflects life and vice versa. If you don’t see yourself represented, especially as a young person coming up, it shapes the way you see yourself.”

As a Black actress, Cornelius knew she was a performer from a very young age but didn’t initially pursue a career in acting because “it didn’t seem like a viable career.” Instead, she chose to study advertising at Sheridan College before circling back to where she felt she belonged several years later. Now she has acting credits in Star Trek: Short Treks (2018) and Black Mirror (2011).

Cornelius described her brief experience playing a teacher on the set of Black Mirror as amazing, particularly because that episode was directed by the high profile American actor and director Jodie Foster.

“It was bananas,” Cornelius gushed. “I had a small role but when I got on set, she looked me in the eye and went, ‘Lisa Michelle, right?’ then said, ‘Hi, I’m Jodie’ as if I didn’t already know.”

Turned out, Foster had watched her full audition tape and wanted to compliment her on doing a great job. Before this, the most Cornelius had ever gotten from a director was passing acknowledgment.

“She came on set and she saw me, so I felt really valued in my small role,” Cornelius said. “This is just how women see other women.”

Diversity, onscreen and behind the camera, is important for aspiring actors, directors, and other key players in the industry. But research also shows it’s also increasingly important to audiences — especially young audiences, who will drive the future of the entertainment industry.

People of colour accounted for one-fifth of the Canadian population, and that number is expected to jump to one third by 2036, Statistics Canada reported in 2017.

However, those numbers are not being reflected in film and TV shows — and young people are noticing.

VICE Media, in partnership with Ontario Creates, a provincial agency committed to the economic development of the province’s creative industries, surveyed 500 Ontarians about viewing habits in August 2019.

Significantly, half of those surveyed said they believed the industry still hasn’t caught up in terms of representation, despite a demonstrated willingness to pursue unique cultural content. This is shown through their increased gravitation towards a variety of diverse creators on platforms such as Instagram and TikTok.

Seeing content that reflects the real world helps viewers understand the history and the humanity of people from other cultures, said Aisha Jamal, a film studies professor at Sheridan College.

“When you don’t represent that on screen, how are you supposed to understand your fellow human being who might come from a different cultural context?” she asked. “You’re missing a whole society — their stories and their perspective. We’re always saying movies create empathy, but if you’ve only seen people like yourself, you’ll never understand or feel for people who don’t look like you.”

The VICE report concluded more diverse representation is key to capturing the attention of young people, as well as a focus on global content and empowering unique voices across creative platforms.

Our goal is to level the playing field. This can only benefit the industry as a whole; increased competition can lead to better-quality projects that connect with audiences whose tastes and interests are changing along with the cultural landscape.

— Carolle Brabant, executive director, Telefilm

Canadian broadcasters and public funders have already begun the shift: in 2016, CBC announced a commitment to gender parity within scripted TV series. Women accounted for half or more of the directing roles in shows such as Murdoch Mysteries (season 10), Heartland (season 10), and This Life (season 2). This shift was reflected in the WIV report on diversity in leadership roles, which found that, between 2016 and 2017, the total number of female directors in Canadian film and TV productions grew 15 per cent.

The CMF and Telefilm have also taken a number of steps to improve diversity in their productions in recent years. In 2017, CMF announced a series of measures to increase the roles of women in CMF-funded productions. These included changes to its policies and guidelines, support for third-party initiatives, gender equality within juries evaluating creative projects, and more. Similarly, in 2016, Telefilm Canada revealed several measures to achieve gender parity in director, producer, and writer roles throughout their productions. In the following year, Telefilm made a specific commitment supporting Indigenous filmmakers by investing $4.7 million in 11 Indigenous productions.

“Our goal is to level the playing field,” said Telefilm’s executive director, Carolle Brabant, in a public statement. “This can only benefit the industry as a whole; increased competition can lead to better-quality projects that connect with audiences whose tastes and interests are changing along with the cultural landscape.”

Pushing for more diversity

Meanwhile, grassroots organizations are continuing push for more diversity in Canadian media. Among the biggest players is BIPOC TV & Film. Founded in 2012, the Toronto-based group is comprised of creatives from all walks of life who are dedicated to increasing diversity, both in front of and behind the camera. The group holds panel discussions, Q&A sessions, workshops, and a variety of networking events to help BIPOC secure jobs in the film and TV industry.

Shonna Foster is now part of this organization and is in charge of youth and emerging talent initiatives for the group. As someone who mentors young Canadians breaking into the industry, she is frustrated by the barriers that BIPOC and marginalized groups continue to face. However, she remains steadfast in her hope that more people will have the same life-changing opportunity she had as a child so long ago, when she stepped onto that first, special set.

“I want to see Black people, Indigenous people, People of Colour — especially women — at the head and heading studios,” she said. “I want to see a beautiful, eclectic array of stories told by individuals from those cultures and backgrounds. I want to see a table (of creators) that looks like the world.”