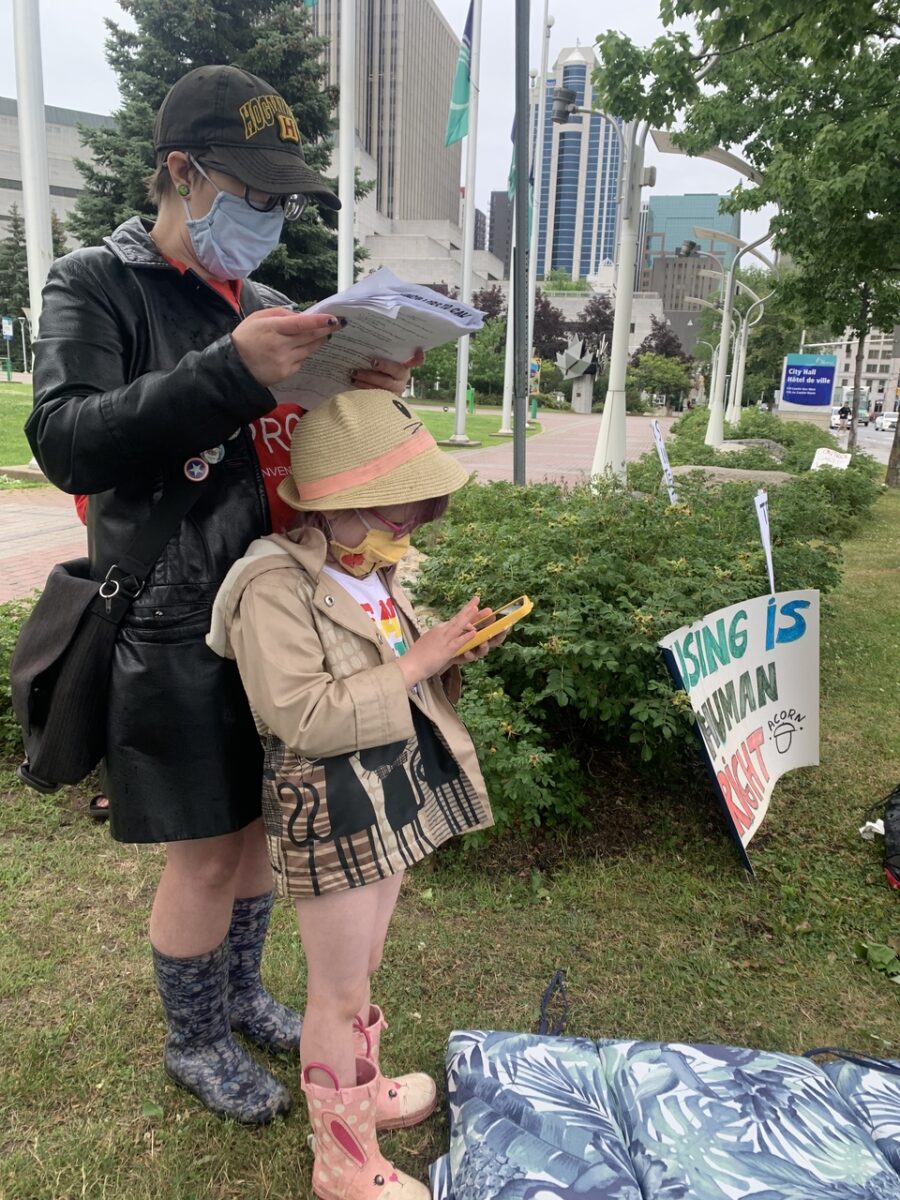

Ottawa City Hall was the site of a protestWednesday that urged the city to enact an anti-displacement policy to protect low-income tenants from eviction because of renovations in or demolitions of existing buildings.

Members of ACORN Ottawa also urged the city to require developers and landlords to compensate tenants when they are asked to move because of changes to the buildings in which they live. This would include finding temporary housing for displaced tenants or paying the difference between what tenants can afford and what’s available on the market. Tenants are also calling for rent stabilization.

[Photo @ Hana Sabah]

Ottawa has seen several high profile instances of tenants being displaced from once-affordable housing in recent years including from Heron Gate, Sandy Hill and now Manor Village in the city’s west end.

Renovations or demolitions can allow landlords to raise rents beyond the limit of 1.2 per cent set by the province, often pricing the homes beyond the ability of low-income tenants to pay.

As an example, protestors pointed to concerns that Smart Living Properties, which recently bought an estate in Manor Village, is converting two-to-four bedroom townhomes into student housing complexes which rent for $3,200 for a four to six-bedroom unit, well above what many residents say they could afford.

Smart Living Properties responded to the concerns in an email to Capital Current.

“We are renovating the Manor Village community right now. No one has been asked to leave, and we have offered an incentive of six months’ rent plus moving expenses. We’ll also help tenants find a new home, if they need it.”

The support will last until September, potentially leaving many tenants struggling to find affordable housing.

The expansion of the O-Train is also having an impact on “reno-victions” or “demo-evictions,” protesters say.

In November, the city purchased to demolish about 120 homes in Manor Village and Cheryl Gardens neighbourhoods, to allow the light rail line to extend to Barrhaven, potentially displacing hundreds of residents. This was after Ottawa became the first city in Canada to declare a housing and homelessness emergency.

Somerset Coun. Catherine McKenney and Kitchissippi Coun. Jeff Leiper, both spoke to the protesters. The two councillors represent wards where tenants have been affected by such reno- and demo-victions.

Leiper said, “the LRT is coming through, and increasingly, in the absence of policies that ensures that everyone can afford to live there. We’re putting huge investments in making places like Kitchissippi and Centretown and other great neighbourhoods better … but that investment is wasted if only the most affluent in our city can afford to live there.”

“We need a strong policy, an anti-displacement policy,” McKenney told Capital Current, “that ensures that when a developer comes to us and asks for permission to redevelop … part of the conditions put on them is that the tenants that are presently there are not displaced.”

Amanda Mcmahon says she’ll continue fighting to keep her home in Manor Village.

Maintaining community

“We don’t have anywhere to go,” she said. With four children, two dogs and her disabled mother living with her, Mcmahon is struggling to find a new home to house her family. Her current rent stands at $1,414 with utilities included and a backyard.

“Even a two-bedroom apartment right now is more than that,” she added.

For tenants like Mcmahon, it isn’t just about finding a new home, it’s also about maintaining the community that has welcomed her and her family.

Her son has anxiety and a speech impediment and Mcmahon credits her neighbours for taking care of him and for reserving judgment on his disabilities. Relocating would not just be about finding an affordable place to live, but also finding a similar welcoming community, she said.

“If you have an entire community that you displace and you are making profit from that, it is incumbent upon us as a city to ensure that part of that profit goes to ensuring that people are not displaced,” McKenney said.