A Carleton University alumnus and advisor to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission says he “never thought for a second” that Canada would formally devote a day to acknowledge and reflect on the dark legacy of the residential school system and the country’s history of colonization of Indigenous territory.

Canada’s first National Day for Truth and Reconciliation on Sept. 30, previously celebrated as “Orange Shirt Day,” commemorates the horrific legacy of residential schools and honours their victims and survivors.

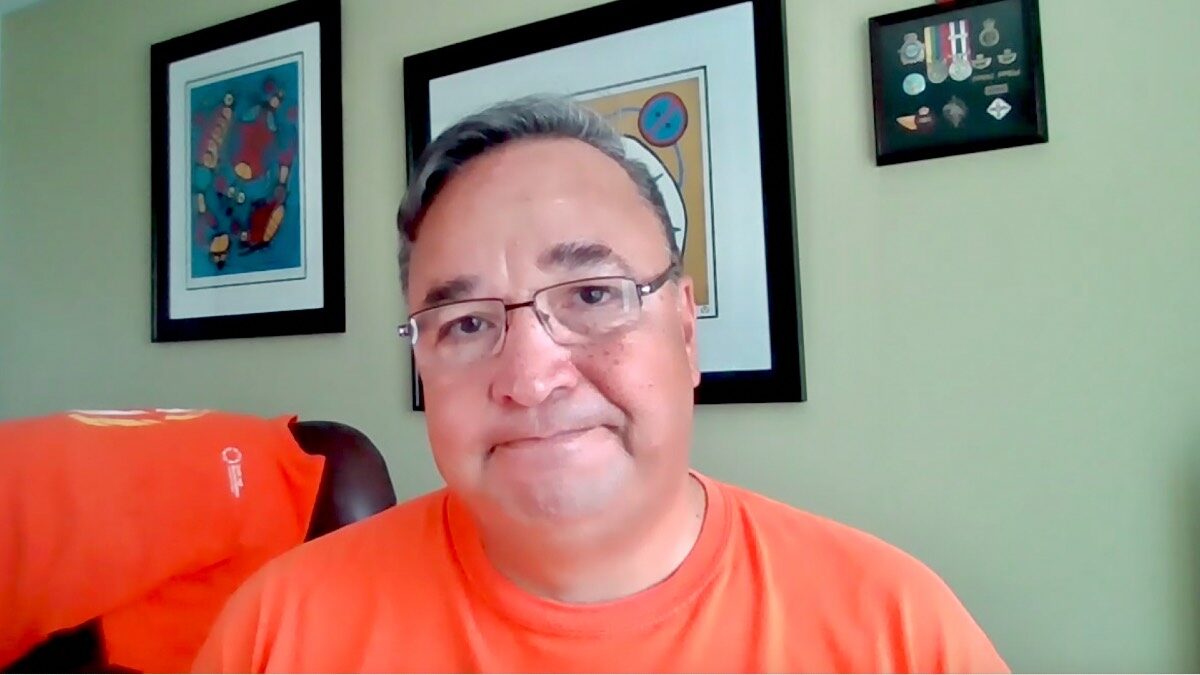

Alongside demonstrations, marches, vigils and speeches across the country, Carleton University’s School of Public Policy and Administration welcomed Carleton graduate Tim O’Loan to speak about reconciliation during a Zoom webinar.

“One of the things that we heard at the TRC was that people were shocked. They had their whole schooling in this country, including graduate school and such, and they just never heard a thing about residential schools or its legacy.”

Tim O’Loan, Carleton alumnus and advisor to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission

O’Loan, a member of the Dene Nation, graduated with a B.A. in political science from Carleton after serving 10 years in the Canadian military.

Along with his role as negotiator and intergovernmental relations analyst for the government of the Northwest Territories, O’Loan completed his master’s degree in Canadian Studies before joining the TRC in 2010 as an advisor to commission chair Justice Murray Sinclair.

In his talk, “Planting a Seed Towards Reconciliation,” O’Loan said that part of what makes this day “so special” is that a statutory holiday, given royal ascent in June 2021, was one of the TRC’s 94 calls to action.

“I never thought for a second that this would be a federal holiday,” said O’Loan. “But here we are. I’m very honoured to be given the space, because I get to heal. I hope survivors on this day, as a result of this day, will get to heal.”

O’Loan said that as much as the holiday should be about listening and learning from communities, survivors and victims’ families, it is important to understand the overwhelming trauma that accompanies enduring memories of loss, abuse and tragedy.

“It’s not a good memory,” said O’Loan, comparing Sept. 30 to the way “some veterans won’t get out of their basement to celebrate Remembrance Day.

He added: “There’s no wonder there’s so much trauma in the communities. These ‘secrets’ … they were always known … (but) there was never anyone that was there to receive their truth.”

This is part of why O’Loan’s presentation centred around his work as a public speaker and an educator on the subject.

He noted how he now feels comfortable sharing some of his personal life stories, a PTSD diagnosis and his struggles in an effort to normalize these challenges and place importance on mental health.

As a child adopted into a non-Indigenous family because his mother was dealing with the trauma of her residential school experience, O’Loan said he also struggled with his identity as an adult.

“I’ve always felt offside, to be honest, and not belonging,” said O’Loan. “I didn’t realize that I didn’t really know who I was … (But) I’m one of many Indigenous peoples living with the principle that we just need to know where we come from. And in my 20s, when I was in the military, those lights were going on (inside me) and as an Indigenous person I was just trying to find myself.”

Although “finding himself” and his voice took some time for O’Loan, 55, he said he benefited greatly in being able to share his work with the Indigenous and non-Indigenous community.

Ultimately, education and understanding is a common thread in reconciliation, O’Loan noted at the end of the talk. He said that’s something Indigenous-led organizations are trying to highlight given that over the past 20 years it has not always been a priority in the Canadian school system.

“One of the things that we heard at the TRC was that people were shocked. They had their whole schooling in this country, including graduate school and such, and they just never heard a thing about residential schools or its legacy,” said O’Loan. “And that’s what I refer to as our quiet, empty chapter in our history books. And we have come a fair distance, but we really have a lot farther to go.”