As COVID-19 restrictions continue, ‘normal’ vehicle traffic flows have been turned upside down, with significant drops reported in collisions but also in use of public transit.

According to a recent report from the International Transport Forum, road deaths in Canada were 34 per cent lower in April 2020, the month after the pandemic was declared, compared to April 2019.

Insp. Dave Tovell, regional traffic and marine manager for the Ontario Provincial Police’s East Region, says reduced collisions are evident across the province.

“As of March this year, we saw a quick decrease in the number of collisions all throughout the province,” said Tovell. “We attribute it to the lower traffic volumes.”

While the number of fatal collisions in Ontario was down slightly between January and September this year compared with the same period last year, the total number of collisions was down nearly 30 per cent.

According to Tovell, the reduced number of commercial vehicles on the main highways has played a major role in the decrease.

“A lot of our collisions on the 400-series highways are influenced by the actions of our large transport trucks,” he said.

But this doesn't mean Ontario's roads are 'safer'. For one thing, Tovell says the OPP has seen more instances of dangerous driving.

“We have a lot more stunt driving charges than we normally have,” said Tovell. “Highways are wide-open for vehicles to get their speeds up to 150 and feel safe because there’s no other vehicles around them.”

Drinking and driving

Dr. Evelyn Vingilis, a professor in the department of epidemiology and biostatistics at Western University, says factors like economic stress, increased alcohol consumption, drug use and pandemic anxiety could influence individual drivers and make roads less safe.

“Some commuters might engage in speeding that could increase collision risk. Others may be driving normally,” said Vingilis, whose recent work analyzes the potential effects COVID-19 could have on road safety.

“We need to monitor what patterns and trends we are seeing by jurisdiction and driver group, over the different waves and control policies of the pandemic.”

Tovell said he has noticed an increase in impaired drivers since the start of the pandemic. He said he believes this may stem from changing habits, perhaps including more people drinking during the day.

“We are finding, mostly through our observations from report-backs on the number of roadside screening checks, that more people are driving under the influence of drugs or alcohol,” said Tovell.

Public transit use

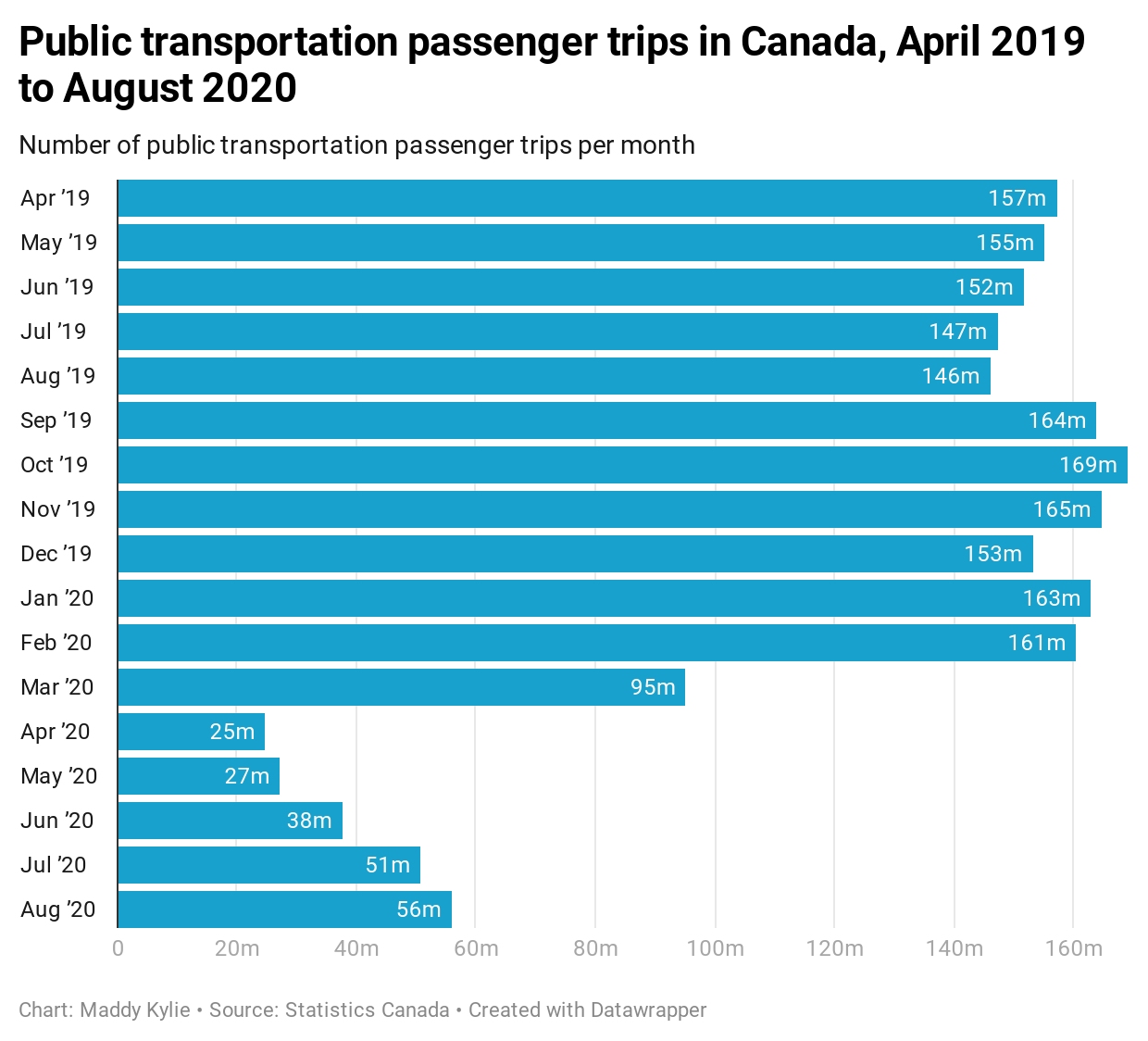

The pandemic has also caused a significant decrease in the use of public transit. According to Statistics Canada data, ridership in June 2020 was 75 per cent lower across Canada compared to June 2019.

This will leave many municipalities with significant transit revenue shortfalls. According to the City of Ottawa, additional costs related to COVID-19 include $12.8 million for increased cleaning and between $50 and $60 million from lower ridership and fares. (On Nov. 18 the city's transit commission approved a fare increase beginning Jan. 1, 2021.)

But for some, public transit remains essential, despite COVID-19 concerns.

Before the pandemic, Jacob Lindblad, 21, commuted by bus. He was able to work from home in the spring and summer but is now working in an office again.

“I mean I would be more comfortable driving to work," he said.

"The bus still feels risky, but I don’t have a car. So, the bus is really my only option.”

Lindblad's commute to downtown Ottawa is just over an hour long. He says he has noticed the bus is a little less busy now. However, he says his trip is just as long as it was before the pandemic despite the reduction in passengers.

Once the pandemic is in the rear-view mirror, it's not clear whether traffic and transit patterns will return to pre-COVID-19 levels. Some businesses, including Shopify, have announced that their staff will continue to work from home as much as possible. It may take a long time to find the new normal for traffic and transit flows.