On June 15, Cihan Erdal was released from prison in Ankara, Turkey. The Carleton University student had been in prison nearly nine months. Since his release, he’s attended hearings and reported twice a week to the Turkish police. He can’t leave the country and return home to his spouse, Ömer Ongun, in Ottawa.

In solitary, his tiny room had a bed, a small kitchen and a table. Food, clothing and other basics were inconsistent and insufficient. For 25 days, Erdal spent almost every hour in the room and did not see or speak to another individual, including the 80 people arrested at the same time. He had no connection to the outside, he told Capital Current over Zoom.

“You feel as if you are guilty,” says Erdal. “You were kept in a horrible place that no human being deserves to stay in.”

Erdal, 32, was born on the west coast of Turkey where his family harvested olive trees. He moved to Ottawa in 2017 to further his studies and became a permanent resident. In August 2020, Erdal and Ongun went to Turkey to visit family. Erdal also was doing research on his PhD thesis. Ongun returned to Ottawa after two weeks, but Sept. 25, 2020, Erdal was detained.

For 36 hours, no one heard from him.

“It was more than a day,” Ongun said in the joint interview. “We didn’t specifically know where Cihan was and what the conditions were.”

Erdal has been charged with inciting violence in relation to protests in October 2014. The evidence was two social media posts that were “seen by Turkish authorities as an incitement of violence,” says Erdal.

He is part of a crackdown known as the “Kobane Case” which detained more than 80.

Protestors called on the Turkish government to intervene to help Syrian Kurds who were being attacked by the ISIS terror group in the Kobane region near the border with Turkey.

Erdal was then affiliated with the People’s Democratic Party of Turkey, who helped organize the protests. He says he was not involved in the organization of the demonstrations.

“The official indictments released in January 2021 accused me and other activists of encouraging the common protests of 2014 when thousands took to the streets in the southeastern Turkey to protest against Ankara’s inaction in protecting Syrian Kurds against ISIS,” says Erdal.

“It took a while for the government, or especially Global Affairs, to respond. For a few months, they just sent standard text responses to our inquiries.”

Ömer Ongun, spouse of detained Carleton PhD student Cihan Erdal

After the protests, Erdal was asked to give a statement to the Turkish authorities. At the end of 2015, he did. No legal action was taken against him then. And he has been back to Turkey several times to visit family and do research.

Both Ongun and Erdal say that they weren’t worried about going to Turkey in 2020.

“There was an investigation, which was still open, but I had given my statement in 2015,” Erdal said. “At that point, I hadn’t experienced any action. We both did not see any risk to visit our parents.”

For the first 25 days off Erdal’s confinement, community members, friends and family met daily to try and find where he had been taken.

“There are certain things you have to do very urgently, getting some clothes to him, making sure he has food or making sure that he doesn’t receive any physical torture,” says Ongun.

Ongun and others pushed the government to move all the Kobane Case prisoners out of solitary. Eventually, they were transferred to a maximum security F-type prison in Ankara. F-type prisons hold, among others, political prisoners, members of armed organizations and organized criminals. A 2001 report by Amnesty International has raised concerns about these prisons.

In his new jail, Erdal was kept with two other Kobane Case prisoners.

“The second place they took us was more institutionalized,” says Erdal. “It was also like a school. I mean, the corridors, the avenues, the architecture of the prison was like a school. As if you were someone to be educated, someone to be corrected, to be fixed.

“We were far from the city centre. It was also giving you the feeling of being very alone,” says Erdal. “You are not only far from your loved ones, but also from the world physically.”

Meanwhile Ongun was organizing letter writing campaigns, petitions and pushingd every day for Erdal’s release. He began by reaching out to the Canadian government.

“One of the first reactions that we received from the Canadian government was ‘Oh, he’s not a citizen,’” says Ongun. He was told the government was “monitoring” the situation.

Erdal is a Turkish citizen and a permanent resident in Canada.

“It took a while for the government, or especially Global Affairs, to respond,” says Ongun. “For a few months, they just sent standard text responses to our inquiries.”

He says that the past few months have been much better.

“We started meeting regularly with Global Affairs Canada and the parliamentary secretary of foreign affairs, the Canadian embassy, the consular affairs, they appointed a person and official in Ankara who are lawyers in Turkey and started having regular contact and communication,” says Ongun.

When asked what Global Affairs has been doing since his release, they did not comment.

“Global Affairs Canada is aware of the release of a Canadian permanent resident in Turkey,” the department said in a statement. “The government of Canada does not comment on matters before the courts. In the interest of the well-being and privacy of the individual, we will not be providing further details at this time.”

But other Canadians and people from around the world have expressed their support for Erdal through letters.

“There were lots and lots of letters,” says Erdal. “I had to reply, and I replied to them all.”

Ongun and Erdal both say the support was invaluable.

Letters weren’t the only thing Erdal wrote while behind bars. He continued to work on his doctorate which “focuses on the experiences of young people who were engaged in activism for radical social change in Europe and primarily the inner cities of Athens, Istanbul and Paris.”

He had completed eight of the 20 interviews he had planned for during his trip. At the beginning of his imprisonment, he was denied access to his research materials.

“Lawyers went and protested this and then Cihan was given access to all the school materials,” says Ongun.

When he was granted access, Carleton University sent a package of material.

Erdal worked through his former research supervisor in Turkey, Derya Firat, to continue the interviews. She connected him with research subjects and Erdal prepared the questions and sent them to her, while friends transcribed the interviews.

“I don’t think I’m exaggerating to say that the process of writing this article behind bars has turned into coalition building,” says Erdal.

The research he conducted from his cell will fill a chapter in a book on young people, radical democracy and community building that is to be released next year.

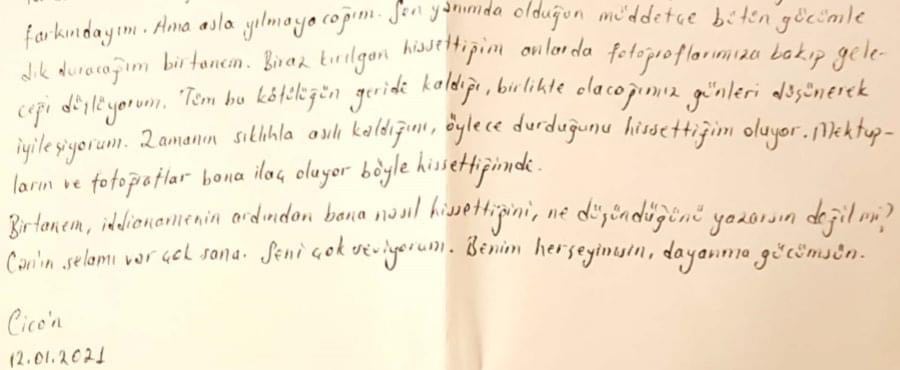

“I don’t want to get emotional, but I discovered the importance of letters, started to approach them as valuable materials, instruments or new literary texts to build our communication relationship.”

Cihan Erdal, Carleton University PhD student detained in Turkey

Erdal says he will do his best to continue his research from Turkey until he can come home to Ottawa, with the support of his current supervisor, Jaqueline Kennelly.

“I had the chance to talk to my doctoral supervisor this week. We both agreed to continue my research from Istanbul, at least for now,” says Erdal

His contact with friends was done through letters. Other than just his immediate family, Erdal was not allowed to communicate directly with anyone outside. And, because same-sex marriage is not legal in Turkey, Erdal and Ongun’s union is not recognized.

“Every Sunday night, both of us would write letters to each other,” says Ongun.

Erdal held back tears when asked about the letters.

“I don’t want to get emotional,” Erdal says. “But talking about this disconnection of us in my imprisonment, I discovered the importance of letters, started to approach them as valuable materials, instruments or new literary texts to build our communication relationship.”

But at the time of Erdal’s arrest, Ongun and Erdal had not been very public about their 10-year-long relationship.

“We lived in this bubble,” says Ongun.

Erdal was an openly gay, but Ongun was not. When he started advocating publicly for Erdal’s release, he decided to come out, despite the potential consequences.

“We were concerned because, what if some guard or some officer lurking there decides one night and just goes in and tortures him or does something to him,” says Ongun.

Erdal wrote to the prison officials demanding that Ongun be put on the list of his immediate contacts.

“While I was writing that letter, I was thinking of potential risks that I would be exposed to,” says Erdal.

While Ongun never did make the list, they both thought that progress is being made.

“That was going to be a big win for the queer community in Turkey,” says Ongun.

While Erdal did not experience torture, he says he believes the possibility was always there.

“I have heard that the people who are still arrested, who are still detained, experienced physical torture during the trials this week,” says Erdal. “So, I mean, we always felt the possibility of such behaviours.”

Erdal defended himself at a hearing on June 15. In a surprise decision, he was conditionally released that same day. The trial will continue in September. Until then, he has to meet various conditions in his release.

“I’m not allowed to leave Turkey. And I have to report to the police state twice a week, which is still sort of an open-air prison experience,” says Erdal.

Being released doesn’t necessarily mean he won’t be sentenced.

“I can be sentenced to something which may correspond to the time I spent in prison, or we may face an adverse scenario that may require to spend much more time in prison,” says Erdal.

“These cases are used as ways to punish opponents who stand against the current populist discourse,” says Ongun.

“It’s turned into a trend to accuse people of being a member of a terrorist organization or supporting terrorism only because people have defended democracy,” says Erdal.

While Erdal was an activist, today he has turned to academia.

“Turkey is my home. I have emotional connections; I have an academic connection to this landscape,” says Erdal. “And I will still continue producing academic work in relation to Turkey and Turkey’s contemporary conditions.”

“Turkey is my home. I have emotional connections; I have an academic connection to this landscape. And I will still continue producing academic work in relation to Turkey and Turkey’s contemporary conditions.”

Cihan Erdal

Ongun says that it should be the responsibility of Canadian universities to help protect people like Erdal.

“How will Canadian universities and Canada itself as a country provide safety and security for those international global researchers who may be scholars at risk where they come from?” Ongun asks.

Ongun is hoping Canada will help him get back as soon as possible.

“Now it’s time for Canada to step up the game and say, ‘we want him home,’” says Ongun.

“It’s really hard to estimate (when) I can come back to Ottawa,” says Erdal. “I’m hoping as soon as possible to continue my academic research from Ottawa.”

With the help of their Ottawa-based human rights lawyer, Paul Champ, they have submitted an application to the United Nations’ working group on arbitrary detention.

“We reported everything to the United Nations Working Group on Arbitrary Detention. All these things like being put in solitary confinement, not having access to certain things or not being able to speak with me,” says Ongun.

“That’s what we are doing, checking in with friends and making plans, dreaming together about the next week or the next few months.”

Ömer Ongun

When asked how he feels now, Erdal says he’s “conditionally happy and conditionally safe.”

“I’m happy to see Ömer, to see my parents. I don’t have words to describe how I feel at the moment,” says Erdal.

For now, talking over the internet and advocating for Erdal’s Canadian citizenship is their new reality.

“That’s what we are doing, checking in with friends and making plans, dreaming together about the next week or the next few months,” says Ongun.

But Erdal says he has no regrets.

“I have never felt guilty for going back to my country. I shouldn’t feel guilty,” says Erdal. “The ones who must feel guilty are the politicians who created this atmosphere of fear for years, for academics, for opposition, for activists, for everyone advocating for human rights.”