Alicia Keys’ Girl on Fire echoed in the SPU Amphitheatre at St. Paul University in Ottawa on March 30. About a dozen people were gathered in the plush seats, chatting lightly as songs by women (for women) played in the background.

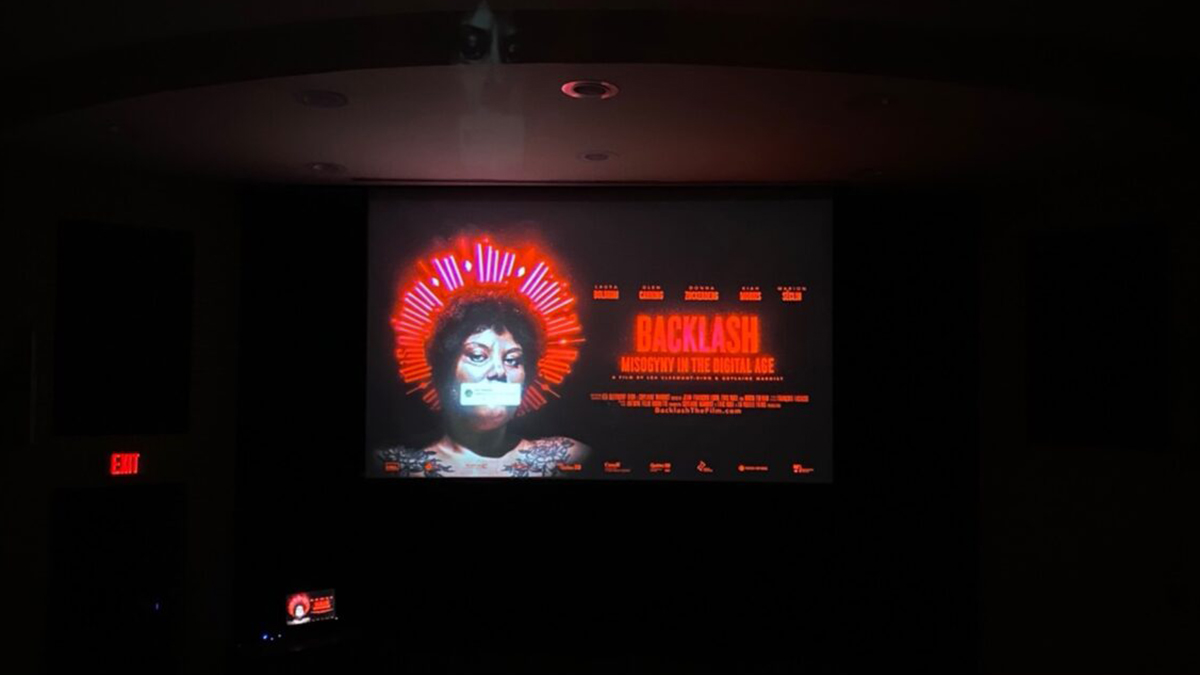

Dr. Krys Maki took the stage, introducing themself, gave a land acknowledgement and a content warning. The lights dimmed and Backlash: Misogyny in the Digital Age rolled onto the big screen.

The 2022 feature-length documentary film was directed by Léa Clermont-Dion and Guylaine Maroist and produced by Montréal-based La Ruelle films. The documentary, available on CBC Gem, centres on four women: Marion Séclin, a French actress and feminist YouTuber; Kiah Morris, a former Democratic representative of Vermont; Laura Boldrini, former president of the Italian Parliament; and Laurence Gratton, a Québec teacher. All of these women have been targets of online vitriol, their lives turned upside down by violent online harassment campaigns.

Unfortunately, this is a common experience for many women.

Data from Statistics Canada shows police-reported cybercrime increased from 17,887 instances in 2015 to 70,288 in 2021. The RCMP breaks down cybercrime into “technology as instrument” and “technology as target,” with cyberbullying falling into the “technology as instrument” category which also includes identity theft and child sexual exploitation.

Cyber misogyny seems to be on the rise as technology continues to permeate in most social spaces. According to the Canadian Women’s Foundation, “[w]hile people of all genders experience cyberviolence, women and girls are at greater risk of experiencing violence online, especially severe types of harassment and sexualized abuse.”

The intersection between bully and gender is learned from childhood explains Dr. Elizabeth Englander, a psychology professor from Bridgewater University.

“Children tend to adhere to rigid conceptualizations of gender as part of their efforts to understand the world around them,” she says. “As they grow, these conceptualizations become more nuanced and complex. Cyberbullying is the same as many other interactions between children in this regard.”

The film shows the this is not simply a Canadian problem. For example, United Nations Women reported one in 10 women in the European Union experienced cyber-harassment since the age of 15, with the highest risk for those 18-29 years.

“The increasing reach of the internet, the rapid spread of mobile information, and the widespread use of social media, especially since the onset of the COVID-19, and coupled with existing prevalence of violence against women and girls, have most likely further impacted the prevalence rates of [information and communications technology]-facilitated [violence against women and girls],” according to UN Women.

Diana Official hosted the Backlash screening. She says she recognized the emerging trend of gendered cyberviolence and decided she wanted to create a safe space for women to come together to discuss their experiences with gender-based violence.

The screening featured a round-table discussion with community experts such as Edeltraud Neal, president of the Provincial Council of Women of Ontario, Kathryn Ann Hill, executive director of MediaSmarts, Constance (Connie) Crompton, Canada Research Chair in Digital Humanities and director of the Humanities Data Lab, and Carolanne Victoria Tomsine, a Masters candidate in psychotherapy, counselling and spirituality at St. Paul University.

“Despite our differences, in terms of culture, in terms of age, we all have the same issues,” said Official. “So many women have experienced gender-based violence throughout their life, so the goal was to pretty much create a space where people had the opportunity to simply share their own experience.”

Official, a fourth year student of social communications at St. Paul University, says the reason she chose to screen Backlash was because of how intentional she felt the film was. She also wanted to highlight the issue of cyber misogyny, which she believes is not talked about enough in Ottawa.

“I know that it would have evoked emotions from the audience…what compelled me to actually screen this documentary was to have the opportunity to address cyber misogyny…because it affects everyone, the fact that the anonymous culture makes it easily accessible for bullies to simply target their victims,” said Official.

Official says that there are no policies or regulations that address this issue specifically enough. With misogyny present in many different fields, such as sports and gaming, the growing online aspect is cause for concern.

“People are desensitized to the point that we are normalizing, accepting and tolerating crimes against women, just for the sake of likes. And knowing that you’re not going to be reprimanded for what you’ve done,” said Official. “Because at the end of the day, the online space is so open and free.”

Researchers and others fear that the abuse will silence women’s voices online, particularly racialized voices. One recent study found that women who are targeted are more likely than men to become more cautious in expressing their opinions publicly, which may discourage women from entering public-facing professions such as politics or journalism. Some female political figures have publicly condemned the online hate they have experienced and some female journalists in Canada have long publicized the types of vitriol and abuse they receive regularly.

During his remarks at the annual Kesterton Lecture, hosted by Carleton University’s School of Journalism and Communication, Toronto Star owner Jordan Bitove addressed the prevalence of cyber harassment in newsrooms.

“I worry about our interns [and] our team,” said Bitove. To insure that they are protected, the Star is “asking law enforcement to be involved,” and “…[the] government to put policy and legislation in place to protect them.”

Increasing education, says Official, is the next big step in fighting this emerging violent misogynistic culture. She believes that facilitating a space for all genders, all races, all religions, all classes, all ages, to gather and discuss these issues is necessary.

Englander states that children and teenagers need to be taught the “importance of using technology in a way that is healthy for the user’s mental health, and healthy for their interpersonal relationships.”

“This includes teaching…about issues like how technology changes communications and emotions,” she says.

Official believes that by focusing on the intersectionality of the Ottawa community and placing importance in understanding that people experience persecution and violence in different ways, it will strengthen the fight against cyber violence.

If you or anyone you know has experienced or is experiencing cyberviolence, visit techwithoutviolence.ca for Ottawa-based resources. If you are in need of immediate services, call 9-1-1.