As vaccination rates rise, people have begun to return to the things they’ve missed including restaurants which are bustling with folks wanting to treat themselves to a meal out.

But the return of revenue to the restaurant industry is not necessarily being greeted with a return of eager staff.

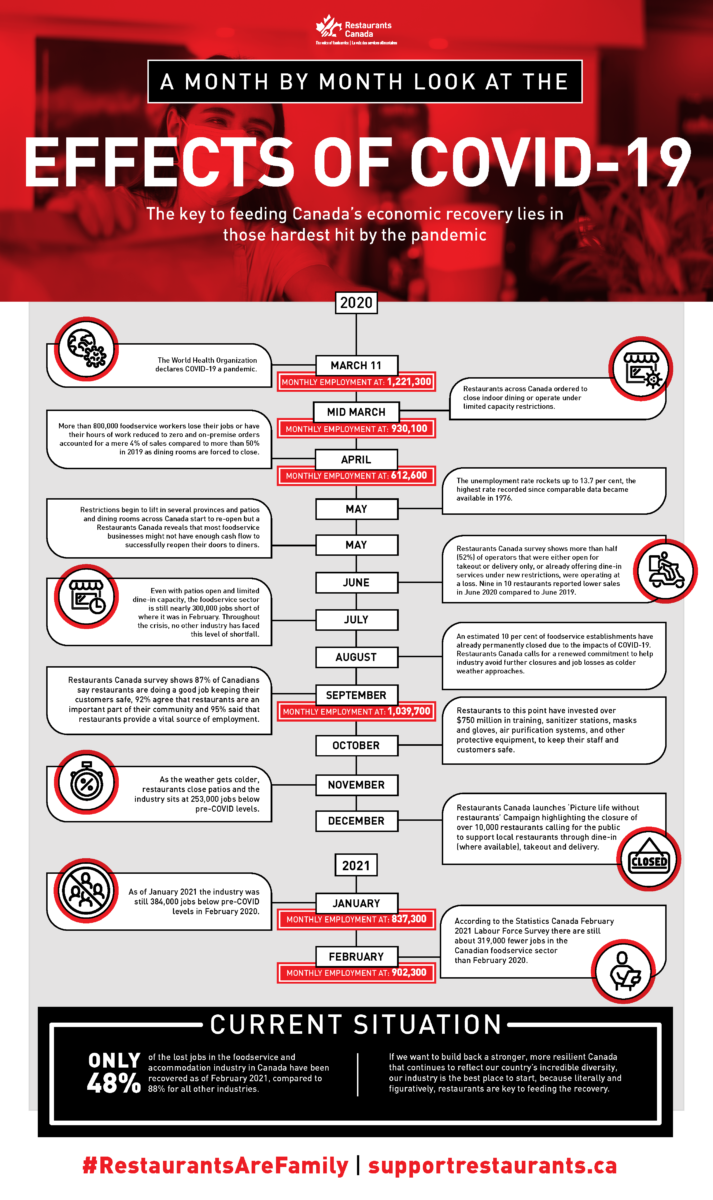

The food service industry has been one of the hardest hit by the COVID-19 pandemic. According to the Statistics Canada May 2021 Labour Force Survey, it accounted for almost two-thirds of the overall employment decline after February 2020.

But even as residents slowly reincorporate pre-pandemic activities back into their daily routines, the industry remains in a rut. The same survey shows that as of May 2021, there were still 364,000 fewer employees in accommodations and food services compared to pre-pandemic numbers.

According to Restaurant Canada’s latest Restaurant Outlook Survey conducted in July, 80 per cent of restaurants surveyed said they were struggling to hire back-of-house staff – chefs, line cooks and dishwashers – and 67 per cent said they were struggling to hire front-of-house staff – servers, bussers and hosts.

This has led to a concern that “nobody wants to work,” narrative, that supports such as the Canada Recovery Benefit (CRB) have enticed employees out of the industry.

But restaurant workers see it much differently. They tell of ridiculously long work hours, labour law violations and, sometimes, verbal and physical abuse.

I have worked in three different restaurants. Two were front-of-house positions and one was back-of-house. Two were pre-pandemic and one was during COVID-19. Two I walked out on and one I stayed. All three were not great work environments.

I stayed with my first job in the food services industry until my position ended at the end of the summer. I was a dishwasher and line cook at a private country club. Personally, I didn’t have much to complain about here, but I watched other workers experience much misery.

One example may offer an idea.

At the beginning of the summer, the chef hired a new pastry cook. She was the only one working in pastry. After a few weeks, she was tired of working long hours every day. One night for a big event, she worked until 2 a.m. The chef demanded that she be at work at 7 a.m. the next day. She never returned.

Part of the problem is that employees do not know their rights.

According to the Ontario Employment Standards Act, eight hours is required between each shift unless the number of hours worked is less than 13.

Furthermore, an electronic or written agreement is needed for an employee to work more than eight hours per day or the length of a regular workday, and for an employee to work more than 48 hours per week.

Many employers hide this regulation within a new hiring package and employees sign on without realizing that the stipulation even exists.

Sometimes being overworked isn’t the biggest problem. Food service workers may also experience verbal and physical abuse.

My second job lasted just less than two months. I worked as a server in Ottawa. Immediately after being hired, I sensed something wrong with the workplace environment.

I was warned about the head chef in the kitchen who was known to make rude or sexual remarks to the servers. I was also told by my female manager to just ignore him. Not much was done to make the problem go away.

The same manager who warned us about the chef would hit us. Not hard and not aggressively, but she would still lay a hand on us without consent.

But there was one incident that made me decide on the spot I would not return to work.

It was a Friday night and I was supposed to work the Saturday morning. It was supposed to be busy and we were already understaffed. That night I had an unexpected allergic reaction and my roommate took me to the hospital. I informed my manager to let her know that I would keep her updated but I probably would not be able to come in the next morning.

It turned out we were at the hospital until 6 a.m. This is the same time Cora’s opened. I called my manager again and told her that I had just left the hospital. She reassured me that everything was okay and that I did not need to worry about coming in.

I went home and slept for most of the day. When I woke up late in the afternoon, I had seven missed calls. I then received a text from the owner — “You better be at work tomorrow.”

I was being reprimanded. I was being reprimanded for missing work because of a medical emergency. I decided that I would not work in a place that did not care about me as a person. I went to work the next day and at the end of my shift, I never returned.

I also walked out on my third food service job but I lasted four years before I reached my limit.

I started working as a junior server/busser and eventually became a server at a four-diamond restaurant at an upscale inn outside of Toronto. The job seemed perfect for a university student trying to earn some extra cash. And to be honest, I loved the majority of my time there. But that is not to say it didn’t have its own issues.

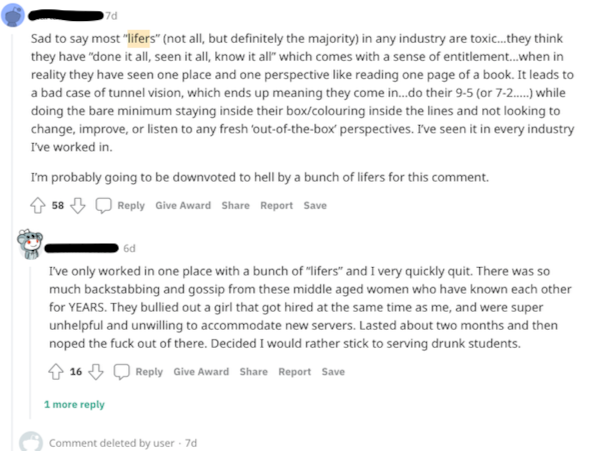

It was here that I was introduced to the concept of “lifers.”

A “lifer” is known in the food service industry as someone who has worked at a place for so long that they could do any position, but they choose not to. They are experienced enough to be a manager but claim they make more money as a server. They then complain about decisions made by supervisors.

There were a few “lifers” at this restaurant but there was one who made our lives particularly miserable. Everything had to be done her way. We were constantly told to redo things or retaught things that we did on a daily basis. She could also be verbally and sometimes even physically abusive.

But the problem was larger than the things she said and did. The problem was that the supervisors did not deal with her behaviour, claiming it was “just the way she was.” Regardless, even if a manager did confront her, she had been there so long, she often went over their heads.

There was also a constant tension between the kitchen staff and service staff. Kitchen staff would complain we were receiving tips of which they did not get a part. It’s usually customary for front-of-staff to give a small portion of their tips to the back-of-house staff.

Yet, the servers were the face of any mistake that happened in the front of the house or the back of the house — which led to a constant lack of teamwork leading to a downward spiral.

Then COVID-19 hit.

Summer 2020 was okay. While we were a little short-staffed, most workers had returned. It was 2021 where everything went up in the air.

I had actually quit this job back in August 2020 but hearing about the shortage of staff I returned this past June. For the first little while, iI and one other day server were the only ones working full time.

It was hectic, to say the least.

Being short-staffed affected the manager’s ability to make up a work schedule and it was taxing on us. It affected our service which in turn meant we made less money in tips. When a server is overworked, they often cannot provide the quality of service to which guests are accustomed. This often leads to a lower tip and thus less income for the server.

But it wasn’t just being short-staffed that drove me out of the restaurant. This summer the work environment became increasingly toxic.

The majority of people I was working with were white, middle to upper class, and rural dwellers. And a vast majority of them did not believe in COVID-19 vaccines. While there will always be people who choose not to get vaccinated, the people in my workplace were proudly unvaccinated and were constantly spreading misinformation.

One server even called a cook “stupid” for getting vaccinated.

After four years everything built up and I was ready to quit. After one particularly stressful morning at work, I walked out.

I understand that walking out on my job might not have been the best decision. But as a bottom-line worker, it was a way for me to make a statement. It was a way for me to say, not just in my words but in my actions, that I deserved to be treated better.

It is disappointing because there are a lot of positives to working in the food service industry. The people you meet and the skills you build will be with you forever. But for me, after three experiences, I do not plan to return to the industry.

With many others in the same position, it is no wonder there is a labour shortage.

Rebecca Gordon, a member of the Canadian Restaurant Workers Coalition summed it up well when she was quoted in Now Toronto saying: “Rather than framing it as a labour shortage issue, [I’d say] it’s really just a shortage of restaurants that provide decent work; restaurants that are respectful and value workers as humans.”